As Marc Jacobs paid homage to hip-hop in his A/W17 show, we take an opportunity to salute the woman who paved the way for the movement as we know it today

Last season, alongside an outpouring of praise, Marc Jacobs came under fire for his S/S17 show, in which a cast of predominantly white models were seen sporting multi-coloured dreadlocks piled atop their heads. The Insta-finger of cultural appropriation was immediately pointed at the designer and, whether you agree with these accusations or not, this season Jacobs has sensitively gestured toward making amends for whatever offence he might have caused previously. For his latest A/W17 collection paid homage to hip-hop culture and – rather than a misappropriation – it was undoubtedly a homage, with models of colour ranging from Slick Woods, Lineisy Montero and Grace Bol sporting ensembles that shrewdly referenced the fledgling moments of an era and the individuals who altered the course of musical history.

It was, in fact, the Netflix documentary Hip-Hop Evolution, which Jacobs cited as his main source of inspiration for a collection that felt truly diverse and refreshing: “The four-part series chronicles the poignant and pivotal cultural movement that reshaped and redefined the landscape of music, which gave way to a whole new language of style,” he said in his show notes. Featured in the documentary are the usual (and, it should be said, mostly male) kings of the genre, from Ice Cube to Afrika Bambaataa. Inexplicably, their female and equally as pioneering counterparts – the likes of McLyte and Salt ‘N’ Pepa – are left out of the documentary, with one exception: the ‘mother of hip-hop’, producer, musician and CEO of Sugar Hill Records, Sylvia Robinson. In light of Jacobs’ tribute – to both her headwear and her musical prowess – we take this moment to chronicle the life of Robinson ourselves, a woman who rouses much inspiration for both her strength of character and style alike.

Defining Features

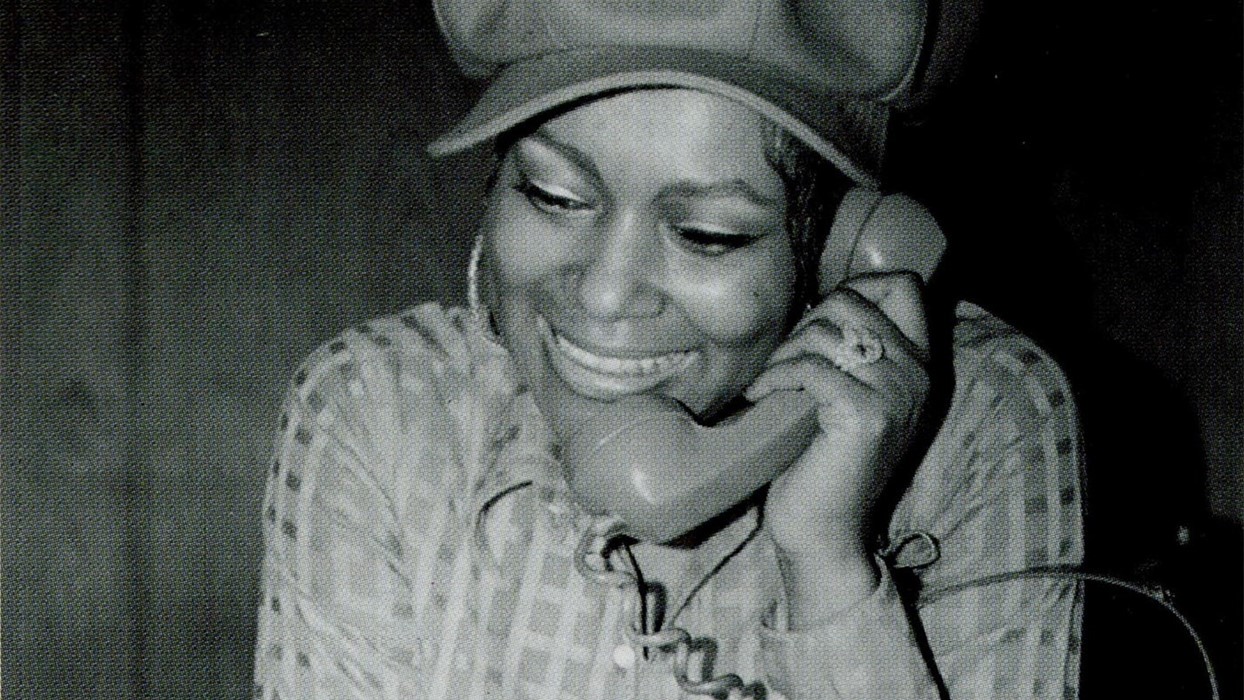

If Sylvia Robinson were still alive today (sadly she passed away in 2011 at the age of 76) she would have certainly been hankering after one of the Stephen Jones-designed hats from the Marc Jacobs show – a style of headwear that the record producer wore in abundance during the 1970s. Alongside towering newsboy hats, Robinson’s signature style consisted of a thick plait, with wisps of baby hair and goliath earrings framing an alluring visage, a look clearly demonstrated on the album cover of her 1973 single Pillow Talk. For a notable performance of the single on Soul Train in 1974, Robinson wore a head to toe metallic purple ensemble, featuring knee high platform boots and a beaded bralette: a clear a pre-cursor for the kind of looks that we would see in the 1990s on the likes of Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown. During an interview with Dazed in 2000, Robinson declared: “I wore clothes designed by Felix DeMasi who was known for doing clothes on the big gay entertainers, very creative you know”. Very creative indeed.

Seminal Moments

“Sylvia?” “Yes, Mickey?” “How do you call your lover boy?” “Come here lover boy!” if those spoken word lyrics sound familiar, then you are right in thinking that they hail from the Bo Diddley penned 1956 hit Love is Strange by Mickey & Sylvia. And yes, you are also right in thinking that they are sung by no other than the heroine of this article, Sylvia Robinson. After her stint as part of a musical duo, in 1968 Sylvia became one of the few female record producers of the time, helping to create such hits as Love On a Two-Way Street for The Moments and Shame, Shame, Shame for Shirley and Company. During the late 1970s, her son Joey Robinson Jr. brought a group of school friends home to rap for her and Sylvia immediately whisked the three boys – Big Bank Hank, Wonder Mike and Master Gee – into her studio, naming them the Sugarhill Gang. As we now know, Rapper’s Delight is one of the most revered hip-hop tracks of all time, selling 50,000 copies per day. Subsequently, the label Sugar Hill Records was born, with Sylvia at the helm as CEO, championing the likes of Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five, and The Sequence (of whom Angie Brown was the lead singer) paving the way for a new musical genre.

She’s an AnOther Woman Because…

It wouldn’t be overly dramatic to say that one of the ongoing travesties of the 20th century is the fact that Sylvia Robinson does not receive the wide recognition she is due as one of the defining figures of a cultural movement. As her son Leland Robinson Snr hypothesised: “I think that if it was a man in her position that started rap music then he would have been glory to God, but being that it was a woman, I just think that they don’t recognize it as being the person that started a legacy.” So, for carving out a piece of history during an era where the odds were stacked against her not only because of her gender (with the musician exclaiming that she “just wanted to say things that women wanted to say, but were afraid to”), but also the colour of her skin, Robinson receives the title of AnOther Woman, as a gesture of our admiration. For truly, she is an example of of dancing to the beat of your own drum – whether that beat hails from a sample machine, turntable or otherwise.