We decipher the lethal beauty of Charlotte Rampling in The Night Porter, the provocative and polarising film which was a key influence for Gareth Pugh’s A/W17 collection

“If you don’t love pain, you won’t find The Night Porter erotic – and by now, even painbuffs may be satiated with Nazi decadence,” so read The New York Times’ review of Liliana Cavani’s provocative, controversial 1974 film. And whatever your stance on The Night Porter, there is plenty of pain. Set in Vienna in 1957, it stars Dirk Bogarde as Max, a former SS officer now attempting to bury his past, working as a porter at a high-end hotel. It’s here that, by chance, he’s reunited with Lucia (Charlotte Rampling), the woman he abused and embarked on an ambiguous sadomasochistic affair with during her adolescence in a concentration camp. When she checks into the hotel with her new husband, it’s only a matter of time before the affair resumes.

Unsurprisingly, with its difficult-with-a-capital-D themes and taboo subject matter, The Night Porter polarises opinion. On the one hand, it’s pulp that gets its kick from exploitation – a bad taste eroticising of human suffering; on the other, a poignant love story about two lost souls who would rather destroy themselves than be without one another, a sort of Romeo & Juliet with Nazis. Whatever side you watch from, the big plot twist on viewing the film now, however, is quite how shocking it still is. Time has done nothing to diminish that; in fact, it’s difficult to imagine it even being made today. Thank goodness it was however, as the boundary-pushing exploration of a psychosexual nightmare still raises pertinent questions. We take a look at some of the key lessons this morbidly fascinating and undeniably stylish film can teach us.

1. A good look doesn’t always come from a good place

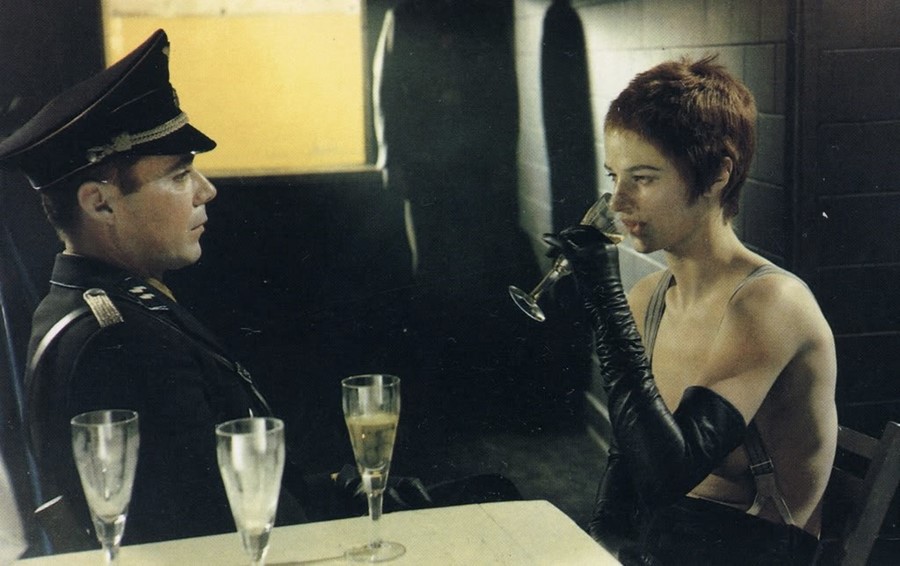

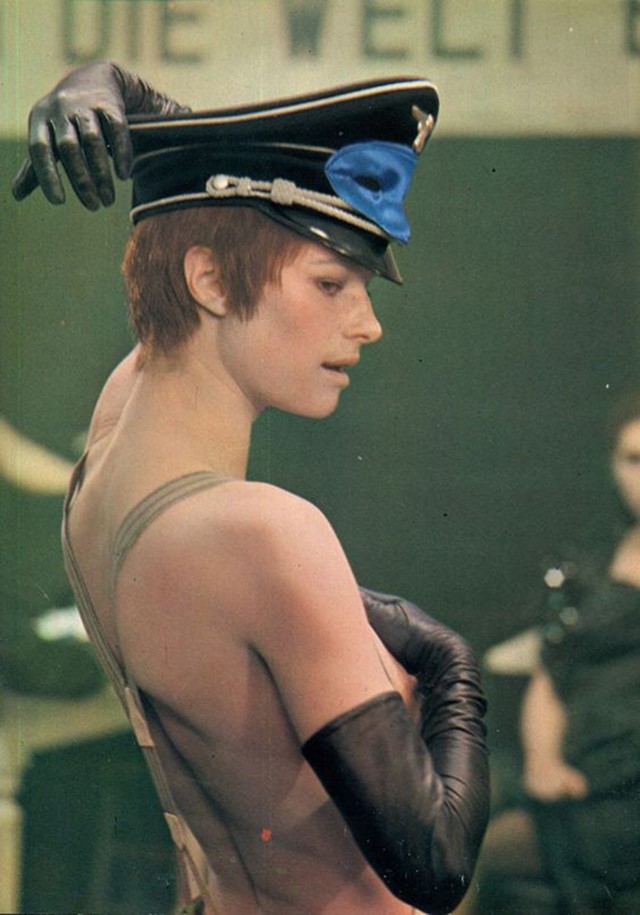

The image of a half-naked Rampling in braces, elbow-length gloves and a peaked SS cap singing Marlene Dietrich’s Wenn Ich Mir Was Wünschen Dürfte to captivated Nazi guards, is the film’s most memorable moment and one that has sashayed out into wider pop culture; this iconic image has been riffed on by everyone from Siouxsie Sioux to Marc Jacobs (see Louis Vuitton A/W11) and Marilyn Manson. Most recently, Gareth Pugh drew on the scene with his A/W17 collection, his women a symbol of “lethal female resistance”. When what the SS stood for is so obviously abhorrent, wherein lies the appeal of the look? Susan Sontag tackled this head on in her 1975 essay Fascinating Fascism, which questioned why Nazi Germany has become erotic and the SS a symbol of sexual adventurism. “The SS was designed as an elite military community that would be not only supremely violent but also supremely beautiful,” she writes. Her assertion that “most people who are turned on by SS uniforms are not signifying approval of what the Nazis did” might make anyone captivated by that precise, powerful image of Rampling feel a little better about it.

2. You are what you wear

In the world of The Night Porter, costumes are laden with symbolism, and uniforms are one of the film’s leitmotifs. Rampling’s character arc can be traced through her clothes: there’s the pink dress she wears as a carefree pre-imprisonment adolescent (later raped by Max, putting her in a version of it so he has his “little girl” back), the sexualised SS cabaret clobber and then the tightly belted camel coat, skirt suit and pearls, which semaphore the veneer of adulthood, respectability and restraint. When Max takes off those polite pearl earrings and tosses them to the ground, the no-holds-barred affair begins in earnest.

3. Underestimate a woman at your peril

The temptation is to read Lucia as a Stockholm Syndrome-afflicted victim. And of course, in many ways she is, but in Rampling’s steely portrayal she’s also a powerful figure, one who can harness her sexuality to powerful affect, with her husband referring to her as a “strange creature” – she is no one-note victim. Flipping the sadomasochism script of their relationship, for instance, at one point she forces Max to walk on broken glass. That strange cabaret moment, meanwhile, enthrals her captors and suggests that Lucia drew on her potent sexuality to survive. The scene ends with a biblical allusion to another powerful woman – Salome – as Max presents Lucia with a gift to signify his gratitude: the head of a man who had tormented her. Another critical lesson there: open a present from a Nazi with caution.

4. Guilt complex? Work a night job

“I have a reason to work in the night… I have a sense of shame in the light,” explains Max of his post-war career choice that involves simply “[being] nice to people”. That he might skulk in the shadows but ultimately has to face his demons in high definition has karmic significance: you can run, but your past will always find you.

5. Sex and power are inextricable

The Night Porter is almost baroque in its excess. This – coupled with wild historical inaccuracies, implausible plot twists and cartoonish Nazis – allows us to view the highly stylised, operatic melodrama through the lens of symbolism. So, the sadomasochistic relationship which makes the 50 Shades franchise looks like Disney becomes less about a specific relationship and more about archetypes (i.e. the master and the slave). Thought of like this, we can see the film exaggerate an ode to the concept that ‘power is sex, and sex is power’, one that remains as relevant as ever as a solid concept in a murky, ambiguous film.