Where most feminine fragrances sit on a sliding scale between clean and cliché, two industry greats, Frédéric Malle and Alber Elbaz, have joined forces to create a scent that evades such elementary definition

In an industry where celebrity perfumes are sold by the caseload, and fashion houses use branded scents to bolster their bottom lines, Frédéric Malle’s approach to creating fragrance is certainly appealing. In fact, the brand explicitly states that, “out of respect for both clients and perfumers, Frédéric Malle is not interested in ephemeral creations,” that it refuses to subscribe to trends in the market, that it is exclusively interested in creating perfect scents that stand on their own merit. After all, Malle – who describes himself as the “editor” of the brand, enlisting some of the industry’s most renowned artistans to create some of their best work – grew up in the industry, the grandson of revered perfumer Serge Heftler-Louich, and learned to evaluate fragrance on merit above all else. So, while such a venture might be commonplace within the market, collaboration with a fashion designer is not necessarily something to be expected of him.

The first time that Malle embarked on such an endeavour was in 2013, when he worked with Dries Van Noten to compose a scent with Bruno Jovanovic – and it received almost universal acclaim. It has taken him four years to team up with another designer – this time, Alber Elbaz – because, “every time I saw somebody I was always asked ‘who is next?’ and I was frightened that designers or artists would overshadow the perfumers.” But Elbaz felt different to him – because, alongside growing up with perfume, Malle also grew up with his mother’s love for Yves Saint Laurent, who appointed Elbaz his successor at his house. “He was very modest there; very reverent for Saint Laurent – what he created was very much Saint Laurent, but his own interpretation of it,” he explains. It is this modesty that particularly reverberates with Malle’s own approach, one that explicitly celebrates those usually kept behind the scenes.

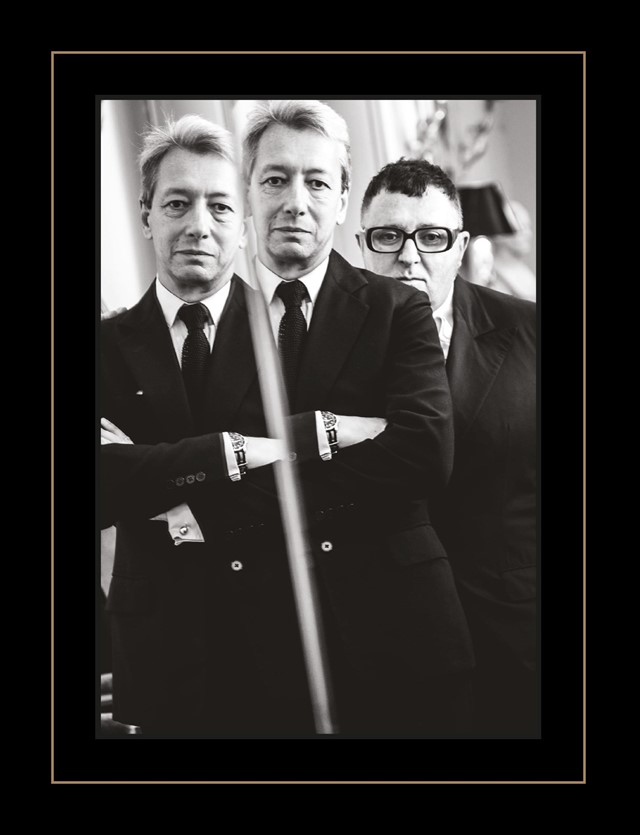

So, Malle reached out to Elbaz through a mutual friend (the jeweller, and Lanvin’s former accessories designer, Élie Top) and, over a series of lunches, they decided to work together, using a fragrance that Malle had been creating with Dominique Ropion as the foundation for their project (Ropion is one of Malle’s most prolific perfumers, having created scents like Carnal Flower and Portrait of a Lady with the house). What evolved was Superstitious, a grand aldehyde floral: the sort of scent in which you can’t recognise any particular notes (save glimpses of jasmine, rose, vetiver and amber) but simply an immersive carnality. It is round and warm, with fleeting moments of sandalwood and vetiver, and distinctly yet amorphously floral while avoiding any of the garish clichés of feminine fragrance. In a market where a sweet white floral, or a heavy, musky oud, are positioned as the binary options for a woman seeking a scent, such quiet complexity is distinctly compelling.

Not only is such a creation one of the most impressive thus far in Malle’s olfactive library, but it speaks to the heart of what makes his brand – and Elbaz’s own work – so particularly enchanting. “During our first lunch, we agreed that life is too much about systems and recipes,” he explains. “Alber said that he thought people should be a little more superstitious, believe more in karma and talent and luck than recipes.” So, aptly titled Superstitious, and with an accompanying, free-hand logo originally scrawled by Elbaz during that first meeting, their project took form, the scent evolving (suitably romantically) over a series of Parisian lunches.

“The way that I see Alber is that he creates these very free-flowing dresses, which are like a second skin, but when you look inside them there is a real architecture to them,” says Malle. He’s right, of course: it takes a true mastery of construction and technique to create the illusion of effortlessness that Elbaz has achieved throughout his career, in the same way that it takes a deep understanding of scent to create a fragrance not tied to any particular ingredient, stereotype of womanhood, or marketing formula. Here, rather than one note, or image, leading the way, “you don’t really know what you are smelling,” he says. “You are just smelling a scent. Like you would just see a dress. It’s a good one, I think. I suppose I’m not really the one to say…”