As the German director’s revered film returns to UK screens for the BFI’s Fassbinder retrospective, we examine the revealing costumes of its leading lady

In 1978, just four years before his drug-induced death at the age of 37, Rainer Werner Fassbinder made The Marriage of Maria Braun, the film that would finally grant the prolific German auteur the commercial success he had long striven for. The story of its first screening has gone down in cinematic history. Fassbinder began shooting in January and finished in March the same year. In May, his previous film Despair, an English language adaptation of the Nabokov novel upon which the director had steeled his hopes, met with a disappointing reception at Cannes Film Festival. Undeterred, however, Fassbinder ordered the answer print of The Marriage of Maria Braun to be flown in, setting up an impromptu late-night screening that saw all the film industry bigwigs squeezed into a tiny theatre, interests piqued. As the majestically shot, brilliantly scripted critique of Germany’s post-war “economic miracle” drew to its climactic conclusion, the applause was resounding, Fassbinder and his cast the surprise heroes of the festival.

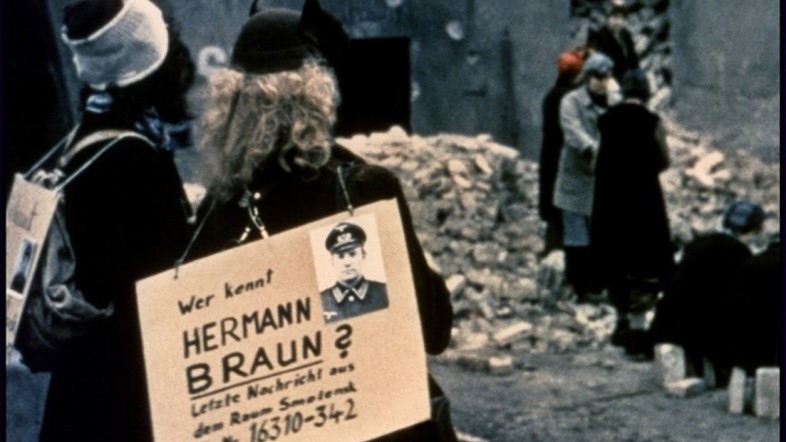

Of all the film’s stars, none shines brighter that Hanna Schygulla as the cool, impenetrable Maria, whose unwavering ambition in love and business proves both her enduring strength and ultimate downfall. Fassbinder had originally cast Romy Schneider in the role but later dropped her in favour of Schygulla, a former school friend and star of many of his earlier works. Maria is a pretty young woman who marries a soldier named Hermann Braun during World War Two, spending just “half a day and one night” with him before he returns to battle. Shortly afterwards he is announced missing – presumed dead – and Maria takes up with an American GI named Bill. But all is not as it seems – Hermann returns, sparking a chain of events that result in Maria’s accidental slaughtering of Bill and her husband’s subsequent imprisonment after opting to foot the blame. For the duration of the film, we watch as Maria, a self-professed “master of disguise” undergoes a gradual but profound evolution, supported by an exquisitely varied wardrobe by Barbara Baum, in a bid to salvage first her own and then the couple’s future. Here, as the film returns to UK screens as part of the BFI’s dedicated Fassbinder season, we decode the symbolic messages her myriad costumes hold.

The Signature Look

We first meet Maria on her wedding day. She is wearing an A-line dress in fine white lace and a veiled headpiece, while bombs fall and debris rains down like confetti. Cut to Maria’s mother’s house, where our protagonist is dressed simply but immaculately in a blue dress, brown sheepskin coat and matching, angular hat. She announces that although there’s no longer much of a market for wedding dresses, she has swapped hers for a shaving set – the first indication of her shrewd business mind. The news of Hermann’s supposed death prompts another transaction and the first of Maria’s various transformations: she swaps a brooch for a dress – “black, short sleeves, decollage” – in order to secure a job at an off-limits bar. Her mother shortens the hem, while her friend Betti styles her hair in a “poodle”-like updo supposedly fashionable among Americans. Add to the equation rouged lips, a smattering of diamantes and a sultry pose, and the role is hers. Maria, we are swift to learn, knows how to get what she wants – especially where men are concerned.

The same beguiling black dress proves the catalyst for her next job offer too, when Hermann’s jail sentence forces her to take control of the duo’s finances. She sneaks into the first class carriage of a train, slips into the gown and charms a textile mogul named Karl Osmond, who offers her a job before the journey’s up. From the first shot of the blonde beauty in her new role, another change is apparent: she radiates grace, charm and self-confidence in an expensive looking, voluminous black skirt and pale blue top, the tie of which accentuates her small waist. Osmond falls heavily under her spell and the pair embark on an affair orchestrated by Maria, who frequently reminds the besotted businessman of this fact, as well as asserting that it is “not me [but] my work” that should dictate her position within the company. Thanks to both, one can only assume, she soon rises through the ranks, her wardrobe growing ever more lavish – coats trimmed with leopard fur, organza dresses, intricately embellished hats, chic black polo necks and shimmering pearls abound.

By the time she and her estranged husband are reunited, after no shortage of drama, Maria – now an impressive but icy powerhouse, decked in a sharply tailored, pale grey skirt suit – has just purchased her first house. But the return of her husband, for whom she has reserved her heart (if not her body) all these years while barely knowing him, reveals her vulnerable side once more. In the film’s final scenes, she flits manically from outfit to outfit – first a smouldering, black satin corset and suspenders that hold up grey silk stockings, then a crumpled navy dress, and finally an all white suit (perhaps an attempt to evoke their wedding day) – an unsettling precursor to the explosive, enigmatic ending.

The Modern Manifestation

While a number of Maria’s outfits are distinctly 1950s in tone, her carefully cultivated style nevertheless offers up a number of opportunities for modern interpretation. Her cherry red lips and matching nail varnish, for example, prove a timelessly chic combination; a look you can recreate using a Chanel lip gloss and complementary polish. Similarly, when it comes to strong, sexy lingerie, Maria’s take is hard to beat. Agent Provocateur’s Damson or Lyst corset in black offers a covetable contemporary alternative. Complete the effect with suspenders, stockings and loose, tousled curls. There are also lessons to be gleaned from Maria’s empowered approach to her appearance – namely her winning resolution to dress for success. But our heroine serves as an important reminder that material wealth can come at a price. As French film critic Jean de Baroncelli – who viewed Maria as an allegory of postwar Germany, complete with skewed moral compass – famously proclaimed, “[she’s] a character that wears flashy and expensive clothes, but has lost her soul”.

The Fassbinder retrospective is at BFI Southbank, and on BFI Player, from March 27 until May 31, 2017.