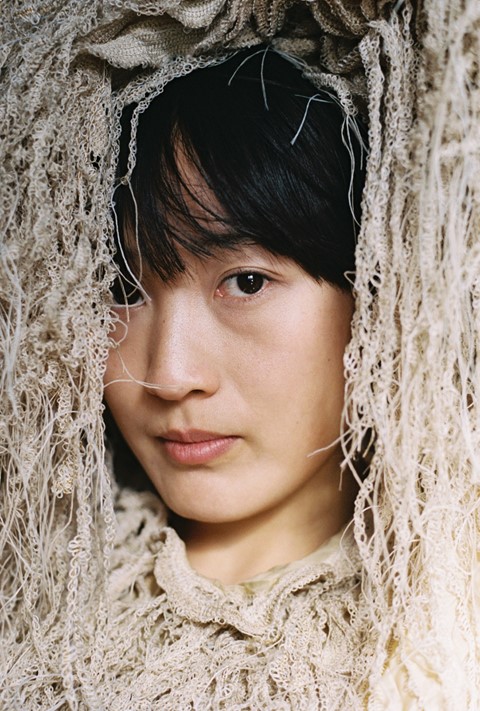

We meet the founder of Asai, whose contemporary look at his urban adolescence manifested in remarkable craftmanship for his debut London Fashion Week collection

When I arrive at A Sai Ta’s home in Seven Sisters, it has been over a month since he staged his London Fashion Week debut (as Asai) under the Fashion East banner, but assorted samples are still strewn about his spare bedroom. Tie-dyed tights and bleached silk skirts spill out of plastic bags; perfectly formed little 90s jackets and dresses made from chains of shredded overlocking all mixed up together. There is hardly a full look or a garment bag in sight – and that sort of confident eclecticism is perhaps what was just so appealing about Ta’s first show. Its vibrant diversity and artful dishevelment looked a little like late-90s Gaultier reworked for the modern day – and he consciously redrew the tropes of that era, imbuing them with a contemporary relevance rather than unnecessary nostalgia. I turn up at the house around lunchtime, and Ta has spent the morning officially registering his company. It feels like the start of something quite exciting.

Ta grew up in London, and he is perhaps the prime embodiment of this city, not just in the sense that he plays to his mixed heritage (although that, too – his mother is Vietnamese, his father Chinese, and his show notes took the form of a reappropriated noodle bar menu), but that his aesthetic incorporates the teenage style tribes that can be seen lurking in parks or congregating on housing estates. He grew up in Woolwich, the youngest of seven children, although he moved all around the country once his parents had divorced and thus attended endless different schools for which he never had appropriate school uniform. His mother was a seamstress, making clothes for high street stores like New Look, and she would bring bags of sewing home from the factories that her son would then spend his evenings unpicking; by the age of eight, he was drawing designs for his own pieces and sending them off as submissions to Freemans and Littlewoods catalogues.

“The girls at school who would have Jane Norman bags and gypsy belts… there was this kind of brashness to them. Those girls felt like they were invincible” – A Sai Ta

But, by the time he got into secondary school, he was hanging around with local gangs, staffie and BMX in tow, hair spiked into “that really brash, loud, urban style,” listening to garage and working in a local Chinese takeaway (the same one, Blue Sea near Greenwich, which inspired his show notes) – and it is this period which directly informed this collection. “I feel like the work I’ve done recently has been mostly me as a teenager,” he explains, “or at least, the type of girl who I would meet at that age. The girls at school who would have Jane Norman bags and gypsy belts… there was this kind of brashness to them. Those girls felt like they were invincible; had this sense of self-entitlement, but not in the privileged way – in that, ‘I’m from a council estate and I can do whatever I want because I’m the boss of me’ kind of way.”

While such a style more instinctively conjures ideas of sportswear, of tracksuits and hoodies, what Ta creates is far more nuanced than that – it is only when you look a little closer at the pieces that those millennial codes become particularly visible. There are those gypsy belts formed from leather disks which were once particularly covetable; tight, off-the-shoulder tops he describes as “quite chavvy”; seamless boob-tube dresses and skirts formed from what he has termed “interlocking embroidery” – a technique he has created using chains of overlocked stitching “that keep growing and growing off the machine,” building pieces “almost like pottery”.

“Not everything is about expensive clothes, or that Céline handbag – sometimes it’s about the people on the bus excited about Michael Kors” – A Sai Ta

That is the other thing which is compelling about Ta’s work: it is executed with remarkable finesse. While he’s spent plenty of time designing menus at the noodle bar, or manning the tills at H&M – experiences which have visibly marked one part of his design process – he has also worked underneath Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski at The Row, and at Kanye West’s Yeezy. “At those places, I got to learn precision – particularly of the pattern-makers and the knitwear designers,” he explains. “They really took their time and everything was just right – but I also learnt that kind of wasn’t my style. I suppose that I always wanted to find my own way of doing things… at Central Saint Martins, I saw people come back from internships at places like Dior and Lanvin and their collections would just look like that.” Nonetheless, the technical prowess he observed at such places seems to have stuck; even his more experimental techniques are executed with skill that gives little indication this is his first proper collection.

“Both the ideas and the garments in this collection are meant to be taken home with you – a takeaway,” read the collection notes/menu. “A lot of work goes into a takeaway, but it also arrives home in a state of disarray. Something changes when taken out of context.” “I guess, essentially, it’s about playing with familiar things – but recontexualising them,” Ta explains now. In an industry which can quickly dismiss, or parody, certain facets of womenswear, and the women who might wear such clothing, such an authentic embrace – offered without even a hint of irony – feels thoroughly refreshing. “Not everything is about expensive clothes, or that Céline handbag,” Ta summates. “Sometimes it’s about the people on the bus excited about Michael Kors, or their new thing from the market. That excitement is valuable, too.” And that fresh excitement, presented as beautifully as it is by his hand, feels almost tangible.