Inventing subtly subversive power dressing for the ravers of the 80s, Lang's S/S92 collection brought the anti-fashion crowd into his fold

Raised in Tyrol, Austria, by his grandparents, it wasn’t until 1986 that Helmut Lang joined the Paris fashion week circuit with his now iconic and deconstructionist designs. It was in the early 90s, according to fashion critic Sarah Mower, that Lang began to bring an anti-fashion crowd into the catwalk fold, offering the punks and ravers of the 80s “rites of passage into adulthood” via subtly subversive power dressing that lent “an air of polish to otherwise underground references”. Lang brought an element of dishevelment to the established European scene, as Anna Wintour explained back in 2000: “Helmut came along and at first it was, ‘Wait a moment, what’s this? This is not in the spirit of the mid-80s,’ which was all about opulence. But then everything crashed and fashion reflected that and Helmut was there to take advantage.”

“Of course, we used to be seen as minimal, but that was at the beginning,” Lang told Susannah Frankel back in 2010. “When we started out in Paris it was all about Mugler, Montana, Gaultier, that’s where we came in; by comparison our clothes just looked completely different.” In transplanting his brand to New York in 1998, and staging his show before the season had even begun, Lang threw the whole fashion month schedule into disarray and is responsible for the New York-London-Milan-Paris order as it stands today. It’s the momentous mark he made in the early 90s that enabled him such a coup. Flicking through the Helmut Lang archives, his S/S92 collection appears more relevant than ever; threads and silhouettes spool from that dark Parisian runway into the recent A/W17 collections. Margiela and Jil Sander flanked Lang during this peak 90s minimalist moment and the latter’s play on synthetic fabrics (laminated leathers and plastic-coated satins) and sexuality (girls in large leather hipster briefs with matronly aprons for tails, their thighs and arms smeared with paint) prefaced the kind of lo-fi irreverence that has dominated the influential catwalks of Balenciaga and Vetements of late.

The Show

“There is a grim aspect to his clothes, felt not only in his preference for black leather and wet-looking synthetics but in his hardcore disaffection for established fashion. Unbound by conventional good taste, he is free to experiment,” wrote Cathy Horyn for the Washington Post in 1992. “The upshot is a point of view that is entirely original, and in that sense, more genuine.” In a catwalk collection where rubber bands were worn as garters, ultra sheer tights came in black and red and loose T-shirts deferred to the bare breasts beneath them, this almost-but-never-quite theatrical play was softened, integrated into something altogether genuine and worn-in. The list of subtle textural tweaks is long: the cut of a bra and pant look is cumbersome while a sheer black body is ever-so-slightly slouchy; a satin mini dress grounded with flats while threadbare linen jersey lends authenticity to a plastic skirt; a look with a black bra beneath a white T-shirt breaks the showy statement of an army of nipple-grazing looks.

The notion of Lang’s work as anti-fashion rings particularly true in this collection – there’s a rawness and offness that came to define the compellingly bitter irony of the 90s. Changing the landscape of good taste, Lang worked plastic-coated mesh, tightly woven feathers and panels of plastic beading alongside precision-cut crombies, boxy tailoring and suiting that began to fill the offices of the creative industries.

The People

Helmut Lang was one of the first designers to flout the ageist traditions of the European runways. Though young waifs were all present and correct – Stella Tennant, Kirsten Owen, Kate Moss, Kristen McMenamy all became favourites of the brand (many of which he’d only allow to exit once per show to avoid being too crass, or needy of celebrity association) – Lang would send his friends of all ages down the runway too, somewhat reminiscent of the moves of Eckhaus Latta, Marques’Almeida or Demna Gvasalia at Balenciaga. For Dries Van Noten’s 100th show for A/W17, the designer reunited 54 of the models who’d walked for him since 1993 in an inclusive celebration reminiscent of Lang – not least due to the direct overlap in girls. “What mattered to Lang was not who was young, who’d been around, or how old they were. What came across was his admiration of character, his loyalty to his own clan of the cool,” wrote Sarah Mower last year.

As photographer Elfie Semotan – who first walked for her friend Lang at the age of 51 – remembered, “The way Helmut simplified hair and make-up didn’t make him look simple, but really avant-garde, always the freshest and the most modern in the best sense. The models knew that, they loved it, and knew they were chosen not only for their looks, but also for their personalities.” Always moving unpredictably, Lang’s refreshing attitude to models was no easily defined anti-model statement: blonde bombshell Cordula Reyer had at least two outings at this particular show, as did the angelic, doll-like Cecilia Chancellor (who re-emerged at Dries this season too). Later, Lang would use first-wave Supers from Naomi Campbell to Christy Turlington and Linda Evangelista long after the second-wave had turned the tide. Though he’d eschew classic conventions, the designer would ensure that you’d never be able to guess exactly how.

The Impact

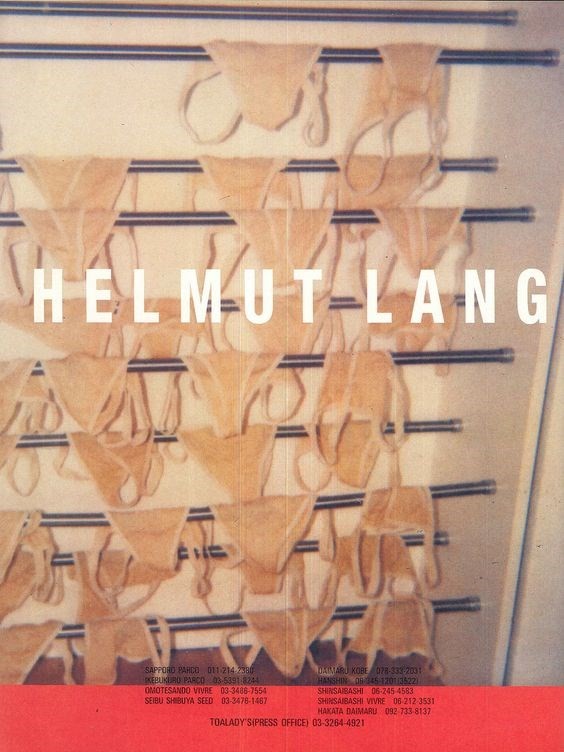

At his first Autumn/Winter 2017 show for Calvin Klein, Raf Simons took the powerhouse brand back to its American minimalist roots, in a move akin to that Paris-to-New York transition that Simons’ known idol Lang had also taken. Plastic-coated checked coats, square-ish tailoring and vacuum-packed feathers threw audiences way back to the synthetic cool of Helmut Lang with a pleasing dash of symmetry. Lang’s impact is still, for all accounts, endless. The campaign image for S/S92 – a flash film snap of nude thongs draped over gymnasium-style bars, its photographer unknown – was the beginning of Lang’s deliberately evasive approach to advertising.

A unique statement at the time, Lang refused the hard sell and continued to do so, running Robert Mapplethorpe photographs (including a self portrait of the photographer) entirely absent of product. When Lang released his first fragrances in 2000, Helmut Lang Parfum and Helmut Lang Eau de Cologne, the ad campaign concocted with artist Jenny Holzer consisted only of block, lyrical text. The product-free campaign has since become code for an authoritarian brand of cool, adopted by the likes of Marc Jacobs, Hedi Slimane at Saint Laurent and Loewe. What Lang had brought to the market was zeitgeist, a mood, an idea; and his art-meets-fashion approach prefaced an intertextual relationship that seems utterly commonplace today.