The French film directed by Luis Buñuel championed women's erotic liberation, and reignited a new generation’s fading interest in couture

The sartorial impact of Luis Buñuel’s 1967 French surrealist satire Belle de Jour, based on Joseph Kessel’s 1928 namesake novel, continues to endure. In one of the most scandalous films of the decade, a sexually frustrated and bored bourgeois housewife, Séverine Serizy, played by an unwavering Catherine Deneuve, sought to satisfy her increasingly masochistic and elaborate erotic fantasies to escape from the gilded cage of her affluent Parisian lifestyle – complete with grand piano and French maid – by spending her afternoons working as a high-class prostitute whilst her husband is at the office.

Alongside Hélène Nourry’s costumes, Yves Saint Laurent designed the multifaceted female protagonist’s wardrobe. Previously, Saint Laurent had produced costumes for Claudia Cardinale in The Pink Panther (1963) and for Sophia Loren in Arabesque (1966), but it was with Deneuve in Belle de Jour that he truly left his mark on cinema. Saint Laurent’s contribution has been credited as having helped to make couture relevant for a younger generation in the face of the rise of ready-to-wear, and after Brigitte Bardot scathingly stated “haute couture is for grannies.” Deneuve and Saint Laurent first met in 1965, she became his muse soon after, and the pair went on to collaborate again and again, remaining friends until the designer’s death in 2008; the actress gaining her status as a style icon in the process. Here, we examine the lessons to learn from one of the most iconic films of the 20th century.

1. Dress for the occasion

Whether après-ski or deviating into prostitution, act like a Parisian and always dress appropriately, no matter what the event. Yves Saint Laurent wanted to do for women in the 1950s and 60s what Chanel had done in the 1920s: to design for a muse who was an increasingly active member of society and in charge of her own decisions. In Belle de Jour the designer created a wardrobe to enable exactly that. Somewhat ironically, Séverine often wears Roger Vivier’s pilgrim pumps (also a favourite of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis), a feminine yet practical style of shoe suitable for a variety of occasions, fantasy or reality.

2. Read the sartorial subtext

Through Saint Laurent’s clever uses of colour and texture, Séverine’s wardrobe can seamlessly shift from domesticated housewife to high-end call girl. Whilst she is subservient, her clothes are of soft and fluffy fabrics in neutral colours, but when independently pursuing her desires she wears bold primary shades. Entering Madame Anaïs’s brothel, for example, she wears a militaristic wool coat and dark sunglasses, and on another occasion a shiny black rubber mac (which was enviably evoked throughout Anthony Vaccarello’s first two collections for Saint Laurent). In the majority of her fantasies, on the other hand, Séverine embodies the scarlet woman, dressed in red. In one, she wears a floating pure white silk dress, but it is quickly soiled by dark brown mud hurled at her alongside reams of insults by her husband’s friend Husson.

3. Stay carefully coiffed

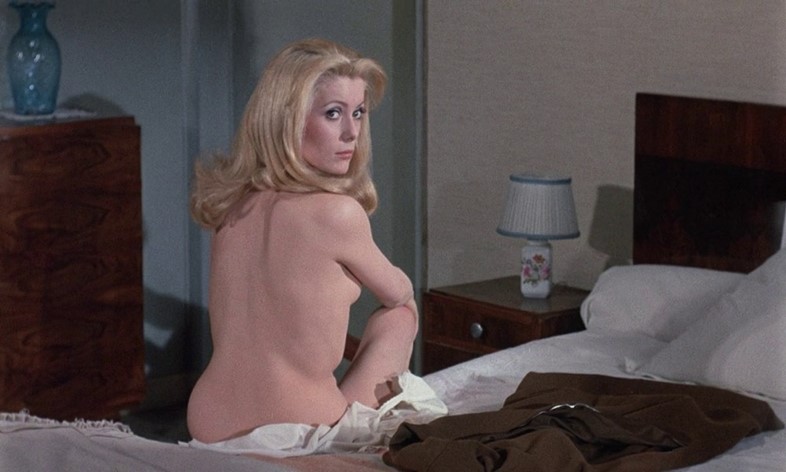

Deneuve’s peroxide blonde locks are almost as good an indicator of her character’s transgressions as her clothes. In the role of ‘wife’ a hair is never out of place, it is usually kept back with a headband, stored under a hat or tightly coiffed into a matronly chic style. In contrast, when spending her days inside the brothel her hair is released, cascading around her shoulders, breaking free from its tightly tamed and hair-sprayed updo as she simultaneously breaks out of the confines of banal bourgeois existence.

4. Exude Parisian nonchalance

Despite the film’s underlying assertion that money cannot satisfy every need, Séverine’s clothes demonstrate, in the perfect paradox, that effortless French style can in fact be bought from Yves Saint Laurent. Exactly half a century on from Belle du Jour’s release, the infamous black wool and contrasting white collared and cuffed “precocious school girl” dress still stands the test of time. In fact, there are few of her couture pieces that would feel out of place on the catwalks of today; manifestations of Séverine’s wardrobe have appeared throughout the collections of Tom Ford, Stefano Pilati, and even in Hedi Slimane’s designs for the house.

5. Repressing your female sexuality will leave you in turmoil

Not only is Belle de Jour the first explicit exploration of female erotic fantasies dealt with in narrative film, but it is symptomatic of wider societal unrest. The film is both indicative of the changing roles of women but also the boiling political and economic anxiety throughout France – the Paris riots of 1968 occurred just a month after the film’s release – and across the globe. Famously anti-church and anti-bourgeois, Buñuel’s ambiguous ending passes no moralistic judgment, leaving it open for interpretation. Séverine is an atypical femme fatale, proving that if female sexuality is pushed aside and neglected for too long, chaos will ensue.