Sayoko Yamaguchi and her mould-breaking modelling career were the inspiration behind Kenzo's Spring/Summer 2018 collection: here's what you need to know about her

Who? Born in 1949 in Yokohama, one of Japan’s most populated cities, Sayoko Yamaguchi graduated from Sugino Gakuen’s prestigious design school in Tokyo. But soon after completing her education in design, Yamaguchi embraced her preference for wearing clothes rather than creating them, and began auditioning for modelling jobs. The budding model’s big break coincided with that of Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto’s. It was in 1971 that Yamamoto, who was the inspiration behind the cartoon graphics of Louis Vuitton’s recent Cruise 2018 collection, became the first Japanese designer to show in Europe, debuting his collection in London.

In 1972, with her doll-like okappa bob and oft-praised “almond eyes”, Yamaguchi made her modelling debut in the Paris show, and so commenced a glittering career. Becoming the first Asian model to grace the Parisian runways, Yamaguchi’s Japanese beauty entranced the industry in the West. The supermodel became a muse for Yamamoto, as well as fellow Japanese designers Kenzo Takada and Issey Miyake, and helped to embody a new wave of European appreciation for the Japanese aesthetic. Her rising profile in the early 70s saw her model for the crème de Paris too, from Yves Saint Laurent, Chanel, and Jean Paul Gaultier.

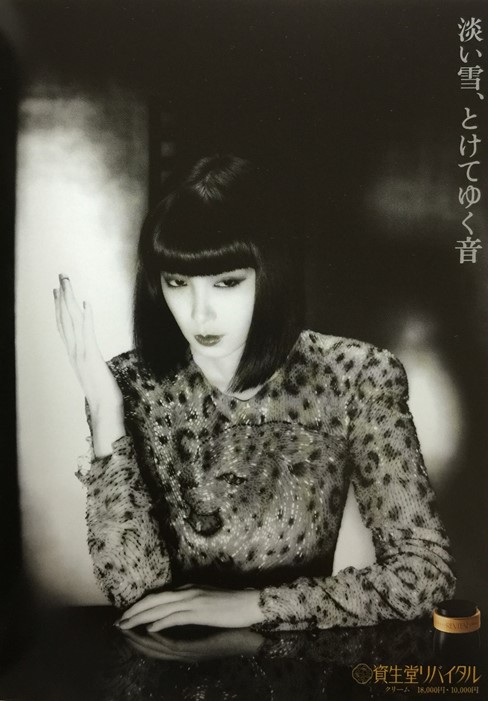

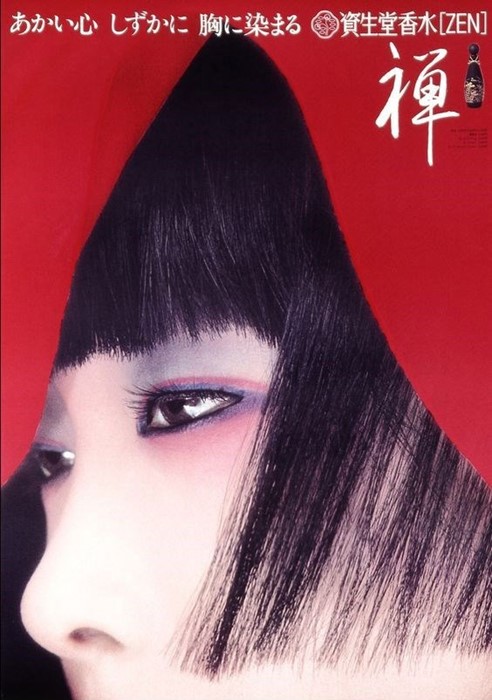

But it was not only Europe’s landscape that her image revolutionised so rapidly – Asia’s beauty standards were transformed too. In the 60s, almost 50% of models used in Japanese advertising were non-Asian, and Shiseido, the country’s largest beauty conglomerate, used only half-Japanese models right up until their signing of Yamaguchi in 1973. It was under this contract that, along with French artist Serge Lutens, the model created some of the most powerful beauty imagery of the decade, heralding a new appreciation of Japanese beauty.

What? When she died in 2007, every obituary hailed her raven hair and almond eyes, her “sidelong glances”, hey “mysterious gaze,” and not least her doll-like elegance. And while Yamaguchi’s popularity marked a diversification of beauty ideals, it simultaneously embodied a kind of Oriental fetishisation. “Despite her impressive eyes in the ads, she originally had round eyes. It was skillful eye make-up with eyeliner and her expressions that made her eyes look almond-shaped,” explained Sakae Tomikawa, Shiseido’s senior beauty director, who created Yamaguchi’s “mysterious” look in the brand’s ad campaigns. Such make-up mastery belies the marketable trait of Yamaguchi’s look – at once highlighting its power, but also the myth constructed around her.

In his book The Emerging Monoculture: Assimilation and the ‘Model Minority’, professor Eric Mark Kramer likened Yamaguchi’s Parisian debut to Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism, coined in his 1979 book of the same name. Kramer described the model’s look as “a Western version of what the exotic Orient should be,” explaining that, “the chic official version of beauty is generated by a tiny cadre of high fashion power brokers who then sell it to Oriental consumers as their ideal beauty”. While many journalists have maintained a cynical view of this double-edged sword of representation, Yamaguchi’s impact on the cultural landscape remains undoubtable. In 1977, Newsweek magazine named her one of the top six models in the world. It was a huge shift in the whitewashed media of the times, and ironic since Yamaguchi never referred to herself as such, preferring the term ‘wearist’ to ‘model’.

Sayoko Yamaguchi’s iconic style was recreated the world over in the form of “Sayoko mannequins”, displayed in the windows of stores like Harrods, London, and Barneys, New York, each imitating her dark bobbed hair and sidelong glances. Such mass-market appropriation of her look was counteracted by the revolutionary mannequin maker, Adel Rootstein. Rootstein’s rendering of Yamaguchi portrayed a bare-faced beauty, free from her heavy contouring make-up and, complete with a raven wig, served to normalise the supermodel’s fabled appearance, as part of Rootstein’s mission to diversify the department store. And though Yamaguchi’s image was endlessly reproduced, the wearist’s personal relationship with fashion was far more connective and tactile: she described the three key elements of modelling as kimochi (feeling), katachi (style) and ugoki (movement). Such a disconnect between the outside world’s perceptions of Yamaguchi, and her own, could be read as the cause of her later career change. She became heavily involved with the Japanese avant-garde art scene, collaborating with poet and dramatist Shuji Terayama and the Sankai Juku dance troupe, and starred in and designed costumes for film and stage productions. More recently Yamaguchi collaborated with next-generation luminaries like performer Fuyuki Yamakawa and Naohiro Ukawa, the founder of Tokyo club and online streaming studio Dommune, continuing her engagement with creatives until very late on in her life.

Why? Last week’s close to Paris Fashion Week Mens was seen in with Kenzo’s Spring 2018 Love Letter to Sayoko. Split in two halves, menswear and womenswear – the mens’ show was dedicated to contemporary Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto – Kenzo’s co-creative directors Carol Lim and Humberto Leon paid homage to the French brand’s Japanese roots. And, with an all-Asian model cast, stars Fernanda Ly, Manami Kinoshita and Mae Lapres emerged in homage to Kenzo Takada’s muse Yamaguchi, who had paved the way before them.

“Her originality lay in her capacity to offer chameleon-like qualities to endless inspirations,” sung the shownotes. “Upon looking through the many images in the house’s archives of her and Kenzo, we were inspired by her transformative character.” And so ensued an army of kaleidoscopic colours, clashing Bowie-esque stripes and acid-hued florals. Sporty 80s touches like ski pants and biker jackets rang through too, as well as silky sheens that recalled the high-shine glamour that defined Yamaguchi’s career. Year on year, diversity across the runways improves, although it’s by no means perfect – but how better to pay tribute to this icon than with a visual representation of the impact she made?