This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from October 31. Order here:

It’s a hot, sticky morning in Berlin and my phone buzzes with a WhatsApp call from an unknown number. The profile picture shows a Siamese kitten with giant turquoise eyes and a canary-yellow collar, while the number has a German country code. I answer hesitantly and hear Franz Rogowski’s voice. “I’m outside,” he says, his gentle lisp and strong German accent unmistakable.

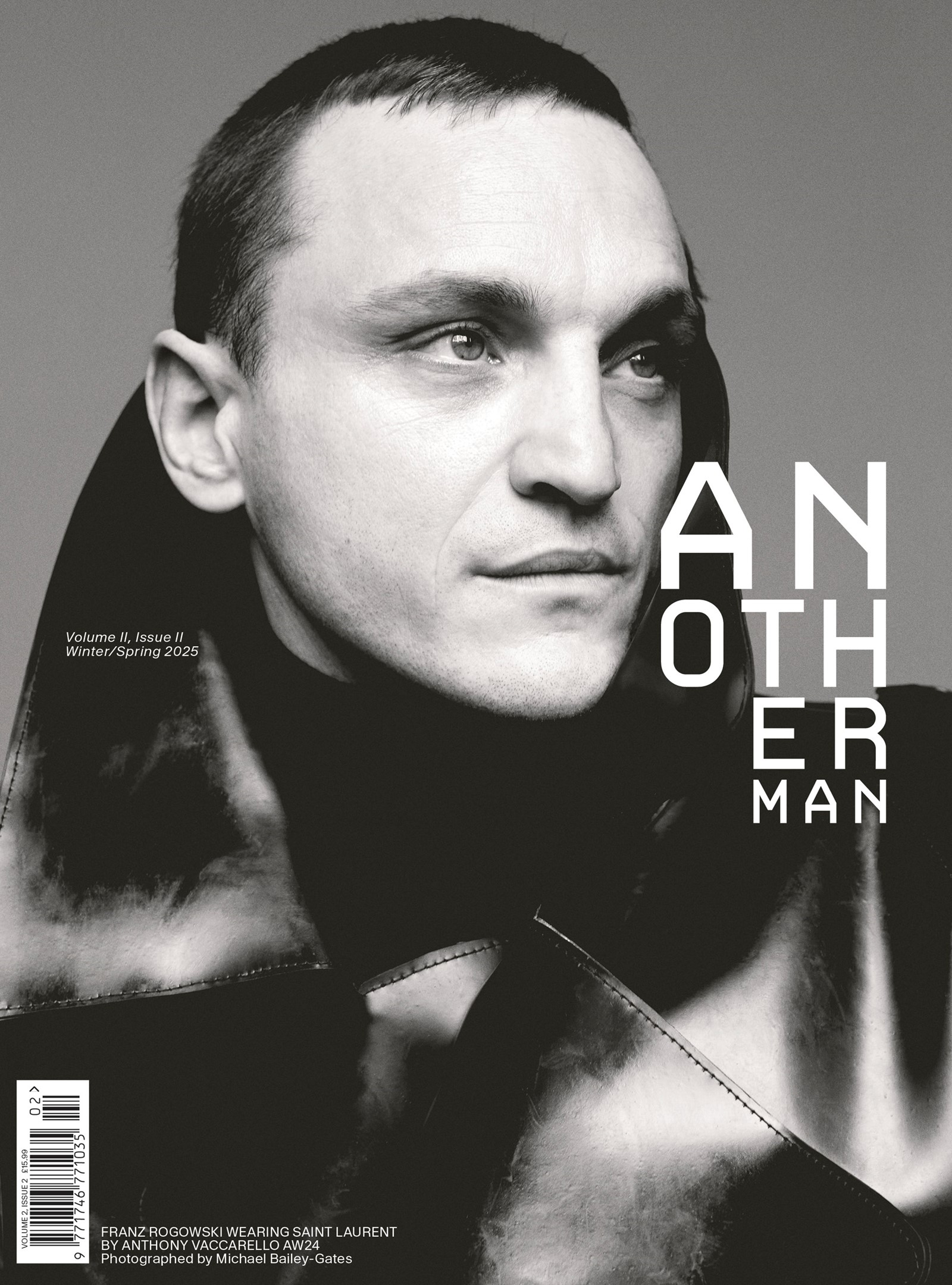

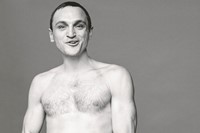

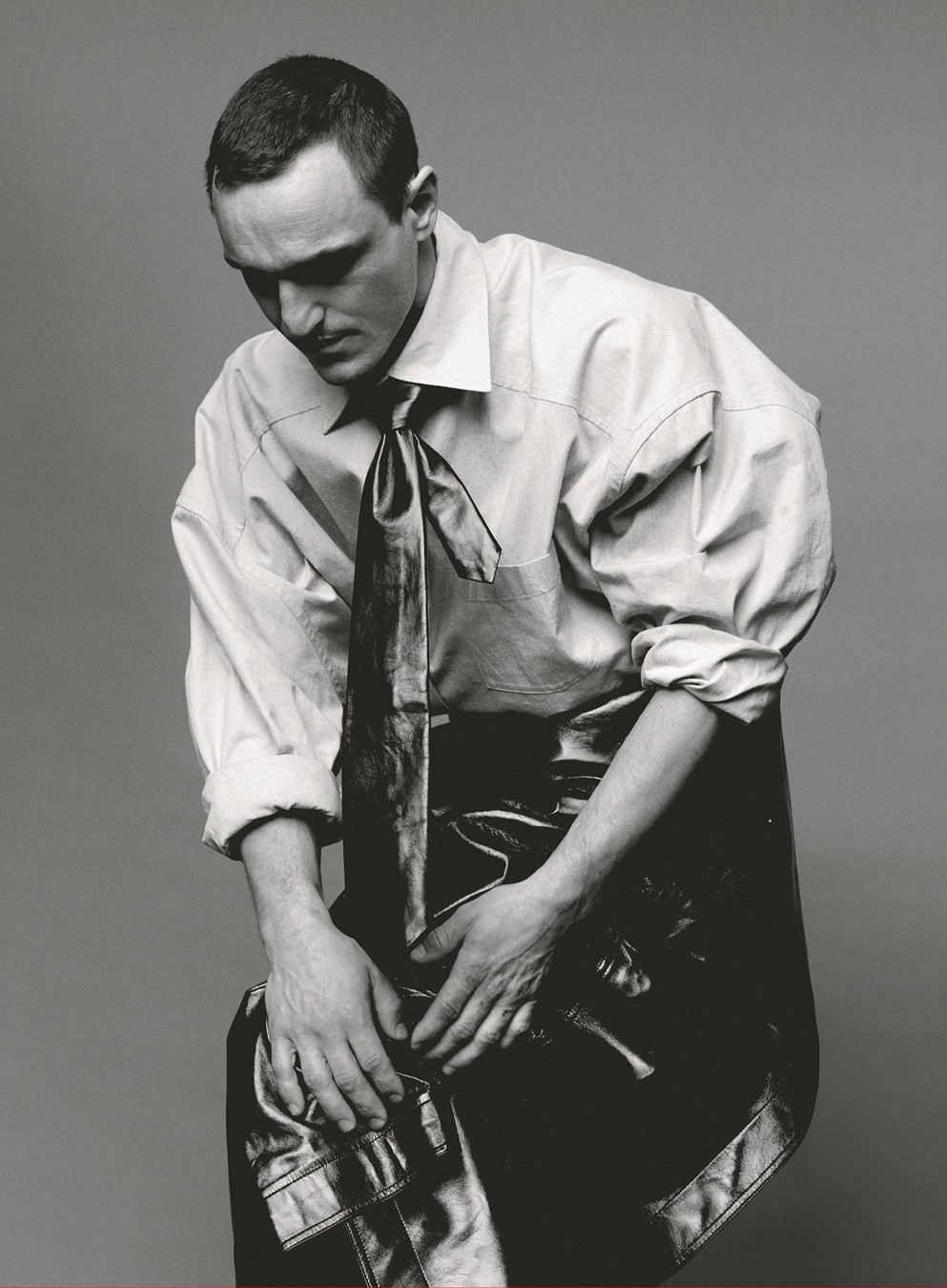

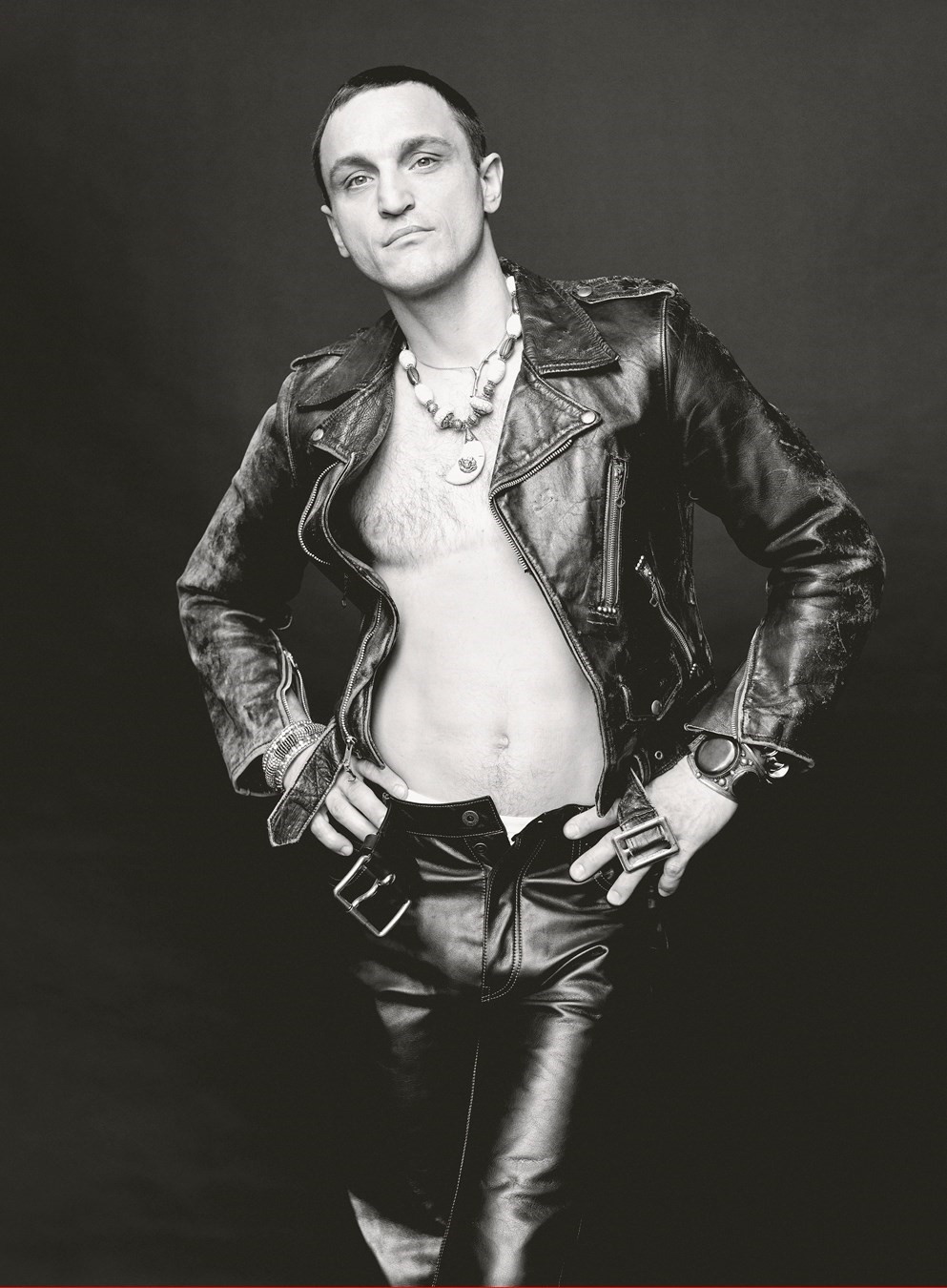

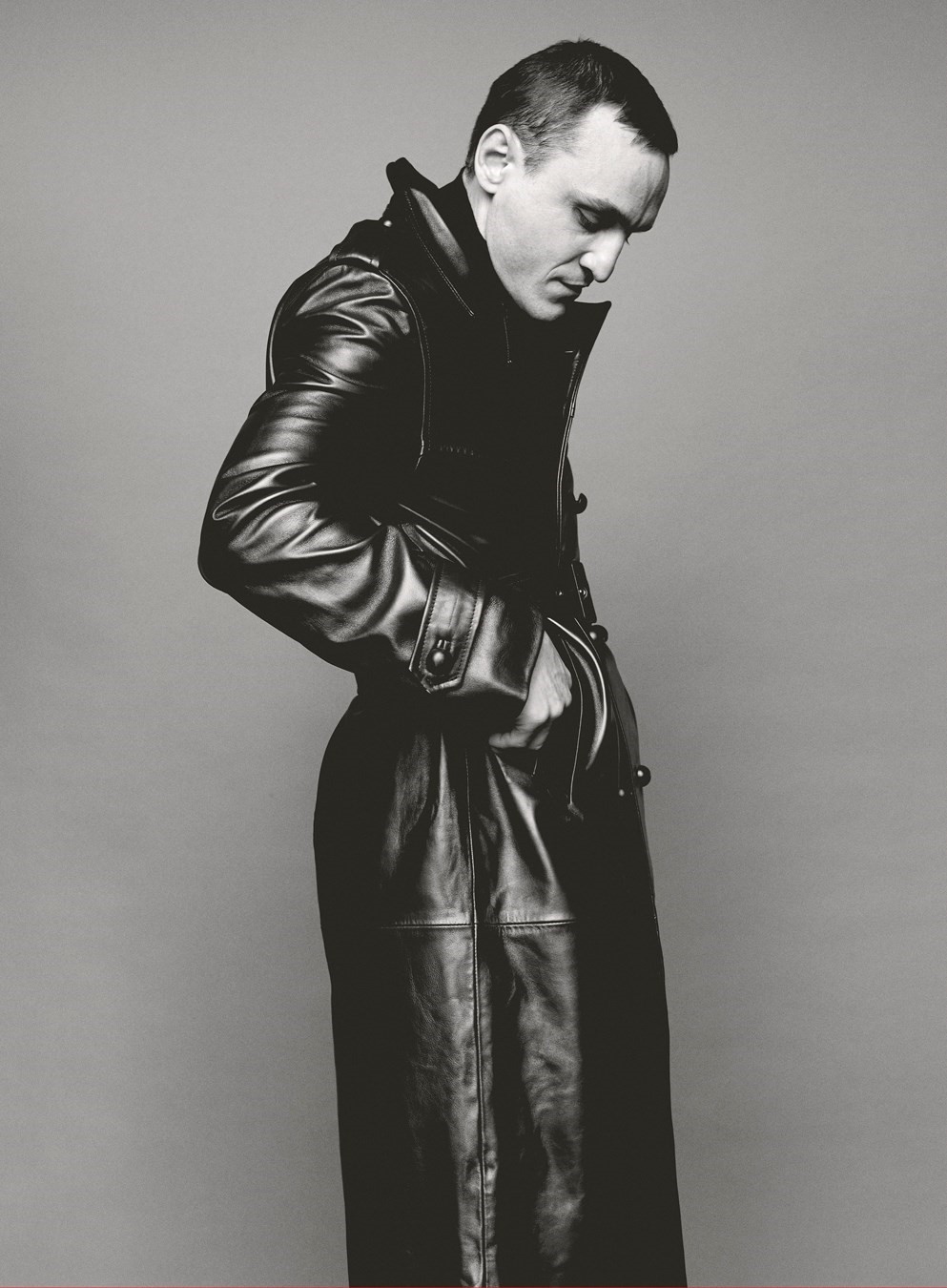

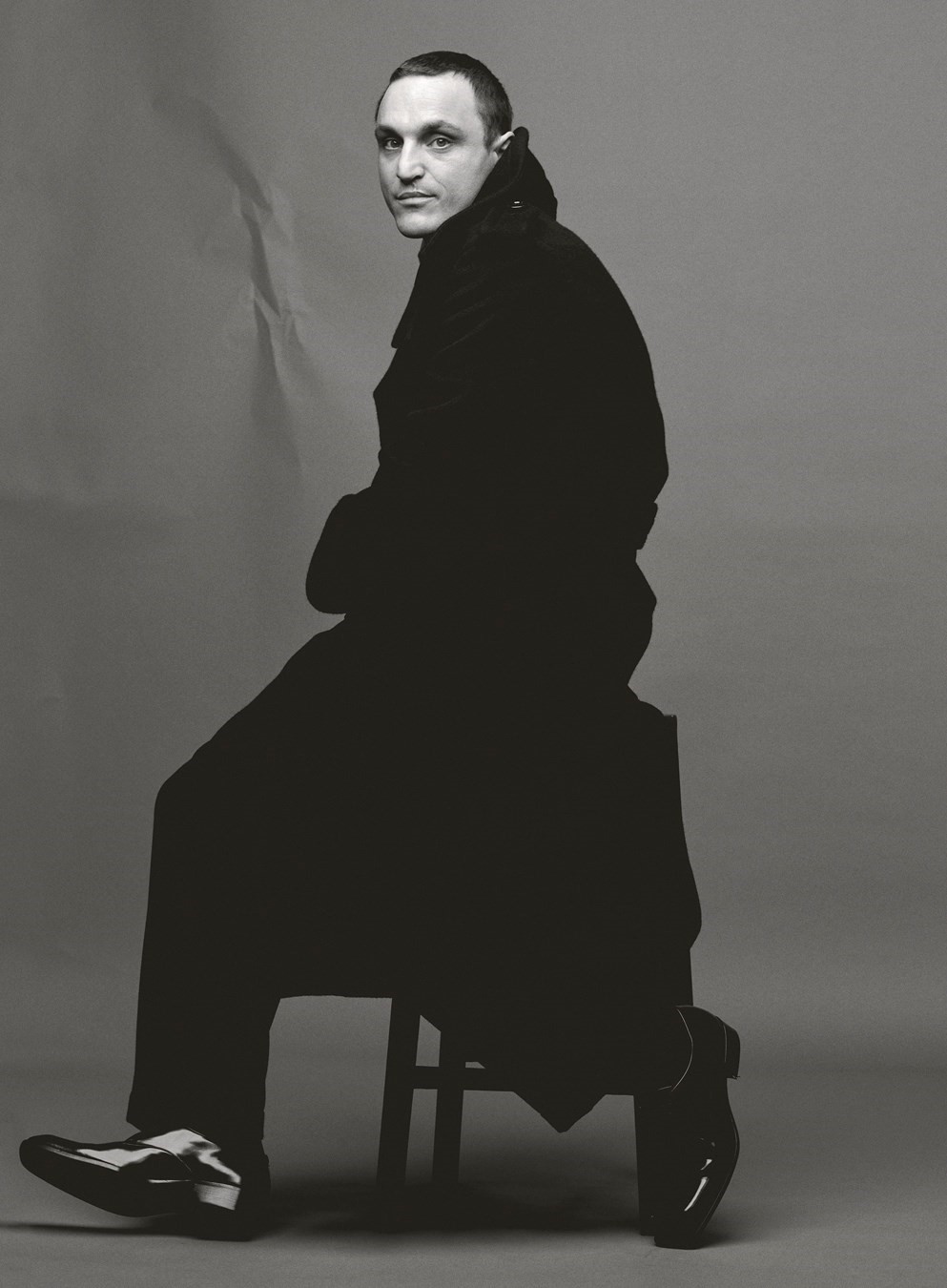

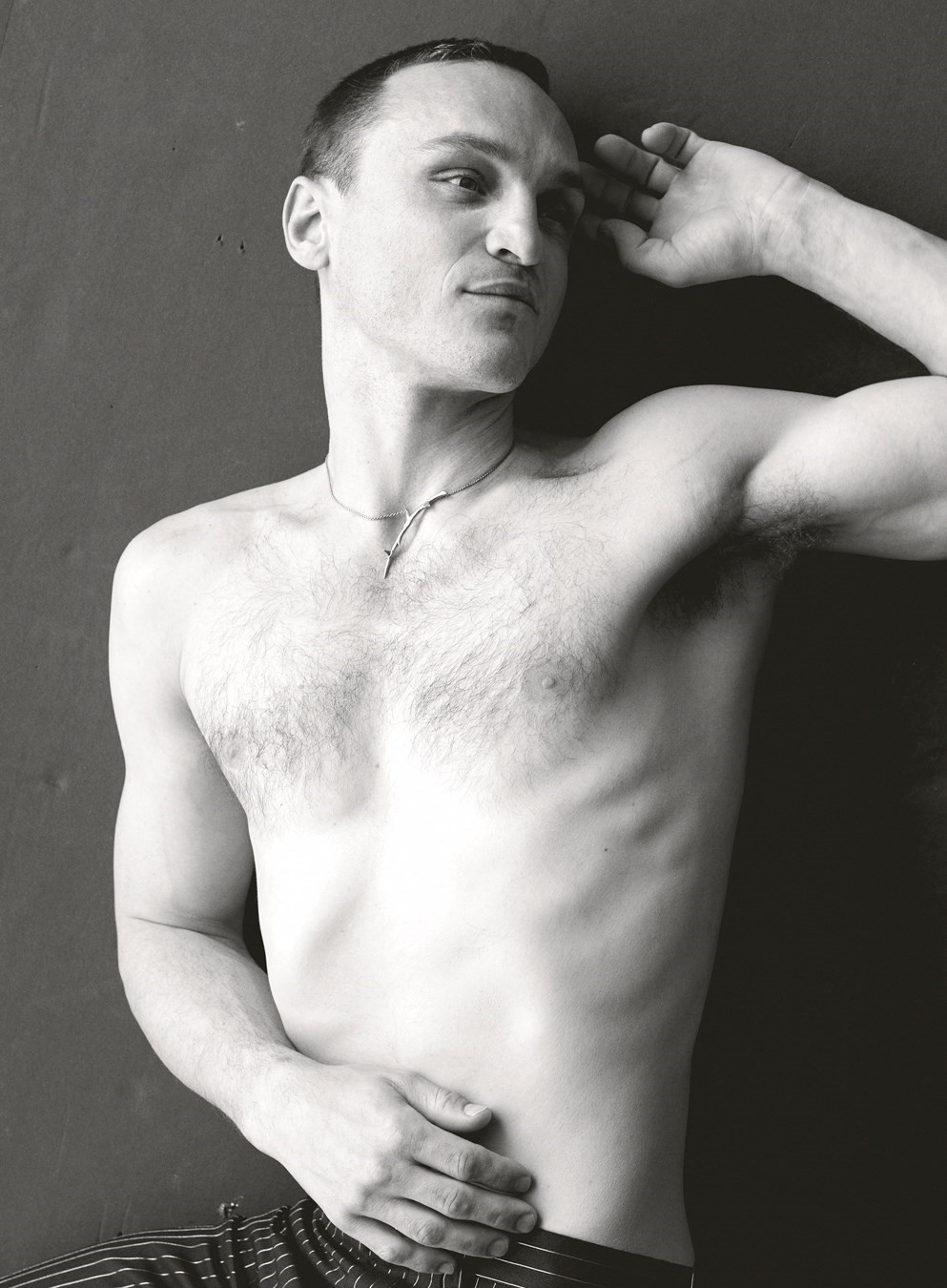

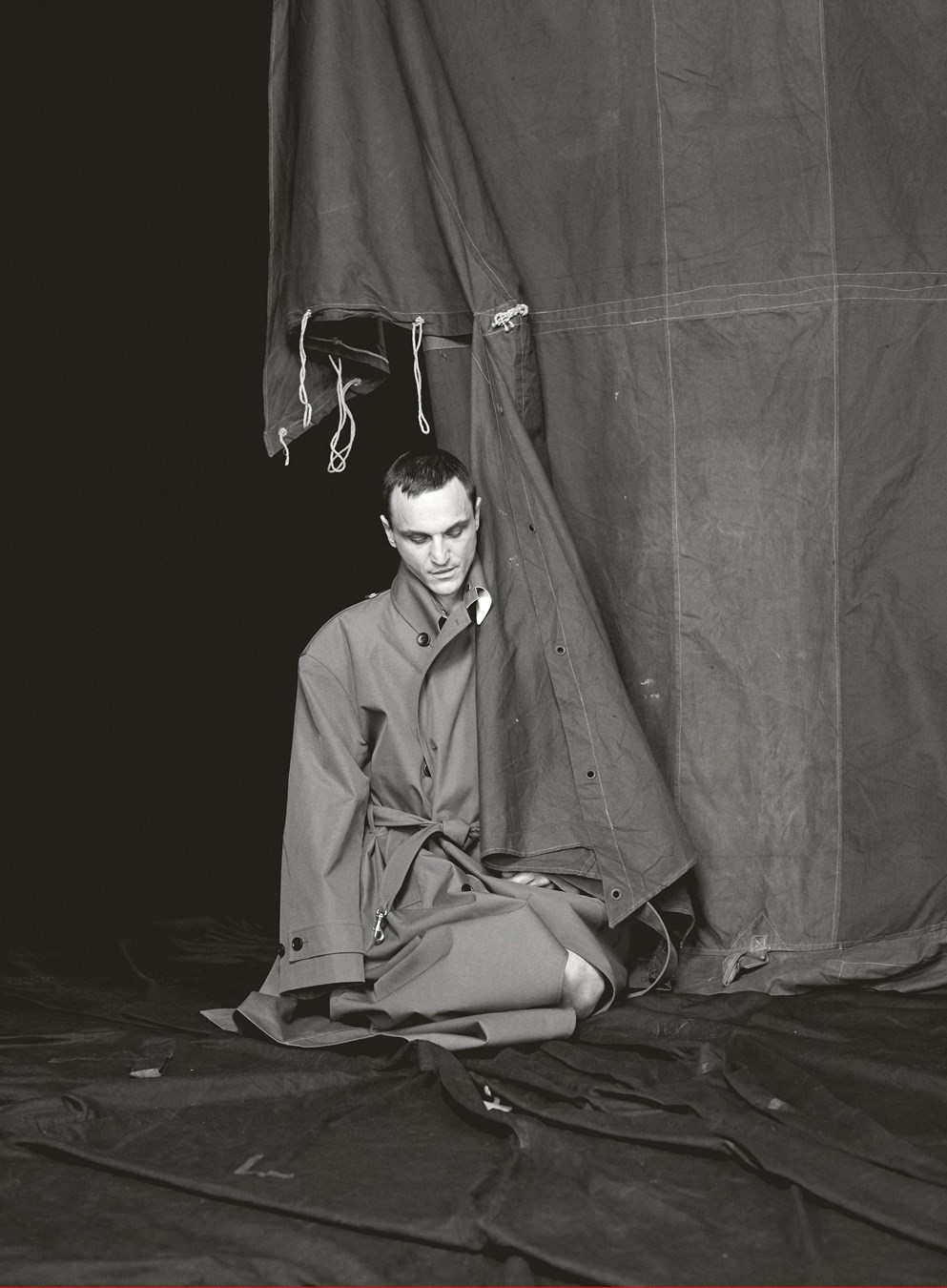

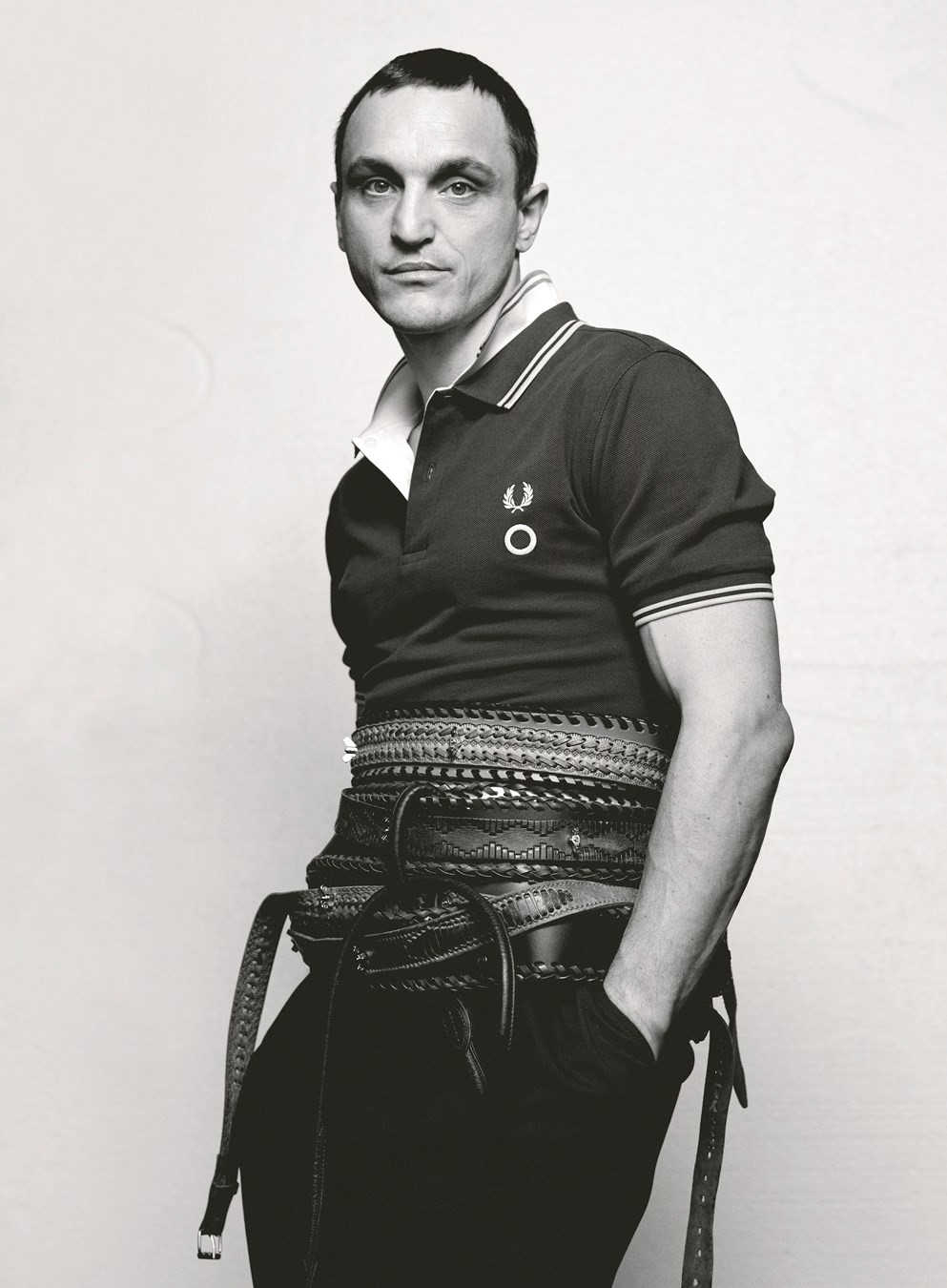

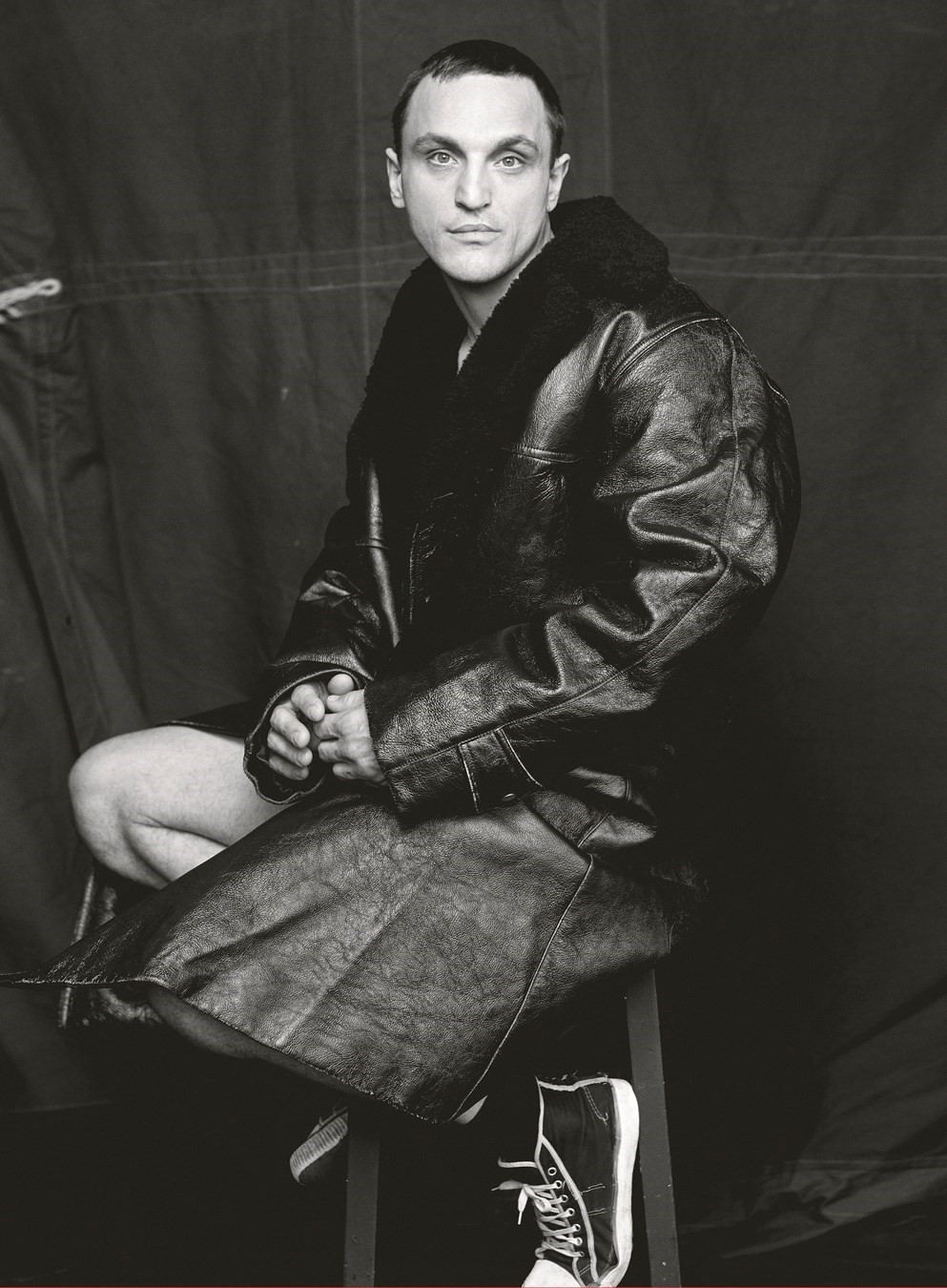

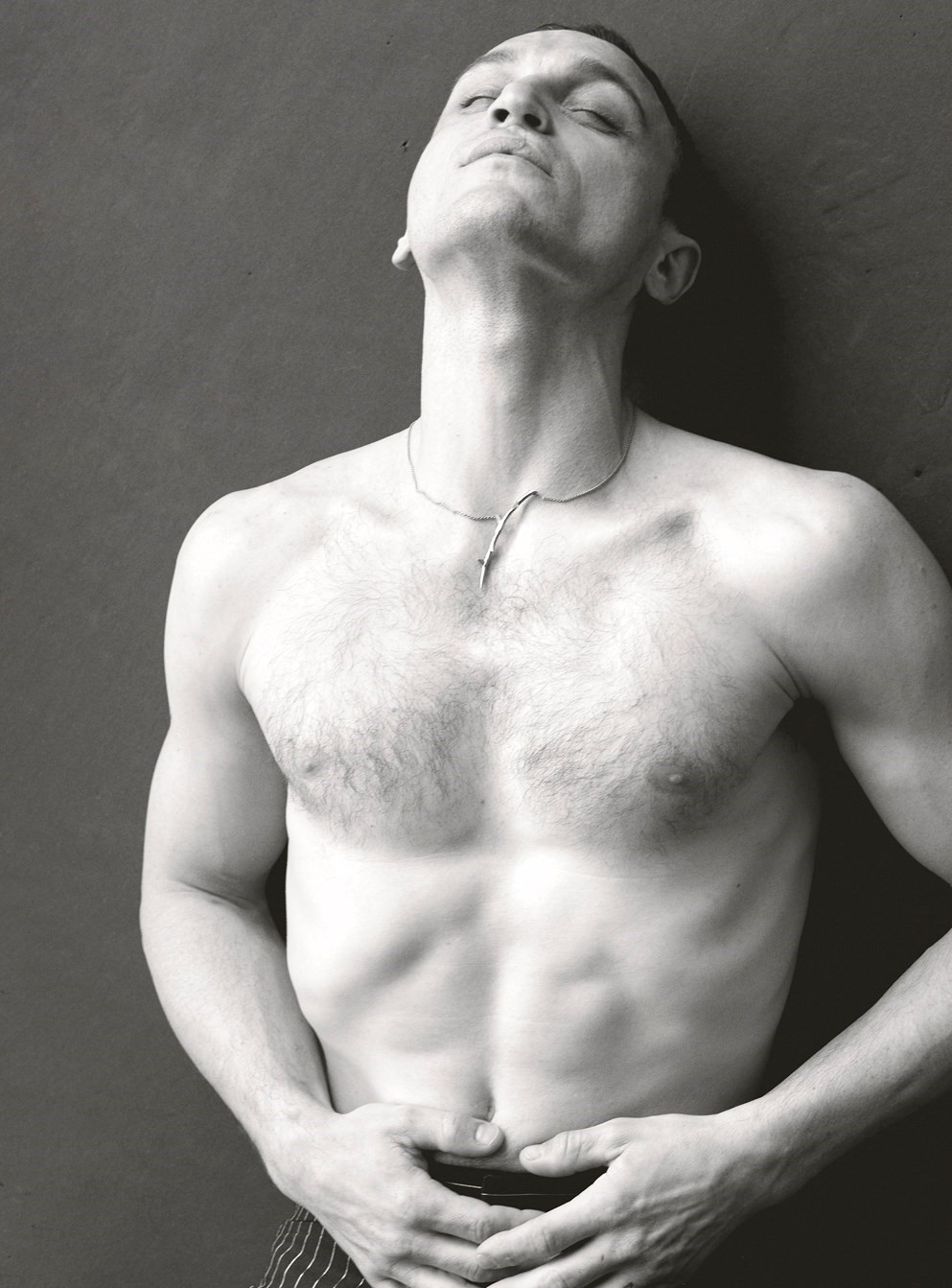

I step downstairs and spot him across the street, leaning nonchalantly against a white van. The actor, known for his roles in Passages (2023), Great Freedom (2021) and Transit (2018), greets me with a warm smile and a tight hug. He’s dressed in leather cargo shorts cut above the knee and a loose black-and-white shirt printed with seals, the top three or four buttons undone, exposing his chest. His shaved head highlights his handsome, birdlike features, which are offset by a pair of wraparound sunglasses.

As we climb into the van, I notice a mattress in the back, devoid of bedding and with two large Rimowa suitcases stuffed in front of it. Rogowski tells me he’s lived in the van while filming his last four movies. “I love being part of the film crew during the day,” he says as we head out of Friedrichstadt, joining a shoal of early morning commuters. “But then I love to disappear overnight and not be trapped in the hotel with 50 other people and see them all at breakfast in the morning. Instead, I can listen to some Bob Marley and have some time to myself … It’s very nice.” He gestures toward the mattress. “And very cosy. I have some fur blankets, and there’s a cooker in the back that you can pull out and cook with.”

Fans of arthouse cinema and German film have likely followed Rogowski’s work for years. He has built a reputation for playing a smorgasbord of characters living on the margins – or outside the conventions – of mainstream society, from a gay man repeatedly imprisoned under post-World War II Germany’s anti-homosexuality laws in Great Freedom to a Yenish street performer whose children are taken away as part of a 1940s Swiss “re-education” programme in Lubo (2023) and, most recently, a drifter who befriends a troubled 12-year-old girl on a housing estate outside London in Bird, the new magical realist film by American Honey director Andrea Arnold, set for release this autumn.

In each of these roles, Rogowski captivates audiences with his magnetic and mysterious presence, drawing from a complex – perhaps chaotic – inner world. His performances are imbued with an implicit, impish instability that has earned him critical acclaim both in Germany and internationally. In 2018, he won a Lola (Germany’s equivalent of an Oscar) for his performance in In the Aisles, opposite Anatomy of a Fall and The Zone of Interest star Sandra Hüller. But it was Ira Sachs’ film Passages that caused his fame to reach new heights in the anglophone world; in it, he plays a filmmaker who cheats on his husband with a woman in Paris. His portrayal of Tomas was as marked for its outrageous behaviour as it was for its outfits (perhaps one of the reasons he’s now a friend of Saint Laurent). In one particularly memorable scene, Rogowski sports a skintight, see-through crop top adorned with Chinese dragons in a (successful) attempt to seduce his husband, played by Ben Whishaw.

Rogowski’s own life echoes the three-way plot of Passages, beginning in Swabia, in south-west Bavaria. “My parents have been together since high school, and my biological father was a friend of my social father at university. They had an intense ménage à trois for a few months, and I’m the result,” he shares as he puts the foot on the pedal and careens down a broad Berlin boulevard. “I grew up with my mum and my social father, while my biological father was more like an uncle-father, an adventurer-father, someone I’d go to the mountains with.”

He and his six siblings enjoyed a middle-class upbringing – his fathers are both doctors, and his mother is a midwife – but Rogowski struggled in school. “I was always close to failing,” he admits. “They would let me advance to the next class because they knew I was capable in theory, but I had ADHD. Later, as a teenager, I became very depressed and smoked a lot of weed. I fell into a circle of hip-hoppers, spending most of my time sitting on couches, smoking huge bongs, and wearing baggy pants that would hinder my walk – to an absurd degree. I had to hold my pants with one hand and my backpack with the other.” During this period, he listened to a lot of Tupac and Nirvana, pinning a poster of Kurt Cobain above his bed. The poster featured the title of the band’s 1993 song, I Hate Myself and Want to Die – a sight that understandably worried his mother.

Today, we’re going bouldering – a favourite pastime of Rogowski’s – but first, we have some errands to run. We head up to The Good Store in Reuterkiez, where Rogowski plans to consign some clothes. He’s been gifted plenty of late, and wants to offload some items he no longer wears. After greeting the shop owner, he starts pulling out pieces from his Rimowa suitcases: loud shirts, louche suits, luxury shoes. They negotiate prices for a while before we head back to the van and drive to a bouldering gym in Neukölln.

Rogowski comes to Bouldergarten – or one of the other bouldering clubs scattered across Berlin – about four times a week; the sport has surged in popularity in recent years. He also climbs in the mountains with friends. It’s another form of therapy for him. “Me and my friends are addicted to climbing,” he says as we cross the car park and enter the gym. “I spend maybe two or three months a year on real rock and in between I train on a plastic wall, doing finger training and core training and preparing for the time on real rock. Also, I bought this van because of climbing. You live on a little campsite in the mountains and cook under the stars – it’s just you, your friends, the mountains and the stars. It’s quite romantic.”

“It’s funny, because now we’re in a boulder gym and I think my love for the mountains also has to do with me looking for a father figure in life,” he muses. “But the father figure could also be me taking care of my inner child.”

“But as a German, in the world of cinema, you can only be a Nazi or a villain ... I can assure you that most offers are related to the Holocaust and it needs to be an incredible project for me to engage with those kinds of roles” – Franz Rogowski

It’s hot inside the gym. A former factory, the space is illuminated by large paned windows; bouncy, blood-red mats cover the floor, while brightly coloured holds adorn the walls like big blobs of plasticine. An assortment of climbers scale the walls around us, while techno pulses gently in the background. “It’s a queer-friendly gym,” Rogowski notes, gesturing to the diverse crowd milling about us.

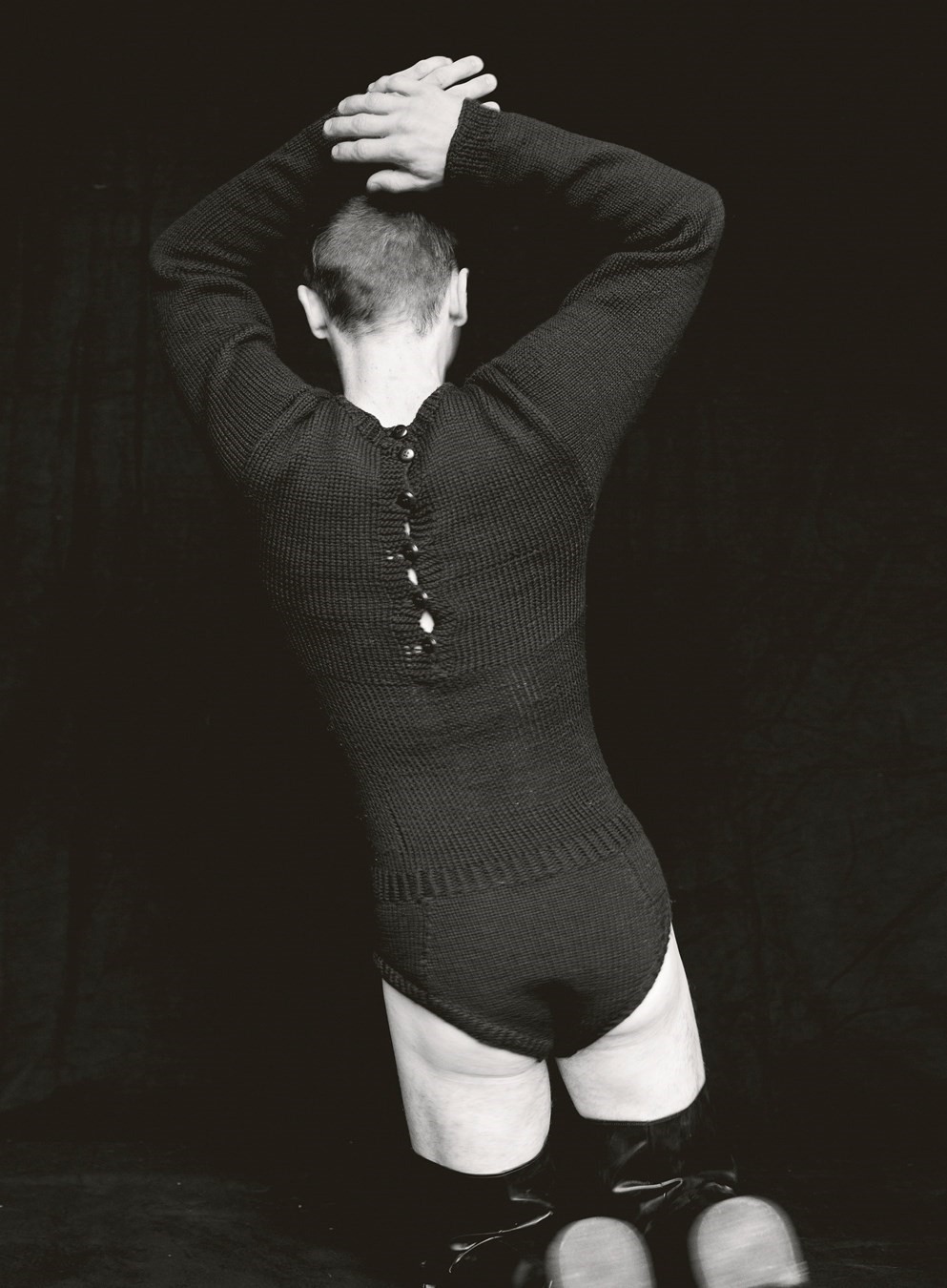

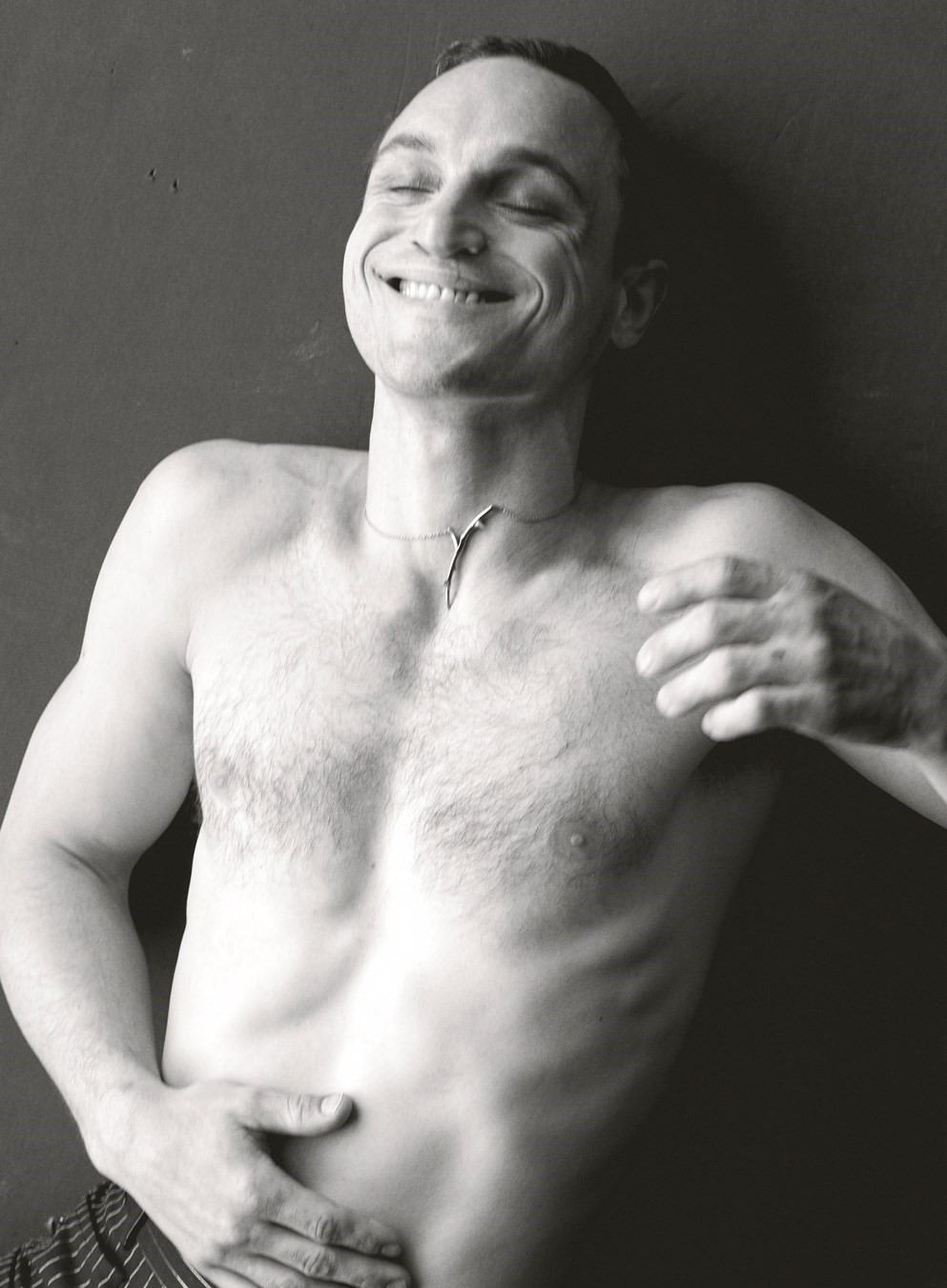

As we approach the climbing wall, Rogowski – now clad in a scruffy T-shirt and pair of short Adidas shorts – explains the significance of the different coloured holds, each indicating a unique route with varying levels of difficulty. He points out an easier path and demonstrates, gracefully manoeuvring from hold to hold like a spider monkey. His movements are slow and meditative; he presses his body against the wall, pausing at each grip to take a breath before continuing upward. It’s clear why this practice serves as an effective mindfulness exercise for him.

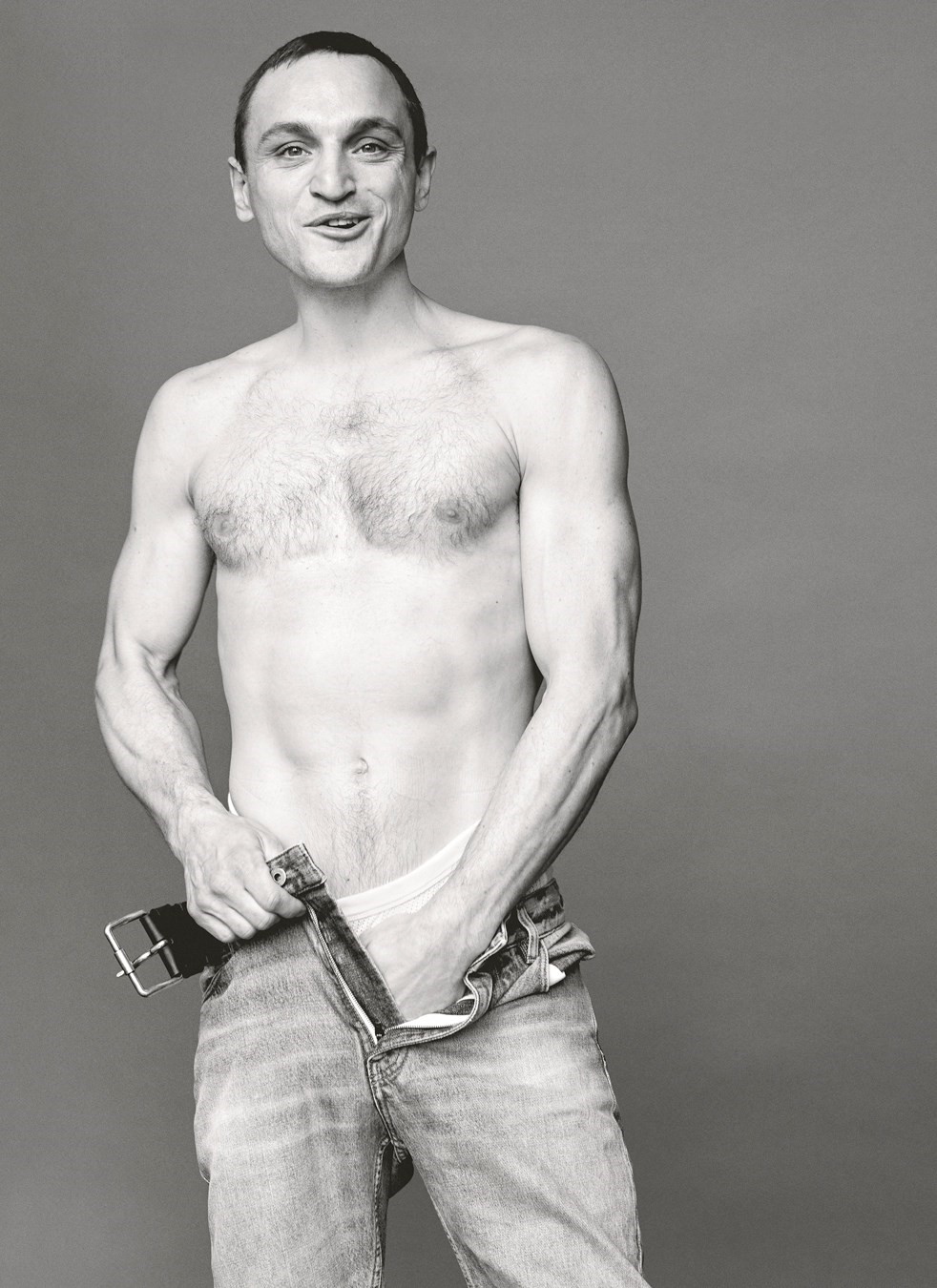

It’s also hard physical exercise. After about an hour and a half of clambering up walls, we move upstairs to another section of the gym where Rogowski straps on 50 kilograms of weights around his waist and begins doing pull-ups – using only his fingers. He holds each position for five seconds before repeating the exercise. His focus is intense as he looks straight ahead, breath held and then expelled in a controlled puff. His T-shirt rides up as he does this, revealing his muscular arms, taut with effort, while his legs dangle loosely below.

Rogowski has endured a lot to fully inhabit his roles, with Great Freedom being particularly taxing. “I felt really bad during that shoot,” he shares in a break from the pull-ups. “I lost 20 pounds, which for me is quite a lot and really put me in a bad situation. I had zero libido for four months and 100 per cent depression all day. Then, when Covid hit, I had to lose all that weight again for the concentration camp scene. I’d gained 30 pounds and then I had to lose it all again. I’m not sure what damage it did to me.”

Rogowski’s physicality is a key part of his performances – just watch his improvised dance to Sia’s Chandelier in Michael Haneke’s Happy End (2017) on YouTube for proof. This connection to movement began in his early twenties when he moved to Berlin and enrolled in a dance academy. He flirted with a variety of practices during these early days in Berlin, a city ripe for exploration and experimentation. He dabbled in slacklining and contact juggling – manipulating a glass ball in contact with the body – as well as ballet. Those years were filled with trial and error; he attended art school, played saxophone in subway stations, worked briefly as a bike messenger, and even trained as a physiotherapist. “I really tried many, many things.”

Rogowski also spent time at a clown school in Switzerland when he was 18. However, his experience was cut short; he had broken his wrist the previous year, and the rigorous training – six hours a day of stretching, acrobatics, dancing, juggling and breakdancing – aggravated the injury. He flew home to Germany for surgery but forgot to inform anyone at the academy. When he came back six weeks later, the teachers were upset and decided to expel him, despite his passing all the exams. Devastated, Rogowski recalls breaking down in tears upon hearing the news. Not even a letter from his mother to the academy’s director could change their decision. “I’ve always failed in institutions,” he reflects sadly. “I failed in high school – I have no high school degree, I have no acting degree, no dance degree, nothing.”

“Often, when I look at actors’ performances, what I see is an open trauma covered in a costume. People think, ‘Wow, that’s so intense,’ but this is a really intense person. It’s a person in pain” – Franz Rogowski

Rogowski later joined a dance theatre company, which was more butoh than ballet, he says, and involved “throwing himself around on the floor” and “being a crazy monkey in the mud”. However, he soon felt trapped in that role. “[As a dancer] in theatre, you’re often just a colour or an ambiance in the actor’s psychological world,” he reflects. “For years, I worked hard in the background, embodying this wild creature that supported the plot, like a fog machine in the background.” A back injury ultimately sounded the death knell for his dancing career.

He continues to grapple with chronic back pain and has tried everything – from therapy and painkillers to opioids prescribed by doctors – without success. Climbing is one thing that offers some form of relief. There’s still something of the wild creature in Rogowski’s work as an actor – it’s evident in his role in Passages. His character Tomas is a flagrant narcissist, who is as charming as he is cruel. When he cheats on his English printer husband, Martin, with French schoolteacher Agathe (Adèle Exarchopoulos), his innocent bewilderment at Martin’s disinterest in the affair is comical. In fact, Tomas’s emotional insensitivity (and manipulation) borders on the absurd throughout the film (it elicited audible reactions from the audience when I saw it in the cinema). He’s that toxic guy you know is toxic yet can’t help liking anyway.

“I needed to make Tomas innocent,” Rogowski explains, “because otherwise he would just be a terrible asshole. I think if you love and hate him at the same time, it’s a bit more interesting for you as an audience, emotionally.” In real life, Rogowski shares some of the charm and chaos of Tomas, but instead of the cruelty that accompanies it, there’s a kindness. When we part, he surprises me by gifting me the red Tsumori Chisato jumper from the dinner scene with Ben Whishaw, saying he felt like it belonged to me.

Rogowski’s untamed quality also shines through in Bird. Like a contemporary Charles Dickens or a magical realist Ken Loach, the film is a beautiful but brutal portrayal of deprivation and dysfunction in modern-day Britain. Set on a housing estate outside London, Rogowski portrays a peculiar stranger called Bird, who appears out of nowhere to help a young girl named Bailey (Nykiya Adams) deal with her inept, often inebriated father, Bug (Barry Keoghan). Filmed across various locations in north Kent, Rogowski says he was taken aback by the poverty he witnessed there, a side of the UK he had not encountered before. While it’s not an easy watch, Rogowski’s performance gives the film some levity; Bird is innocent, playful and just plain curious.

“One could think that [the film is] poverty porn, but it’s not, because Andrea really knows that world,” he explains. “It’s where she grew up. It’s her experience. These are her colours, and that’s why she’s absolutely entitled to paint with them.” The same is true for Barry Keoghan, whose mother struggled with drug addiction and passed away when he was just 12. He spent the next seven years in foster care, moving between 13 different homes.

Despite his successes, Rogowski has a fraught relationship with show business and feels at odds with the German film industry in particular. “I haven’t made anything here for five years,” he says. “I feel somewhat detached from my home market. But as a German, in the world of cinema, you can only be a Nazi or a villain. I’m stuck in between those worlds now – 80 per cent of what I do is read scripts and not do them. I can assure you that most offers are related to the Holocaust and it needs to be an incredible project for me to engage with those kinds of roles.”

“It has become a bit lonely, my life. I sometimes wonder if it’s worth it, being this picky arthouse guy who always says no – it can feel a bit unproductive sometimes. It has left me a bit lonely, and I wonder if that’s the way I want to live” – Franz Rogowski

I’m interested in how Rogowski picks his parts – he’s played a lot of LGBTQ+ characters. I ask why he was drawn to them and what he thinks about actors who don’t publicly identify as queer playing queer roles. “I’m drawn to films by directors who write their own stories … Great Freedom and Passages are by directors who for years have written these stories, which are often deeply interconnected with their own life stories,” he says. “But I don’t feel that my private life or my sexuality necessarily guide the roles that I want to embody … And I don’t want to identify because I want to perceive myself as someone who is curious and also eager to discover new sides of myself that I don’t know yet. I don’t want to limit myself to a certain way of living or cinema.”

This desire not to limit himself makes sense in the context of Berlin, where your sexuality is less defined by your identity and more by the party you’re at that night. Sexuality is not fixed here, but fluid and free – that Rogowski would have this attitude, choosing his roles because of the stories rather than the sexual identities of the characters, in a way that is undiscriminating and unencumbered, is unsurprising.

Once we finish with bouldering, we move to the yoga mats to stretch, beginning with my daily routine followed by his. While demonstrating a variation of the cat-cow pose, with our heads down and backs arched, he catches my eye and grins. “This is good for other things too,” he says with a twinkle in his eye. I laugh and say I have no idea what he means. We do a variety of stretches and he shows me some new positions, at one point applying some pressure to my glute to show me where I should be feeling the tension.

After our yoga session, we hit the showers and then hop back into the white van and head to Kitten Deli, an Israeli restaurant where Rogowski has reserved a table for lunch. We settle outside, where the lively chatter of fellow diners mingles with the sound of large droplets of summer rain beginning to fall. Rogowski orders hummus with pita, roasted aubergine and cauliflower, then resumes telling me about his life. “I’ve been reading scripts for 12 months, and I haven’t found one yet,” he says, dunking some pita bread into the platter of hummus and leaning back comfortably in his seat. Nearby, two young women have clocked him and keep stealing glances in his direction, though he remains blithely unaware of their interest.

As we continue to eat, talk turns to depression. “I really feel like there’s something chemically wrong with my brain,” he says with a hint of frustration in his voice. “I just wish I could somehow change gear. I don’t feel like I need to understand more about my trauma, because I know there’s trauma, and I feel I have agency, and I live my life – I’m just … I’m in pain,” he says, trailing off. “Often, when I look at actors’ performances, what I see is an open trauma covered in a costume. People think, ‘Wow, that’s so intense,’ but this is a really intense person. It’s a person in pain. And then people think ‘Wow, World War II,’ but it’s not World War II, it’s a trauma in a costume from World War II. It’s very interesting to look at acting that way.”

A few weeks ago, Rogowski met with his sister’s therapist, who generously offered him a couple of sessions before referring him to a colleague. He has sought therapy before – first at 16, when he was feeling suicidal (his parents said he could move out and even offered to cover his rent on the condition he attended sessions twice a week), and again at 22, when he saw someone for about a year before losing interest and discontinuing. “My [sister’s] therapist said I should take an antidepressant and just take the burden off my shoulders,” he ventures. “I’m not sure whether I should do it or not. There’s a stigma attached to antidepressants that is not helpful, but these are also strong medications and, somehow, I sell my problems – they’re part of my persona and the world that I create as an actor. So I’m hesitant to try.”

It’s a familiar story: depression as a creative aphrodisiac, the fuel of great art. How many artists can say that their work has drawn on their own hidden wells of sadness? Probably too many to count. “It has become a bit lonely, my life,” he continues, softly. “I sometimes wonder if it’s worth it, being this picky arthouse guy who always says no – it can feel a bit unproductive sometimes. It has left me a bit lonely, and I wonder if that’s the way I want to live.” It’s a strikingly vulnerable admission from one of the most compelling actors operating in the world of arthouse cinema today. His discerning taste in films and the projects he chooses set him apart from his contemporaries. Yet it’s only human to question one’s choices, especially when they come at a cost.

As our time together draws to a close, I reflect on the pain Rogowski carries within him, the wagon of sadness he pulls behind him. This has given his performances in Bird, Great Freedom and his other films an authenticity and gravity, but it’s a heavy burden to bear. He gives me a hug, gets in his van and drives off, and I’m left thinking about his effusive charisma, cheekiness and charm – but also about that weight and the connection between great art and deep sadness. Perhaps it’s another toxic relationship, one that many of us – Rogowski included – aren’t sure whether to break off.

This article features in the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from 31 October, 2024. Order here.