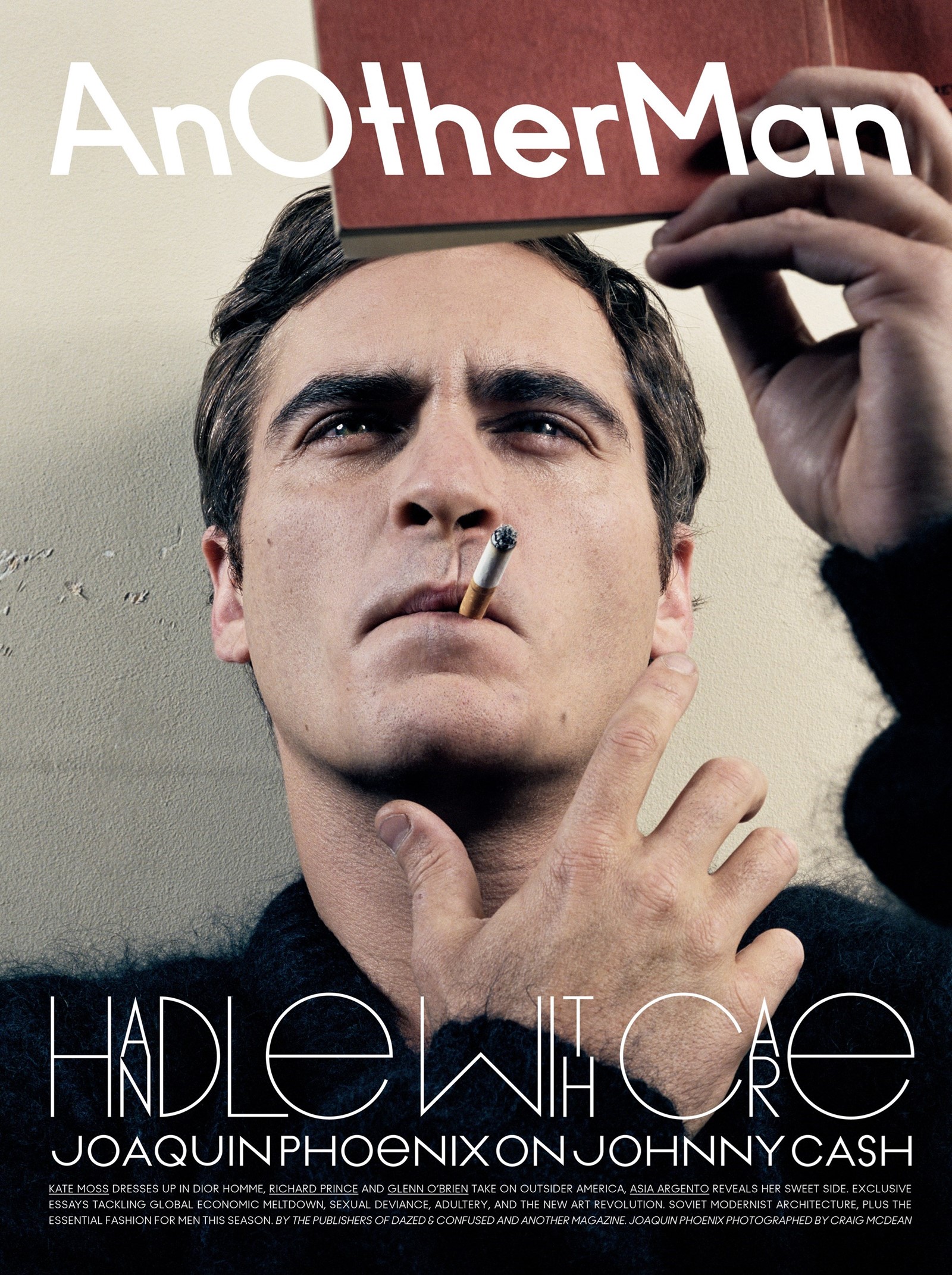

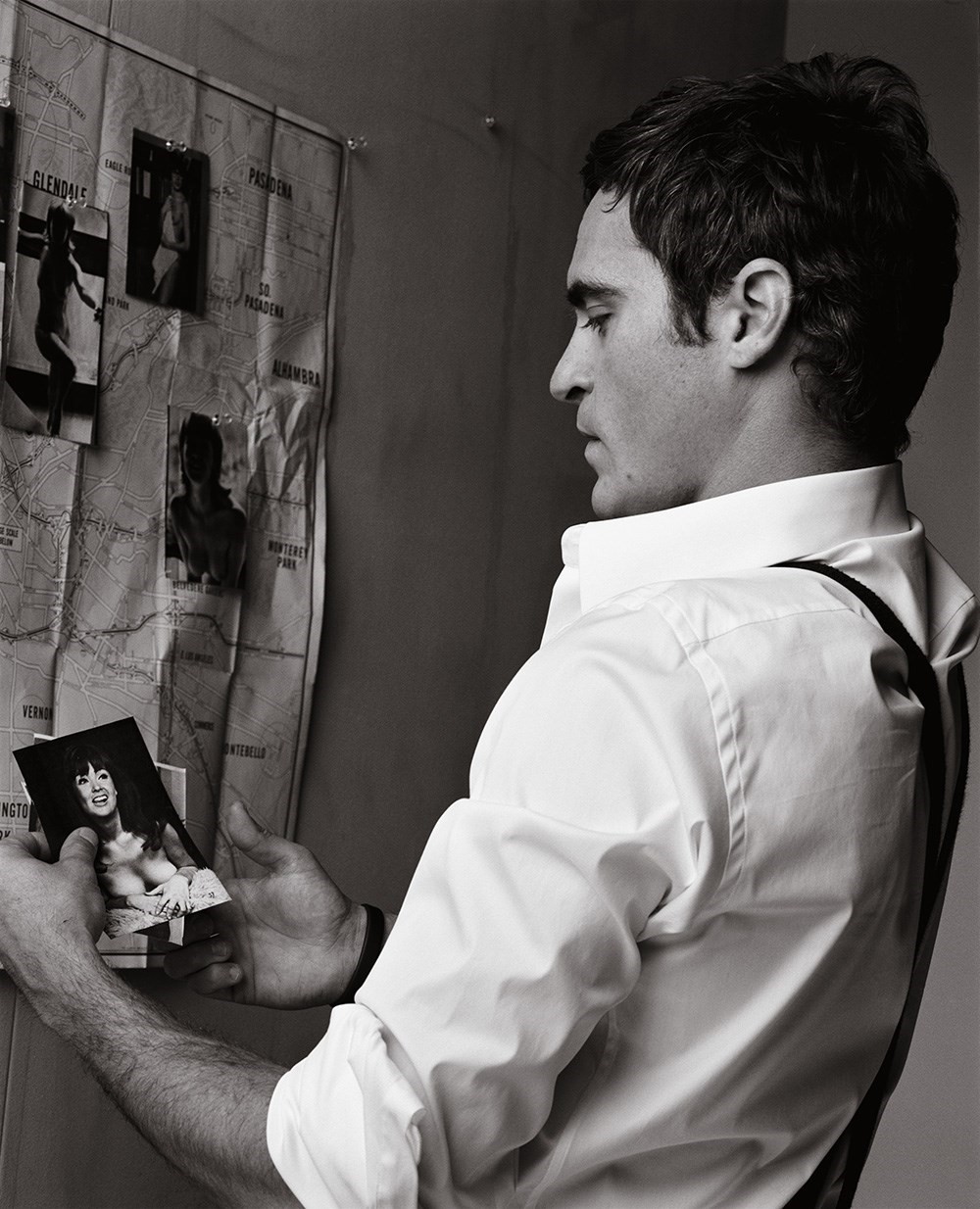

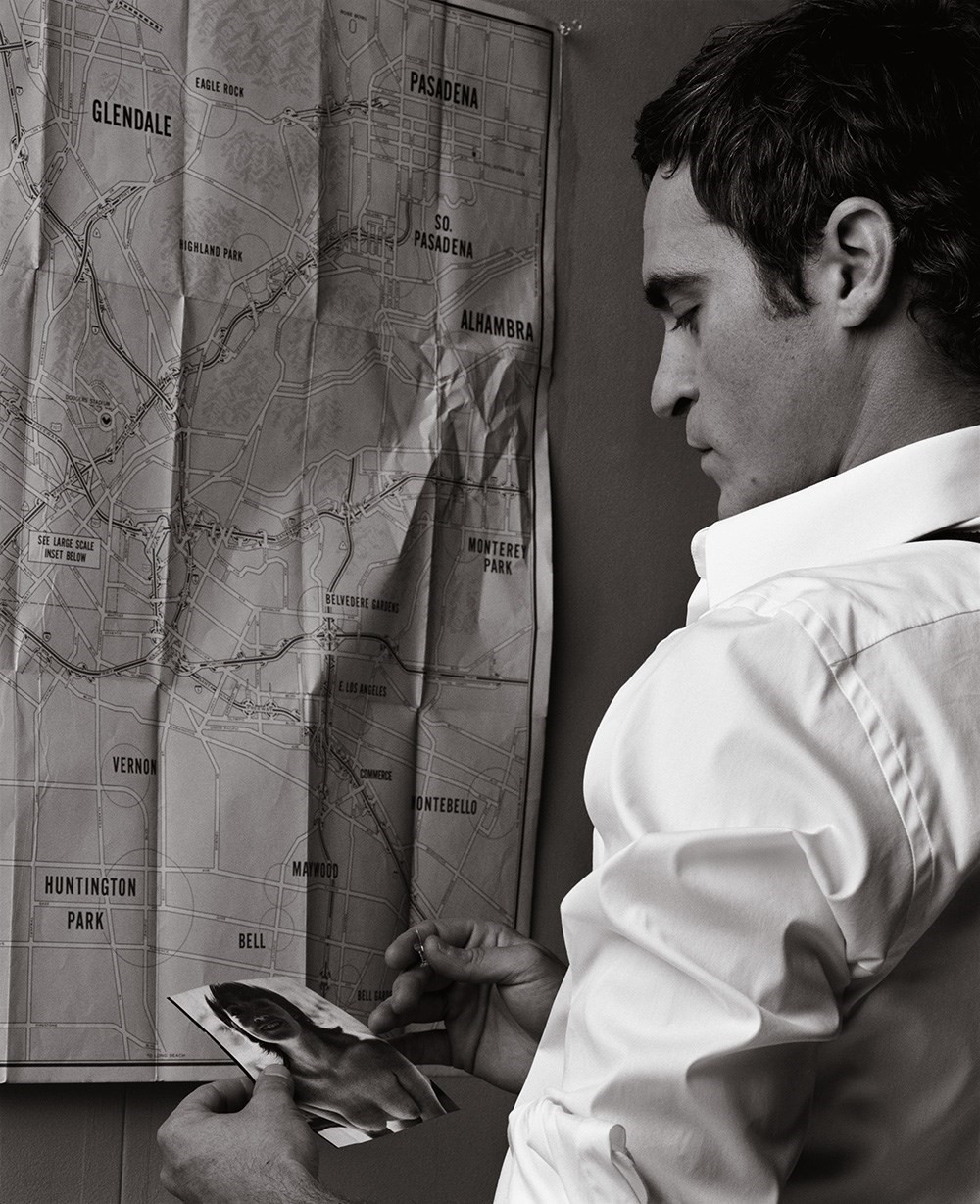

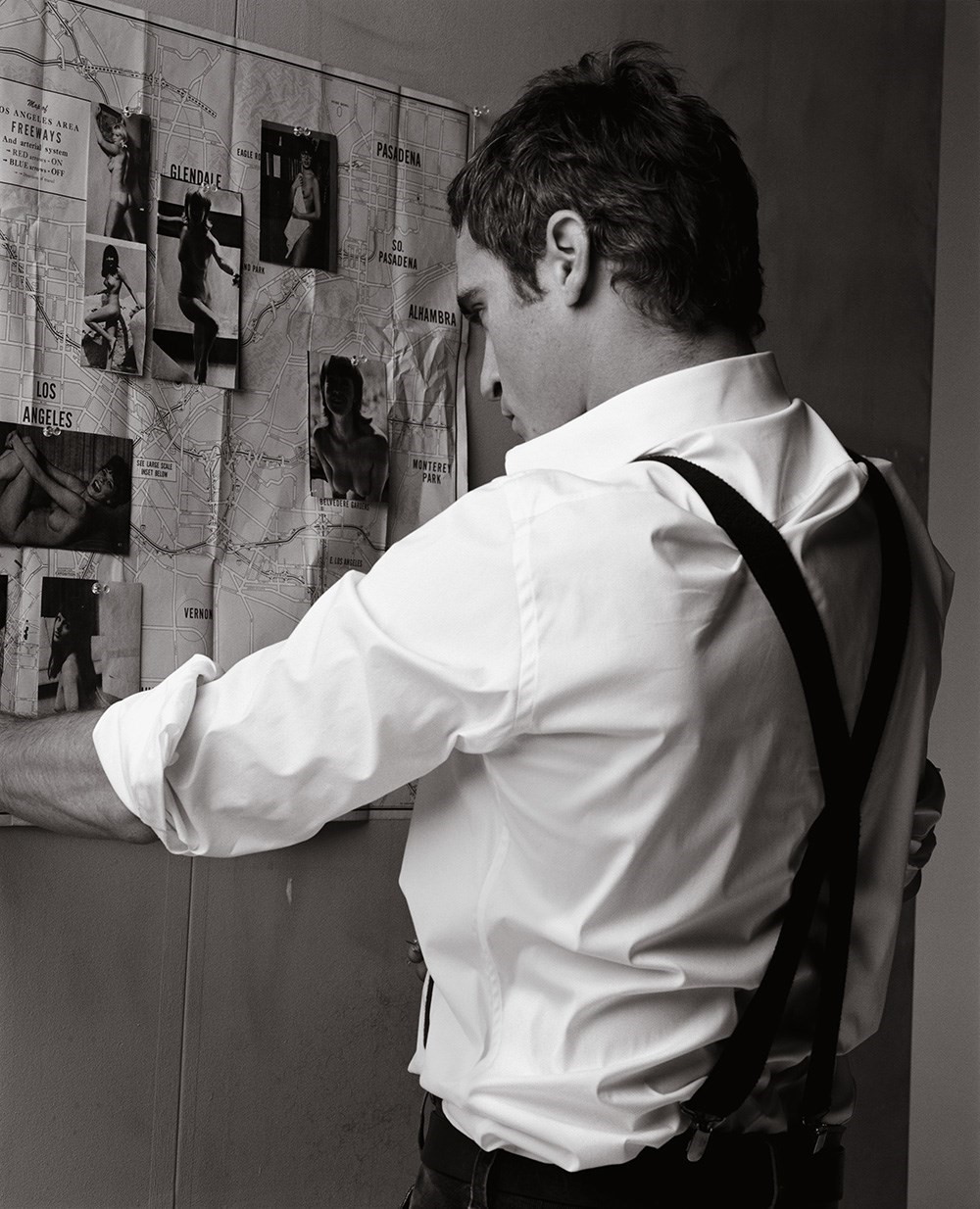

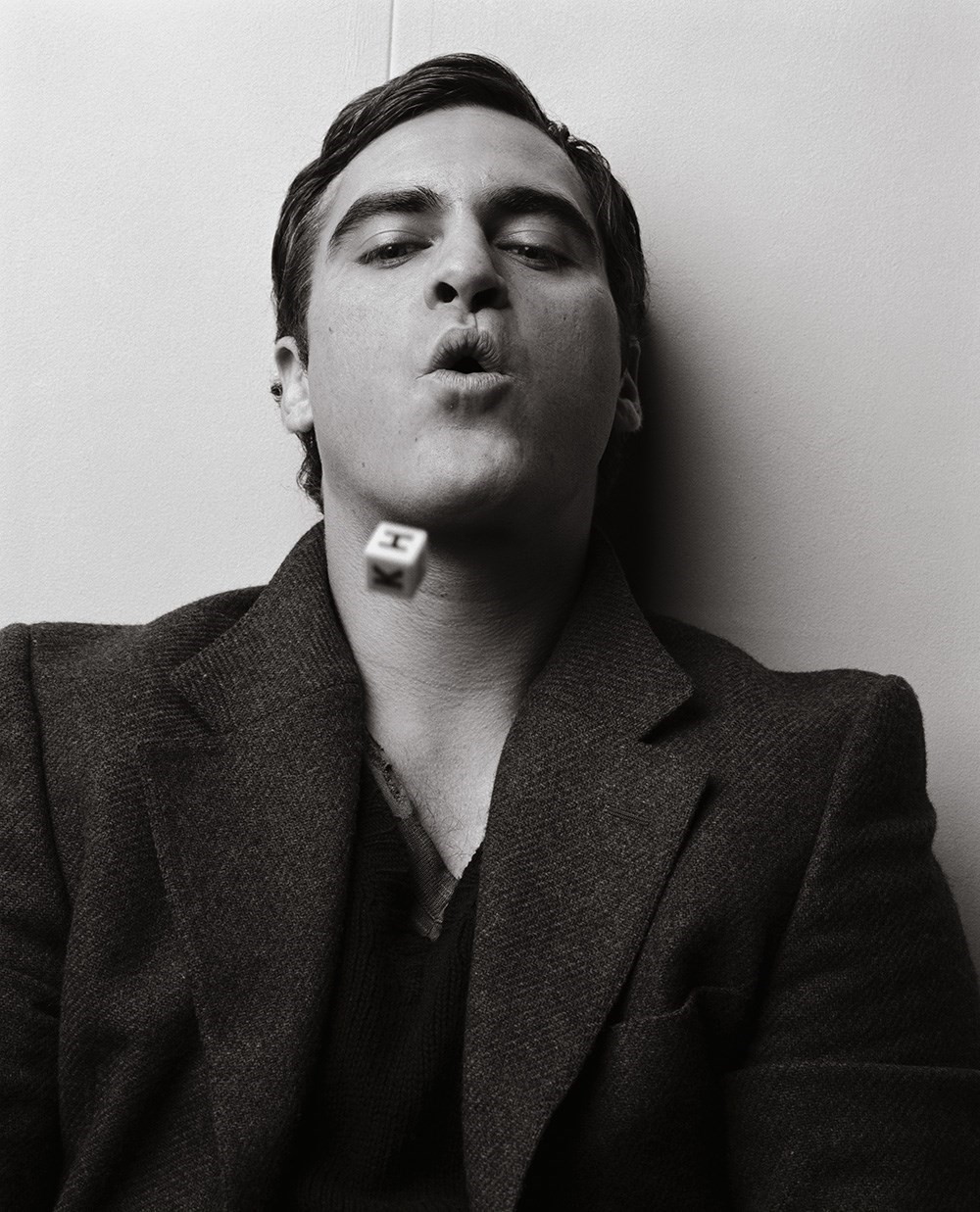

This story is taken from Another Man’s Autumn/Winter 2005 issue, the magazine’s debut:

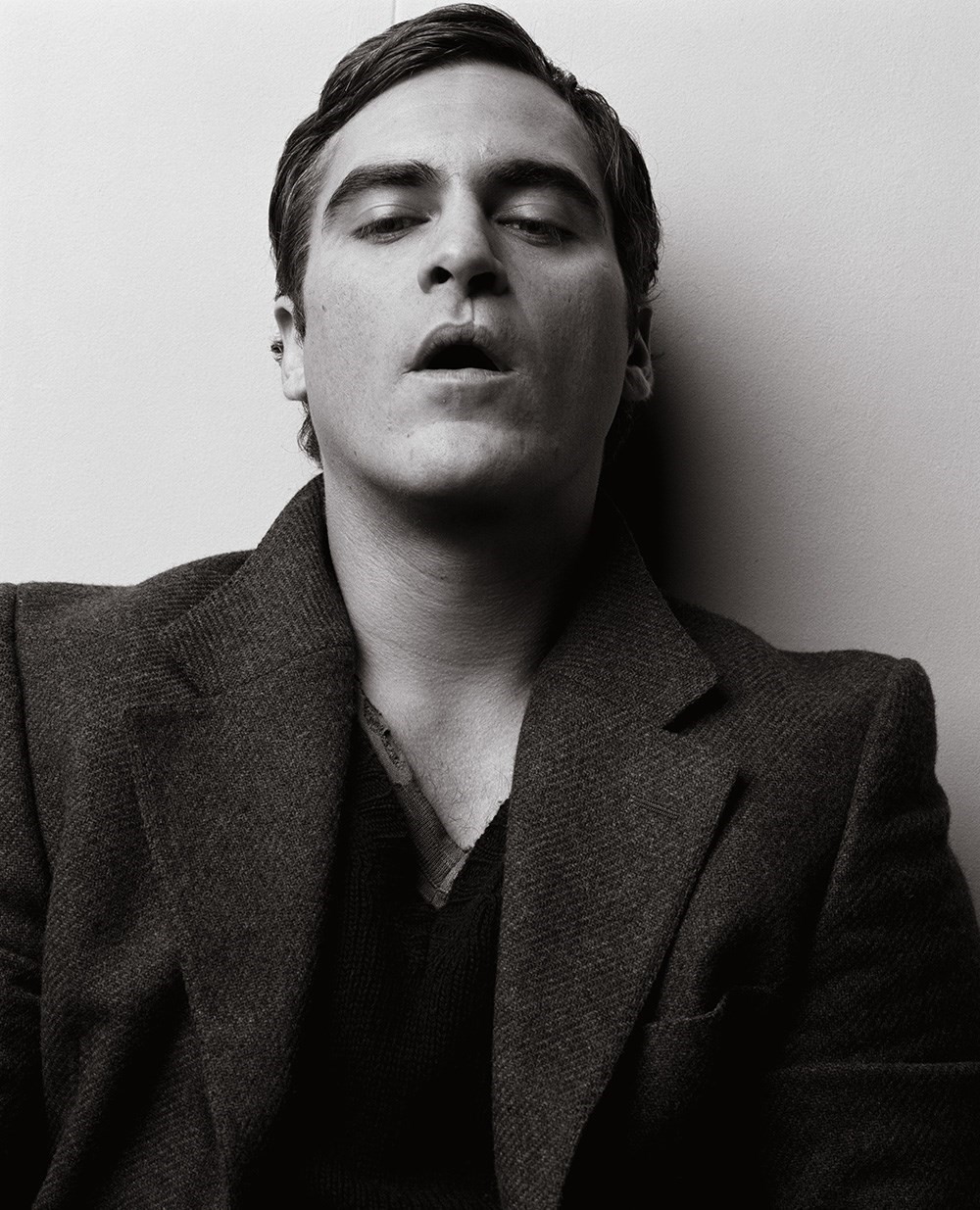

Joaquin Phoenix is dressed in black. Black shirt. Black trousers. Black shoes. He’s standing on a makeshift stage in a cavernous warehouse in Memphis, Tennessee. This old industrial building has been transformed to look like California’s stark and unwelcoming Folsom Prison as it was in 1968 – the scene of country singer Johnny Cash’s most famous gig, recorded for the live album Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. Several hundred tattooed heavies stand below the stage, loitering under the powerful heat of the lights. Each of the extras wears a prison uniform and each waits for Phoenix and the band that flanks him to do something, anything. Restless and rowdy, this motley crowd is fast running out of patience.

Phoenix leans into the microphone, guitar in hand, and effortlessly drawls, “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash.” Those four words throw the mass into a frenzy. Phoenix kicks his guitar into gear and launches into Folsom Prison Blues, drawing wild shouts from the crowd at the line, “I’m stuck in Folsom Prison and time keeps d-r-a-g-g-i-n’ on.” The actor further excites them by taunting the film crew between songs. He slyly calls out: “This show is being recorded for an album release on Columbia Records so you can’t say ‘hell’ or ‘shit’ or anything like that.” In Phoenix’s eyes, the crew are now the prison wardens. And he is the Man in Black.

“There was a real charge of energy in that room,” Phoenix recalls a year later. He’s thinking back to the key live scene that comes at the end of Walk the Line, the new biopic of Johnny Cash, which the actor made last summer with writer-director James Mangold. The film catalogues Cash’s rise to fame in the late 50s and 60s, following a rural upbringing in Depression-era Arkansas. It encompasses the singer’s struggle with drugs and booze; the increasing influence of his Christian faith; the break-up of his first marriage to Vivian Liberto; and his subsequent union with fellow country star, June Carter (played by Reese Witherspoon). Mangold’s film arrives amid a glut of movies about American rock legends. Gus Van Sant gave an elliptical insight into the death of Kurt Cobain with Last Days, and Todd Haynes (Velvet Goldmine, Far From Heaven) will soon shoot an experimental biopic about Bob Dylan. So experimental, in fact, that a whole series of actors – both men and women, black and white – will play Dylan. “This film is somewhere in the middle of those two things,” says Phoenix. “It’s midway between a conventional biopic and a completely abstract approach.”

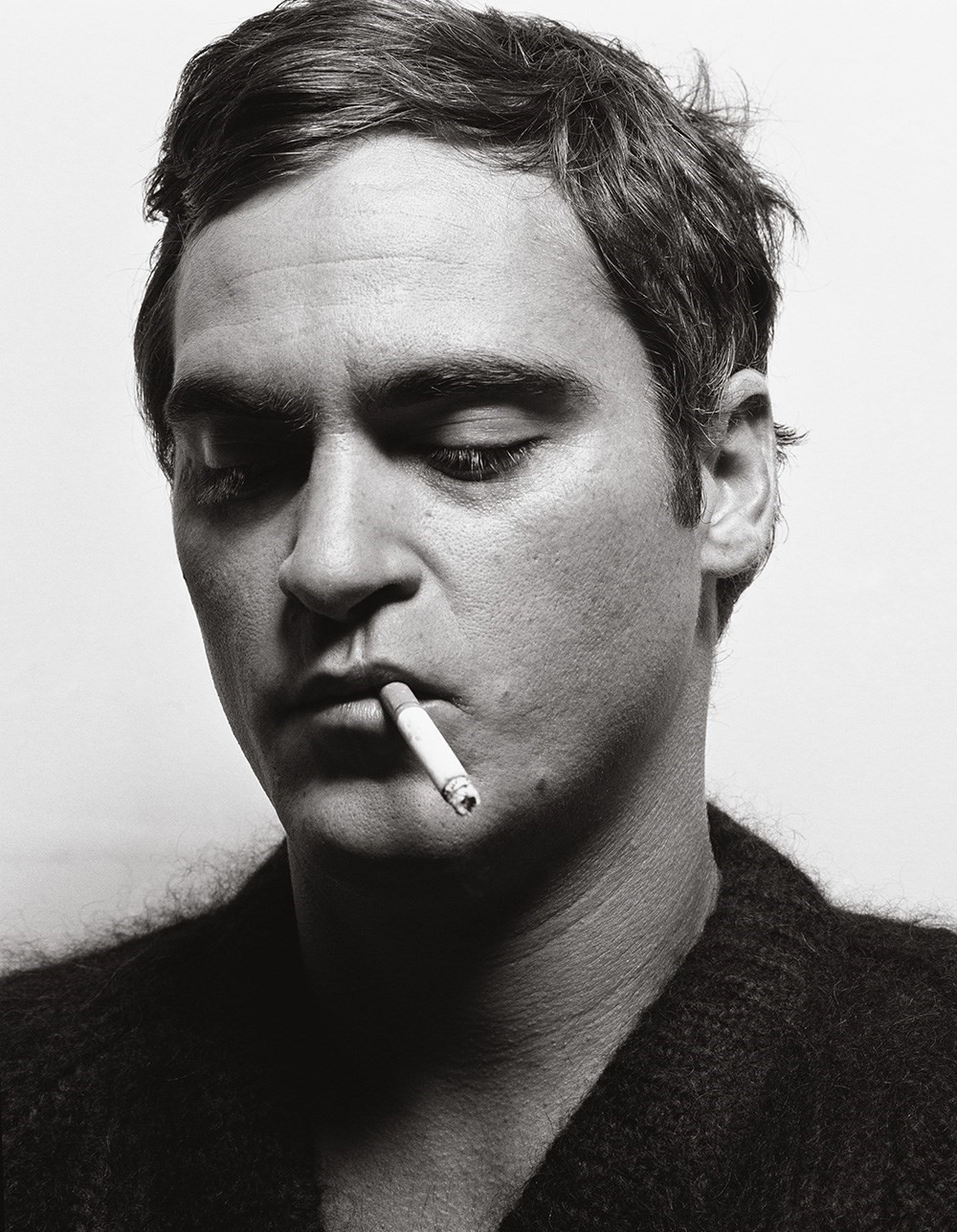

He is fired up today. The 30-year-old shows none of the conversational reticence or physical awkwardness with which he is sometimes tagged. He’s chain-smoking American Spirits in the garden of Los Angeles’s Chateau Marmont Hotel, and relishing the memory of the most intense film he’s made to date. When he talks of Cash he mimics the singer’s movements. When he quotes his lyrics he adopts the singer’s deep drawl. The more Phoenix talks, the more it becomes obvious that intensity is what this actor craves most. That and nicotine. He recounts in detail how he learned to play guitar and sing like Cash, right down to such specifics as mastering the same humming sound that Cash used to re-tune his voice between each verse of I Walk the Line.

“It was nice having so much to do,” he says. “Sometimes I think about things too much. I’m a super-thinker. I love to just fucking think. When you take so much on, you don’t get a lot of time to think. You just have to do.”

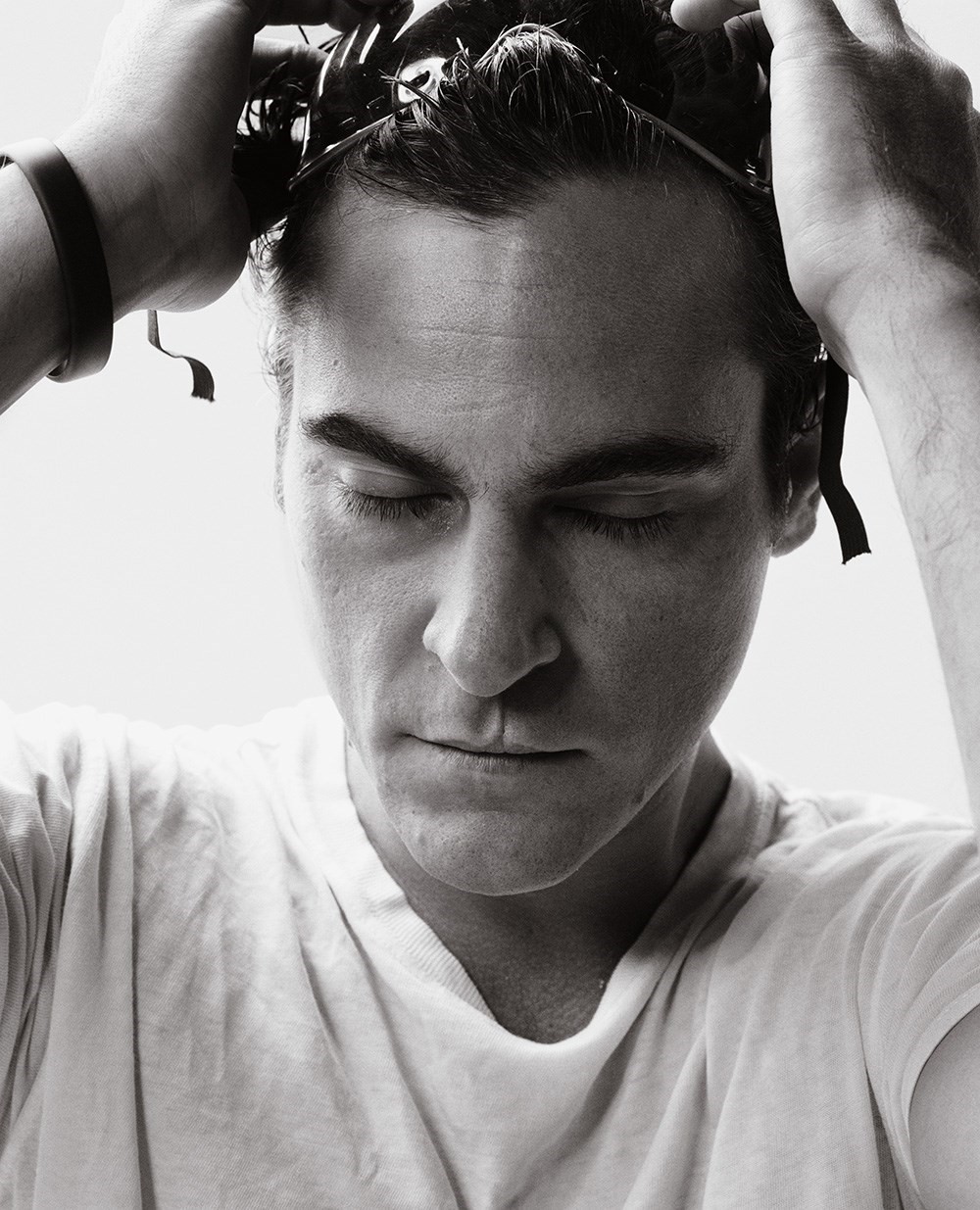

Walk The Line engulfed Phoenix’s life for almost a year. Along with it came the huge responsibility of playing a recently deceased musical legend. Phoenix needed to sing and play guitar exactly like the man himself, and to record a whole series of tracks with producer T-Bone Burnett before shooting even began. The experience was so intense that once filming was over the actor checked himself into rehab seeking treatment for alcoholism.

I ask Phoenix whether, psychologically, this was an especially difficult film to leave behind. At first he says nothing, he just grins as if to suggest the question only scratches the surface.

“Er, yeah,” he begins. “The hardest thing is going from six months of knowing what you’re doing everyday and having a clear direction, to suddenly cutting loose. There’s nothing. You feel abandoned. And this was the longest I’d ever spent working on something. Everything was about John. Everyday, all I did was read about or listen to John. It takes a few months to slowly start reintegrating. You start to remember, ‘Oh, this is what I like! This is what I do!’ At some point, being John just became natural to me. And you carry it with you in a such a way that other people are more aware of it than you.”

It’s not that Phoenix had suddenly turned into a helpless drunk or gained a drinking problem overnight. The problem crept up on him slowly. He just became aware that he was relying on alcohol to get him through the tedium of not working. “I wasn’t an everyday drinker. That’s what I thought an alcoholic was. But then I realised that’s not really what it’s like. The problem was that I didn’t feel connected to anything and I was leaning on alcohol to make me feel okay about that. That’s really what it was about. That’s when I realised that I needed to find a way to connect with myself without the alcohol.”

It’s here that the lines begin to blur between Joaquin Phoenix, the actor, and Johnny Cash, the singer (and now movie character). Cash was no stranger to alcohol abuse, even though, as Phoenix points out, “pills were more his thing”. The singer toured constantly from the mid-50s until the end of the 60s, and a cocktail of Benzedrine, Dexedrine and Dexamyl were as central to his brutal touring schedule as his guitar and black suit. Success came almost immediately after he released his first single Cry! Cry! Cry! to some acclaim in 1955. He was in constant demand once his third single I Walk the Line came out the following year, staying in the country charts for ten months.

“I’ve never seen anything like their touring schedule. It was like, play, pack, travel, play, pack... They didn’t have roadies or anything like that. The man was hustling. Non-stop. I’ve never had that kind of experience, but still, in this business it’s hard to have consistency in your life. There’s a lot of travelling and press tours – somewhere different everyday.”

Cash lived a reckless, dangerous and drug-fuelled life on the road. So much so that, by the mid-60s, he was so gaunt it looked to many as if he was heading for a similarly early grave as his contemporary Hank Williams. It was only when Cash married June Carter in 1968 that the singer finally confronted his demons and kicked the drugs and the booze for good. Even then, he still “slipped” a few times, says Phoenix. “Slipped. Now there’s a term I picked up recently,” he jokes wryly, before explaining how he found inspiration in Cash’s attitude.

“I always thought that sober people were pussies – you were a pussy if you couldn’t handle your drink. Then I realised that being sober is one of the most courageous and difficult things to do because it’s life on life’s terms and you don’t get an easy fix. A lot of the film is about Cash getting sober, so it certainly made me think about sobriety and that maybe it isn’t for pussies.”

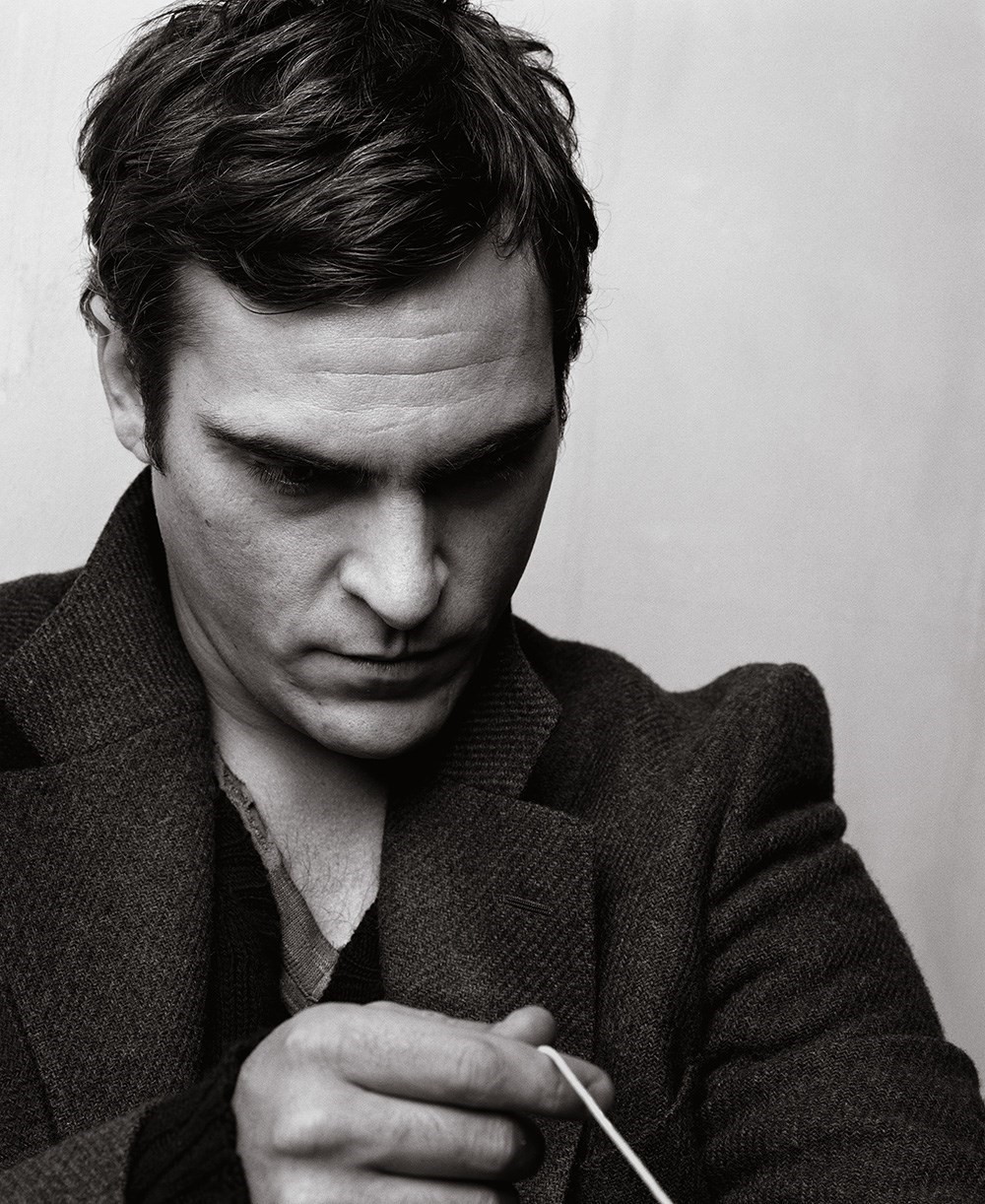

There are other parallels between the life of Johnny Cash and the life (so far) of Joaquin Phoenix – parallels surely not lost on Phoenix as he immersed himself deeper in his subject’s life – reading books, watching film footage and listening to every Cash recording he could lay his hands on. But Phoenix never does things by halves. He makes every effort to “become” the characters he plays, no matter how much that may affect his personal life, no matter how difficult that can be. “It’s not a method,” he says dryly. “It’s an act of desperation.”

Like Phoenix, Cash was raised in a large, tight-knit family that celebrated music and religion. In Cash’s case his childhood was spent in rural Arkansas in the 30s and 40s, where his family had survived the Depression by farming a small plot of land as part of a communal holding. The unusual story of the Phoenix family is already well documented, with the acting success of first River and then younger brother Rain. Suffice to say that John and Heart Phoenix – parents of River, Rain, Joaquin, Summer and Liberty – were simple-living missionaries who travelled with the Children of God around Central and South America during the 70s before settling in Los Angeles in the 80s. They encouraged their kids to be creative, so acting, singing and dancing were common currency in the Phoenix household. By the time Joaquin did his first acting stint on TV at the age of ten, his older brothers Rain and River were already beginning to carve out their careers. It’s interesting that both Cash and Phoenix have taken issue with the assumptions that their early lives were impoverished or unhappy. For both of them, the love of their families overshadowed any hardship.

The final parallel between the lives of Cash and Phoenix is perhaps the most pertinent. A life-changing event in Johnny Cash’s childhood was the death of his older brother, Jack, when he was 12 and Jack was 14. One Saturday afternoon in May 1944 Jack fell on to a circular saw while cutting oak logs into fenceposts. He suffered such severe abdominal injuries that he died a week later. The brothers were especially close and by all accounts the trauma of losing both an older brother and a best friend haunted Cash for the rest of his life.

The relevance of this tragedy won’t be lost on anyone who heard the emergency services recording of Joaquin Phoenix pleading for help as his brother River lay dying on the pavement outside an LA nightclub in October 1993. At the time, Joaquin was 19 and had put his days as a child actor in films such as Parenthood behind him. He hadn’t worked for three years and he withdrew further after his brother’s death. It was not until 1995, when Gus Van Sant offered him the role of Nicole Kidman’s teen lover Jimmy in To Die For, that he slowly started to work again. It was then that he left behind his childhood name, Leaf, which he had been using professionally.

It is impossible to measure to what extent the symmetry of Cash and Phoenix’s young lives affected Phoenix’s performance in Walk the Line.

“At the beginning of a film I try to distance myself from my experiences and the things that make me feel comfortable – things that remind me of myself. It’s always great to go to a foreign city, to a place you don’t know, where you don’t have any friends, and not have to talk to people who you know, and go there with only two t-shirts and a pair of pants and acquire everything else from wardrobe and that’s it.”

Which begs the question: how did he survive filming Gladiator for several months on Malta with only a couple of t-shirts, a pair of pants and the scant wardrobe of a Roman emperor?

All this explains why Phoenix works so infrequently: each film is a massive undertaking – personally, psychologically, geographically. He takes the business very seriously and is as adamant as ever not to be sucked down the path of compromise.

“I’ve just started to look at new things again, but there’s nothing of interest so far. The state of movies and what’s going into production at the moment is painful. It’s horrifying. Goddamn, people have bad taste. There’s no poetic way of saying it: these movies suck. Bad movies are being produced at an alarming rate. No one has any fucking balls. It’s wild.”

In the ten years since To Die For, he’s made 16 films. It’s quite a modest figure. He says he finds it impossible to consider more than one film at a time, and can’t read a script if he’s preparing for or shooting a movie.

“When I decided to do Walk the Line, I called my agent and said I knew I couldn’t work for at least six months afterwards. I wasn’t going to be able to pop out of this character and just drop into something else. One of the movies would suffer, and I’m not going to do that.”

What comes across most vividly from Phoenix’s list of movies is their diversity: two films by creep-master M Night Shyamalan (Signs and The Village); a Ridley Scott epic (Gladiator); an ambitious but flawed sci-fi by Festen director Thomas Vinterberg (It’s All About Love); a post-9/11 celebration of firefighters (Ladder 49, co-starring John Travolta); and a wry dig at the US army in 80s Germany (Buffalo Soldiers). The only real link is Phoenix himself. In essence he’s neither an indie darling nor a Hollywood leading man. He straddles both worlds. Not that Phoenix has seen many of his own films: he stopped watching them a while back.

“I want to continue to act,” he explains matter of factly. “If I quit acting, then maybe I could watch the movies I’m in. But I don’t want to see myself the way other people do. I don’t want to be aware of myself when I work. I’ve seen too many actors who know they look better from this side or that side. I’ve seen it in myself, when I used to watch things. I remember going to work and thinking, ‘Oh God, I’m making that face.’ It’s not just a negative thing either. I might think, ‘Oh, that was a good face that conveyed anger, I’ll use that again.’ For me, acting is about feeling emotions, not just showing them.”

A year before Cash died in September 2003 (and six months before the actor heard that a biopic was brewing), Phoenix received an invitation to have dinner at the country singer’s Nashville home. He remembers how everybody joined Cash in prayer before the meal, and afterwards how he played guitar without fault despite seeming “quite shaky” earlier in the evening. (Cash was quite ill by this time, suffering from diabetes and related illnesses.) Phoenix’s most bizarre memory of the evening is of Cash’s fascination with his character from Gladiator. The ageing singer took great pleasure in reciting, word for word, large chunks of lines spoken by Phoenix’s sadistic, conspiratorial Roman emperor, Commodus. One minute, Cash was praying to God, the next, he was mimicking a manic tyrant.

“He relished every word and gave a better performance than I could have done,” Phoenix remembers. “That was John. Those two things equally – that darkness and that light. A complete person, not denying one side or the other.”

It was six months after that dinner – which turned out to be Phoenix’s first and only encounter with Cash – that the chance arose to play Cash in Walk the Line. The singer was still alive at that point and had been working closely with Mangold on the story, script and casting. Phoenix had Cash’s approval. It means everything to him.

“It was great to know that Johnny had signed off on the script; that his family was involved throughout production; and that Jim (Mangold) had spent so much time with him. Johnny was brutally honest and that’s what comes across in his music. He didn’t pull any punches. He wasn’t ashamed of himself. He just said, ‘This is the way I am, I’m not perfect, I’m trying to do my best, for better or worse.’ It was important to capture that.”

With that, Phoenix finishes his lemonade and wanders off to the bathroom. “Is that Joaq?” asks a young guy sitting near us in the hotel garden. It’s Mike Pitt, the actor who plays Blake, the Kurt Cobain character in Van Sant’s Last Days. When Phoenix returns to the garden, he spies Pitt and gives him a hug. “We were just talking about you,” he says. It’s a neat ending: Kurt Cobain and Johnny Cash both back from the grave and chatting together in the late afternoon sun.

Grooming Catherine Furniss. Photographic assistants Andrew Elliot, Sebastian Lucrecio and Huan Nguyen. Styling Assistant Alex Slavycz. Printing Pascal Dangin for Box Ltd.