Ever since Kim Jones took charge of Louis Vuitton’s menswear five years ago, his ability to interweave the luxury heritage of the storied French house with his own aesthetic devotions has never been less than exceptional. His first collection, S/S12, took the print of one of the Masai blankets that decorates his home and transformed it into plaid cashmere; his A/W15 collection was a rope-printed homage to his beloved hero, design icon Christopher Nemeth. It would be easy for inclusion of these elements to feel appropriative or hackneyed – after all, Louis Vuitton is a behemoth brand that could easily be seen to be riding on the coattails of exoticism and cult iconography. But Jones’ legitimate love for and understanding of these cultures – he grew up in Africa, and is the owner of one of the world’s most comprehensive punk fashion archives – is painstakingly apparent within every component of these collections.

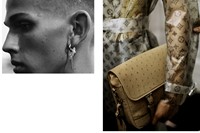

This season was, in some regards, a medley of greatest hits: it was Seditionaries by way of contemporary Africa, with a Chapman brothers collaboration thrown in for good measure (the first Vuitton/Chapman pairing was seen in A/W13, when the brothers’ nightmarish illustrations appeared on silken shirts and brocade jackets). But rather than such a retrospective resulting in nostalgia, it seemed that Jones was elevating and contextualizing previous inspirations anew. Masai checks became exquisitely intricate multi-textural knitwear with a hint of Richard Torry about them (“there’s not many machines in the world that can do that” Jones remarked proudly), safari jackets were printed with lettering evocative of Christopher Nemeth’s post sack collection, Westwood-inspired bondage dog collars were created in Ostrich leather and Louis Vuitton monograms, their design taken from actual Vuitton collars for dogs. The sources of inspiration may have felt familiar, but their realisations were fresh, and completely compelling.

Punk Fetishwear

It’s easy to transform Louis Vuitton into fetishwear – there’s something about applying a luxury monogram to a wallet or handbag and suddenly, as Vuitton creative consultant and stylist Alister Mackie noted, “you gotta have it.” (“I did say that, actually,” laughs Jones, “the minute I saw that wallet I was like ‘I’m having one of those, get a new one for the show’.”) Within the collection, there were the obvious allusions to that aesthetic: the rubber coats that looked like spun silk, stamped with LV, the bike-lock necklaces with the combination of 1854, the aforementioned dog collars, and barbells hanging from shirt collars, but there was also the emphatic reference to that particular era of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren that Jones obsessively collects, that era that celebrated inflammatory glitter glue slogans and, as Michael Costiff remembers, “brought clothes that were about sex to the street”.

“[Seditionaries] brought clothes that were about sex to the street” – Michael Costiff

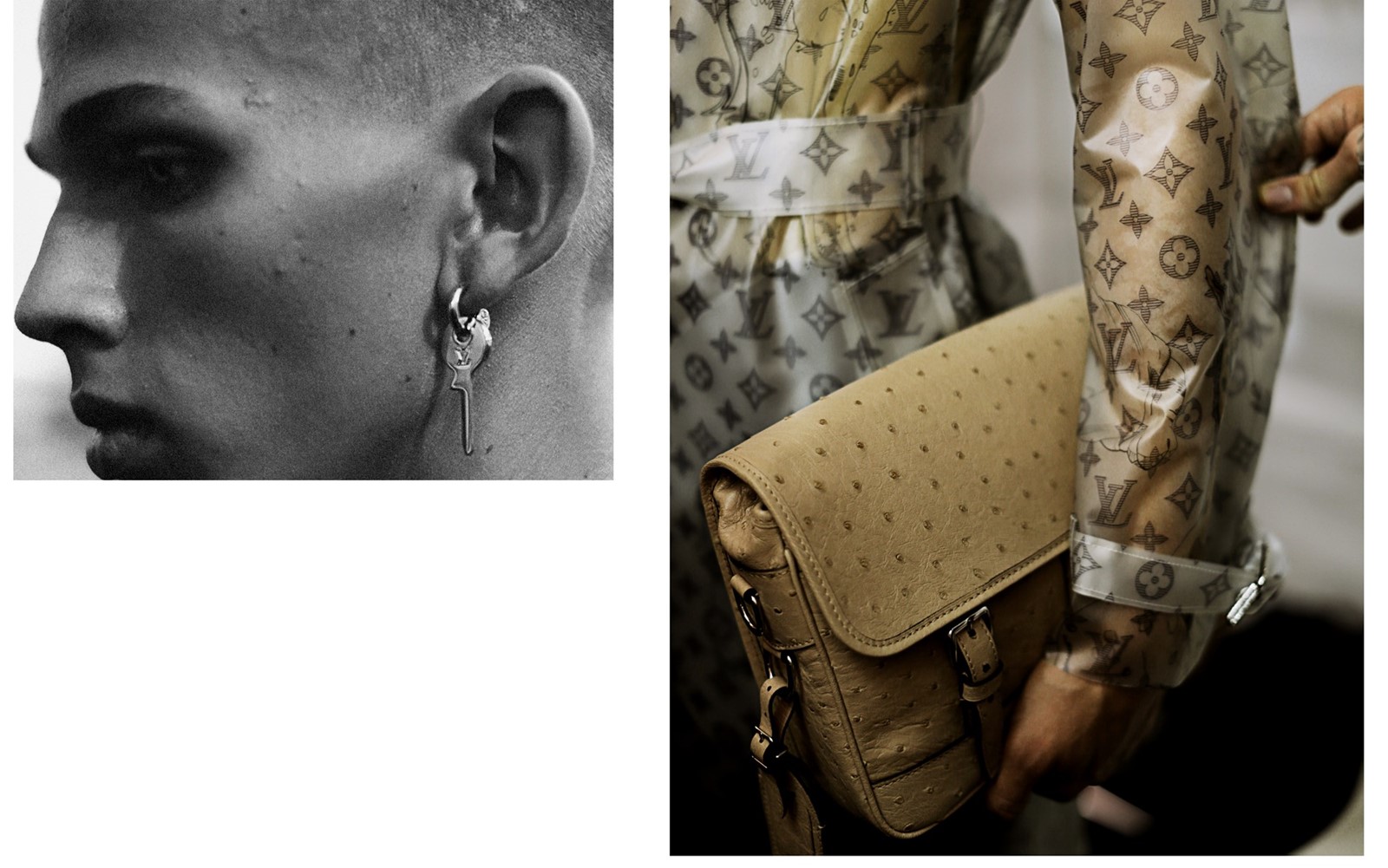

Mohair jumpers – Jones’ archive includes Johnny Rotten’s very own mohair, which he keeps in the fridge for preservation purposes – were in abundance, sometimes printed with the patterns of springboks (the animal-du-jour for this collection, their furs sourced via a South African community who hunt them to keep their land in order). Those Masai checks became tartan trousers dangling with straps, some pairs even featuring zips extending down the back, while ring-pull necklaces and safety pin earrings, moulded in palladium silver, hinted at that DIY mentality. “There was a real inventiveness going on,” said Costiff of Seditionaries. “If you could only afford one item, you could make things out of sink plungers and plugs and chains and mix them all up.” What Jones created was a luxuriant (and somewhat ironic) reworking of this philosophy – as ever with his Vuitton collections, the delight was in the details and covetable, consumable accessories abounded.

The music to which the models walked came courtesy of Mark Moore, and the acid house reverberations of Ten City and S’Express pumped through the Jardin du Palais Royal. While Paul Simonon and Serena Rees and Atsuko Kudo sat in the blazing sunlight, dripping with sweat, it felt like the most apt metaphor for such a collection; what Jones was doing was taking throbbing club culture and teaming it with luxury, celebrating it and bringing it into the light.

Punk Artistry

Aside from under Westwood and McLaren’s ever-evolving enterprise, the same spirit of punk adhoc-ism and guerrilla creativity came together within the collective of the House of Beauty and Culture (HOBAC), a store-cum-creative studio that included the likes of Vuitton beloveds Christopher Nemeth and Judy Blame within its roster, alongside Leigh Bowery and Marc Lebon. Coincidentally, next week the ICA are publishing a book on HOBAC, within which Gregor Muir aptly explains that “the House of Beauty and Culture stands at the hinge of the underlying influence of club culture on UK postmodernism, which would ultimately help ease the way for the YBAs

who were clearly coming from somewhere other than traditional art practice.”

“I like the fact that’s it’s something quite twisted for such a massive house” – Kim Jones

Thus, it makes perfect sense that it was the Chapman brothers – the enfants terribles of the YBA circuit, whose hellish sculptures found themselves at the centre of tabloid controversy during the early 90s – whose work was imprinted upon these garments. They became the latter-day revisioning of the “magical, esoteric sign language” Keith Haring prints writ on Westwood’s Witches collection – but while those collections were created on a shoestring (Nemeth’s post sack collection was indeed made of post office sacks and “Vivienne was struggling for years even when she looked successful,” remembers Marc Lebon in the HOBAC book), this one was rife with the extravagant indulgences of Vuitton – the sorts of sandals you might find at a sporting goods shop were made specifically from ostrich legs, crocodile trenches were handmade and hand-finished.

“I wanted [the Chapmans] to do a kind of big five safari,” explained Jones. “I found these etchings from when people first went to South Africa and started drawing animals, so I gave them those and they came up with the scariest, creepiest version of them.” So, printed on silk and latex and exotic leathers were indeed the scariest, creepiest versions of giraffes and elephants and rhinos and zebras, teeth bared, eyes bulging. Perspex cases that resembled exhibition cabinets were etched with these line drawings in the most literal renditions of fashion-as-art. “I like the fact that’s it's something quite twisted for such a massive house,” he continued – and it was; the ability to turn something quite repulsive into something hideously desirable is a testament to both he and them. The traditional Louis Vuitton clients might first and foremost be those seeking beautiful trunks or impeccable leathers, but Jones broadens the horizon beyond that, offering pieces that are simultaneously rife with meaning, utterly bewitching, and appealing to an entirely new demographic.

Punk Africa

Finally, and pivotally, the contemporary styling of some particular African communities figured as a key component and source of inspiration for this collection – after all, and perhaps above all else, it was clearly Jones’ second homage to Africa. His childhood was spent on that continent – his father was a hydrogeologist, and thus moved around from Kenya to Tanzania, Ecuador to Botswana and Ethiopia – but it was the latter two of these countries that has had a particular influence on S/S17; specifically, the Botswanan biker gangs captured by photographer Frank Marshall, and the people of the Omo Valley who photographer Alex Franco has recently been documenting (for a book that Mackie is helping edit, and for which Jones is writing the foreword). These Omo Valley tribes, Franco explains, “mix western fashion with tribal traditions,” pair Obama T-shirts with strings of beaded necklaces, dozens of colourful hairclips and – as was incorporated into the Vuitton show – wear keys as earrings.

“We liked the image of a guy like Paul Simonon or Joe Strummer, but we also liked these images of Ethiopian guys hanging out together” – Alister Mackie

“These people have a very trend-driven, punk approach to their style,” Franco continues. “Essentially, punk was based on DIY – recycling things, stitching your clothing, painting a new body – and this is precisely what these tribes have been doing: I saw them turn bottle tops into headpieces, wear watches as necklaces, cut up top-up cards to make jewellery.” So in amongst the safari prints, Savannah-bleached palette, and exotic leathers, it was modern Ethiopia and Botswana that informed the African aesthetics of the collection. As Mackie aptly summated, “we liked the image of a guy like Paul Simonon or Joe Strummer, but we also liked these images of Ethiopian guys hanging out together and dressing in this very punk way. That’s where the character came from in that narrative of Africa.”

And perhaps that’s precisely how, in amongst its hyper-luxury fabrications and unparalleled technical precision, Vuitton manages to achieve such convincing authenticity: it is so very character-based, so thoroughly and devotedly researched. It would be terribly easy for a Masai check, or a zipped trouser, or a brothel creeper fashioned from a zebra-printed springbok fur to feel incredibly out of touch, even patronizing, when coming from such a house – but through Jones’ hand, it ends up far from that. Instead, what amounted for S/S17 were pieces that were exceptional in their finesse, will sit appropriately on a Louis Vuitton store hanger, but when combined make for a vision that is brilliantly intricate yet entirely harmonious. This was an appropriate celebration of the past ten seasons – as Jones said, “It’s quite nice to do that, and then move on.” We’ll just have to see where he moves to next.