We expose the story behind the image-maker’s most celebrated nude study, a paragon of Modernist photography

This month marks the release of a trilogy of photo books by Taschen, each dedicated to an American 20th-century photographic “master of light”: Man Ray, Edward Weston and Paul Outerbridge. Here, in a three-part dedicated series, we explore the story behind an enduring image from the second: Nude (Charis, Santa Monica) by Edward Weston.

Edward Weston was a vital pioneer of Modernist photography, who helped elevate the status of his chosen medium to that of a revered art form. He was born in Chicago in 1886 and began taking pictures after receiving a Kodak Box camera from his father for his 16th birthday. He found early commercial success with a pictorialist style of image-making, using a soft-focus lens to create painterly portraits, but by the 1920s had adopted an increasingly experimental approach to his craft. In 1922 he took an arresting series of photographs of the Armco Steelworks in Ohio – widely viewed as his first Modernist feat – capturing its dark towers imposed against a bright white sky. A year later, he ventured to Mexico with his lover Tina Modotti, where he remained for the next five years, developing the radical stylistic traits that would come to define his later practice. This involved using a close-up lens and natural lighting “to make the commonplace unusual”, and saw rocks, clouds and plants rendered remarkably sculptural studies in line and texture.

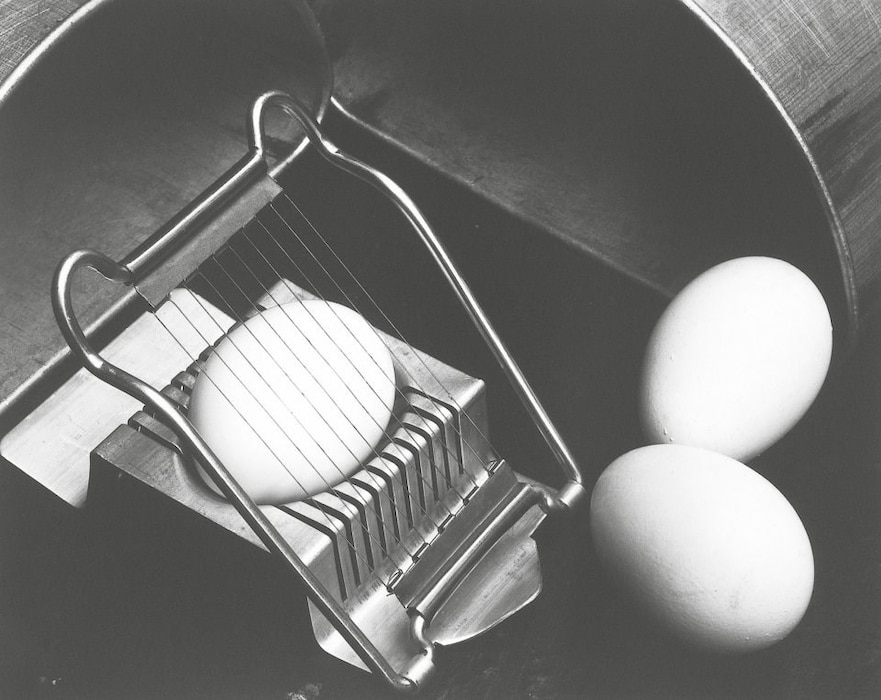

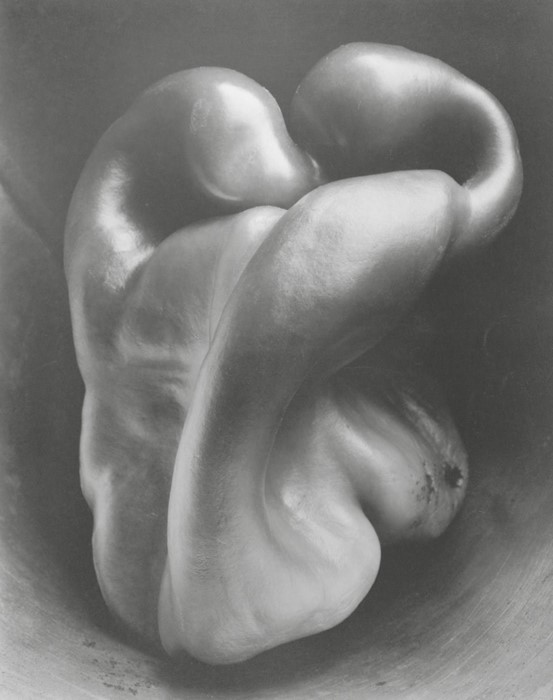

Weston moved to California in 1928 and continued to capture everyday objects up-close, from egg slicers and cups to shapely green peppers, to celebrate and elevate the fundamentals of their form. “The camera should be used for a recording of life,” he wrote in one of many journal entries at the time, “for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.” In 1932, Weston co-founded Group f/64, a collective of west coast photographers championing what came to be known as “straight photography”, whereby “no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other form” should be present. Some of the most mesmerising demonstrations of this photographic approach can be seen in Weston’s various nude studies, breathtakingly unique works within one of art’s most expansive genres.

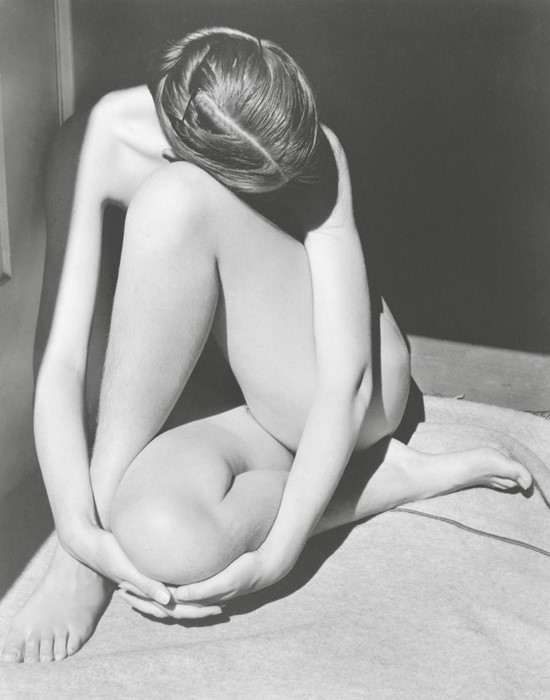

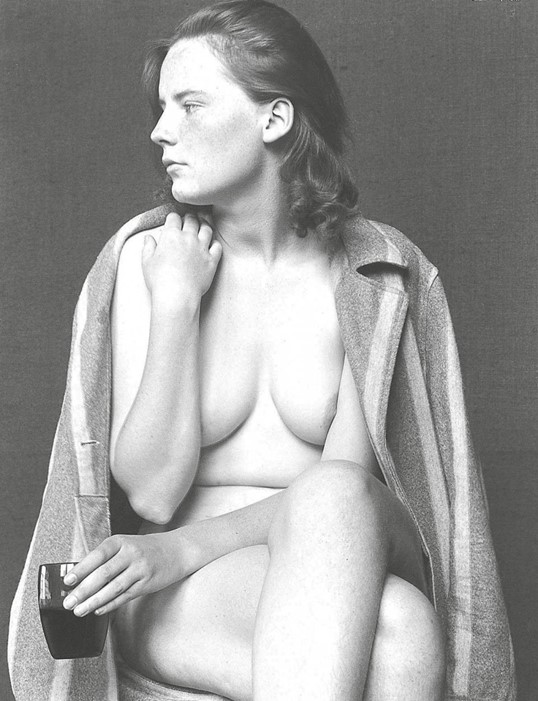

Many of Weston’s most famous nude images depict his muse and assistant Charis Wilson, whom he met at a concert in April 1934 and described as a “tall beautiful girl, with a finely proportioned body, intelligent face well-freckled, blue eyes, golden brown hair to the shoulders”. In 1935, feeling the strain of the Great Depression, Weston, Wilson and his three sons moved into a small house on Mesa Road in Santa Monica. He and Wilson took the master bedroom, which boasted a large sundeck overlooking the ocean. It was here that Weston took what is arguably his most iconic photograph of Wilson, Nude (Charis, Santa Monica) (1936), a year before they were married. Wilson sits on a woollen rug – supposedly because the deck’s silver surface was too hot for her bare skin – one leg crossed majestically over the other, with her arms encircling them. Her head rests on her knee, parted hair directed towards the viewer, her face obscured.

“I sat in the bedroom doorway with the room in a shadow behind me. Even then the light was almost overpoweringly bright. When I ducked my head to avoid looking at it, Edward said ‘Just keep it that way,’” Wilson later recalled of the photograph’s realisation. “He was never happy with the shadow on my right arm, and I was never happy with the crooked hair part and the bobby pins.” In spite of the photographer and his sitter’s reservations, the image has since been declared a Modernist paragon for its extraordinary investigation of the human body. As The New York Times critic Hilton Kramer notes, “To Weston’s eye… the landscape of the human body was an unending revelation of forms both voluptuous and abstract. His genius as an artist lay in his ability to respond to both with equal passion.” This was, historian Nancy Newhall observes, something the photographer achieved by using light “like a chisel”, noting how “the luminous flesh rounds out of the shadow, and the shadow itself… is as active and potent as the light”. And indeed, in this sumptuous and lyrical work, Weston undoubtedly succeeded in making art that could never be executed in any other medium.

Edward Weston, edited by Manfred Heiting, is available now, published by Taschen.