Weronika Gesicka’s uncanny scenes, on display now at Foam, take what we think to be ‘ordinary’ and turn it upside-down

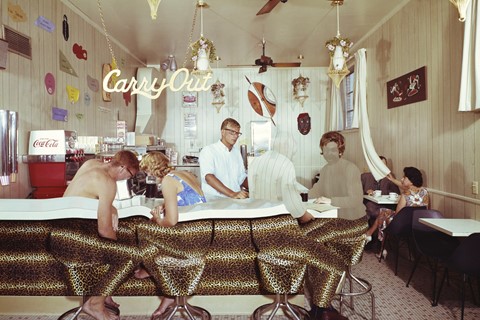

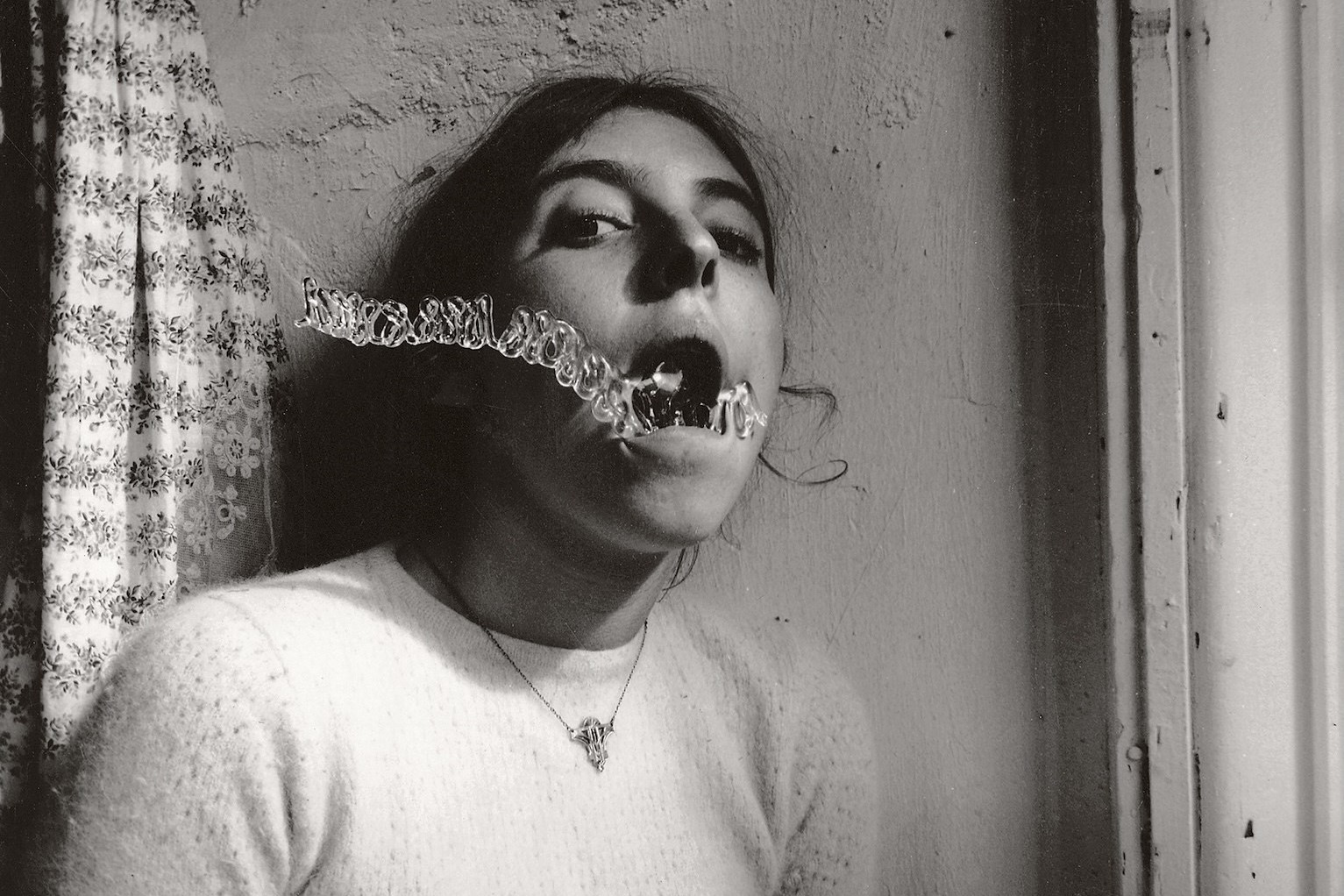

When our eyes look at an image or a scene, how much of it do we really see and how much does our mind fill in on its own? Questions like this lie at the heart of Weronika Gesicka’s work, in which familiar images are rendered uncanny and reality becomes slippery and unreliable. Amidst the milieu of beaches and suburban homes in the American midcentury family album, masks cover heads without faces and bodies break into pieces, dissolving into the background. In her series Traces, the Polish photographer takes found photographs from 1950s and 1960s archives, then manipulates them until they appear off and uncomfortable, inviting the viewer to take a closer look. In doing so, we start to question whether or not we can trust our own perceptions.

“I love archives,” confirms Gesicka, whose work is currently on view as part of Amsterdam’s Foam Talent showcase of emerging photographers. “During one of my searches I came across photographs which at first glance looked as if they were taken from a photo family album. For me, what was really interesting was that it wasn’t completely clear if they were from a real family album, or if these photos were completely staged and the people were only actors or models pretending to be families.” During her searches of library collections, photobanks and even vintage crime archives, Gesicka started to notice the same faces popping up in different homes, different situations, and began to wonder about these people and their lives. “It was interesting, but also a little bit creepy because it’s very strange to see the same people but, for example, posing in a totally different house.”

Gesicka modifies the found images until they become something entirely new. But what remains is an almost Lynchian miasma of uncertainty and the uncanny, as well as the preoccupation with the idea of an idealised life as expressed in the image. That preoccupation is something that we’re still just as obsessed by today, I propose, in the form of social media and the quest for superficial perfection and validation. “It’s a quite similar situation,” Gesicka agrees. “For example, on Instagram we only put these photographs which for us are perfect, and this world, from 1950s and 1960s American archives, is also a perfect world with perfect colours. Today we have some filters, but I think the colours, the worlds from American archive pictures are also like Instagram filters: a specific mode, a specific atmosphere, a specific light.”

After studying at Warsaw’s Academy of Fine Arts and later Academy of Photography, Gesicka’s practice has centred on photography, although she also makes objects that sometimes form the basis for her photographic projects. “I try to make my work a little bit funny, a little bit creepy. To make it so you know something is wrong but at first glance you can’t tell what exactly it is.” Often the tension in these images comes from the idea of memory, and the ambiguity around our capacity to trust our own narrative of events. “For me, memory is everything because we are who we are because we have our memories,” she explains. “So we find memory in every day, in every thing. It’s a huge theme, but I think we can see memory from so many perspectives.” Today, Instagram and Facebook have taken over the role of the family album in our lives, with social media platforms happily inviting us to walk down memory lane by parading old images in front of us daily. Photography and memory have become, to some extent, one. But Gesicka’s work suggests that we might be better off questioning what we see and remember, rather than accepting it wholesale. “Sometimes we believe in photography like we believe in our eyes,” she says. “We think it’s the most objective medium, but I try to show that it’s quite the opposite.”

Weronika Gesicka’s work is on display as part of Foam Talent at Foam Museum, Amsterdam, until November 12, 2017.