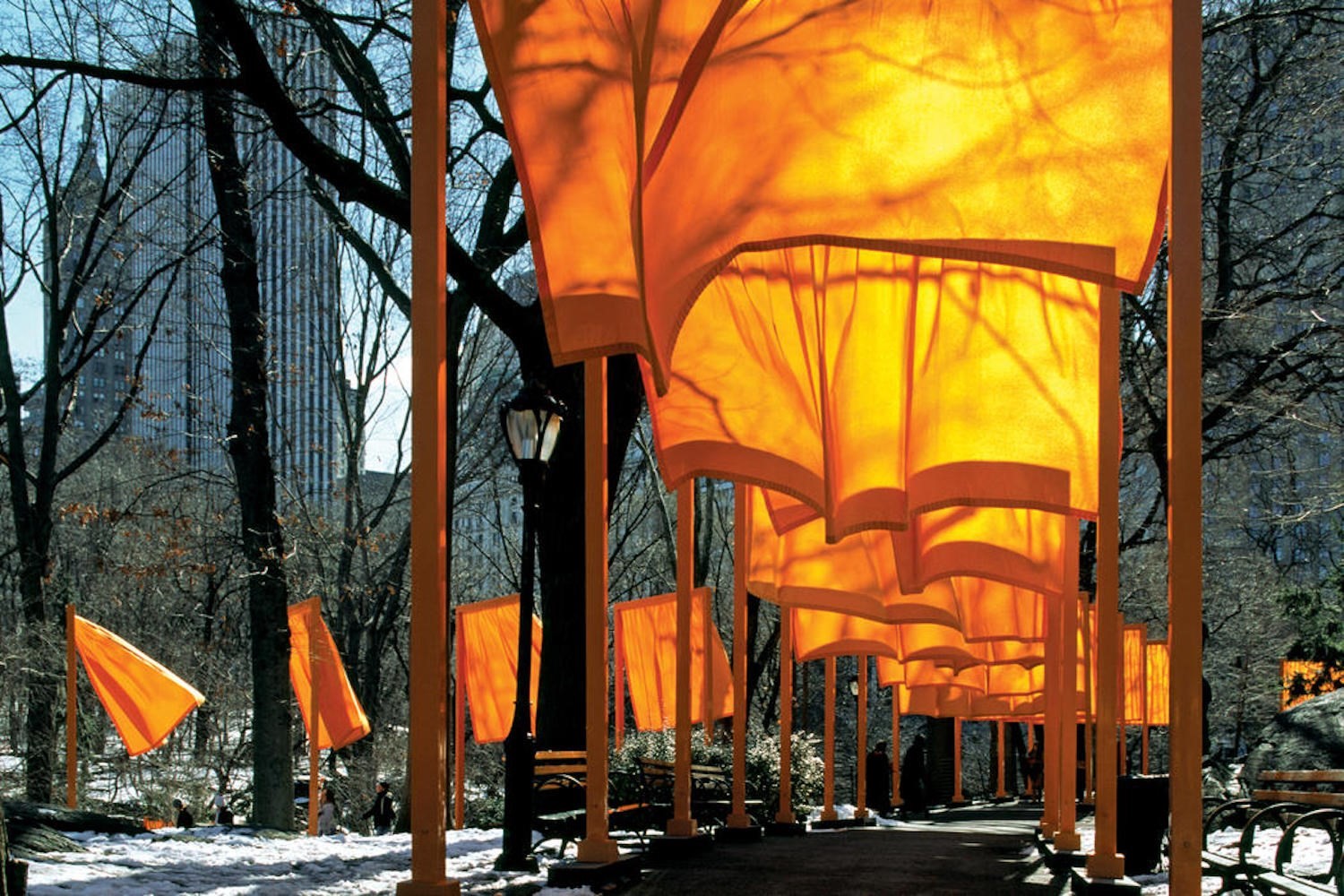

Christo is a man with big ambitions. The artist, along with his late wife Jeanne-Claude, is best known for his projects which see bridges, government buildings and entire islands wrapped in in fabric. He also filled New York’s Central Park with over 7,000 bright orange gates, and installed more than 2,000 giant umbrellas across California and Tokyo. To the public, these magical feats of engineering immediately beg two questions: How? And, why?

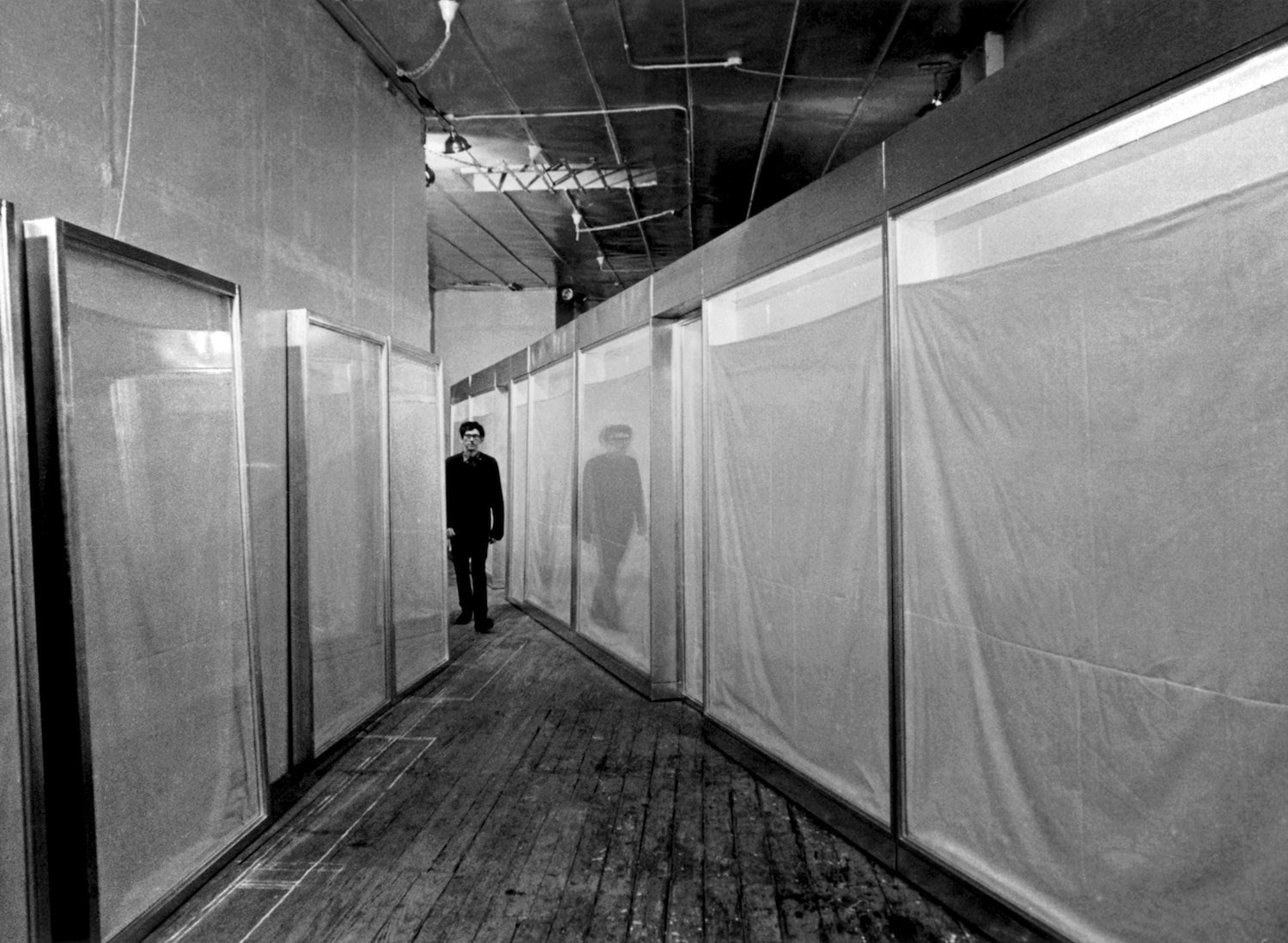

Here, ahead of the reassembly of one his earliest works, Three Store Fronts, at the Belgian art fair BRAFA (where he is also guest of honour) we sit down with the notoriously tight-lipped artist and find a man keen to set the record straight on his practice, and how it is not just about art, but business too.

As if brought together by fate, Christo Vladimiroff Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon were both born on June 13, 1935. A young Christo fled the Communist regime of his native Bulgaria, spending 17 years on the run as political refugee. In 1958, he met his future wife, who hailed from Morocco, while living in Paris. The pair wed, moved to a loft in Manhattan and decided to begin a collaboration. Christo would be the artist, and Jeanne-Claude, the organiser.

The couple’s loft in Manhattan still operates as the nerve centre for his practice. “The top floor is my studio, where I create every single artwork. I have two assistants that I inherited from Jeanne-Claude after she died, her nephew and my nephew,” he says. “But they’re not allowed upstairs. It hasn’t been cleaned since I moved in and I know if I put something down 50 years ago, it will still be there.” The remaining five floors of the home are his living quarters, a storeroom, a hospital specification generator (the building is self-sufficient) and a room where he sells his work. “I never work exclusively with galleries,” he says.

His principal storage, though, is based in Basel, Switzerland, organised under a complex system of umbrella companies. “In the 1960s my lawyers told me to set up holding corporations based in New York and Delaware. We sell all our sketches, collages and models through my holding company CVJ, with the proceeds funding future projects,” he says. “We also use the company to buy back our works, which return to storage and become collateral for bank loans. I am my own biggest collector.”

Christo’s earliest works, including Three Store Fronts, which will be shown at BRAFA, consisted of small shop windows draped in fabric with dimly lit, veiled commercial interiors. “These grew into life-sized storefronts which took up entire galleries,” says Christo, hinting that, in hindsight, these works were the seedlings of his later monumental outdoor wrapping projects.

In 1969, Christo and Jeanne-Claude set their sights beyond the studio, wrapping the coastline of Australia with almost 100,000 square metres of white fabric and employing 100 workers to climb, pin and unfurl it in a process that took close to 20,000 hours. The following decades saw Germany’s Reichstag building, the Pont Neuf bridge in Paris and a series of islands in Lake Iseo, Italy, wrapped too. The latter became the most visited work of art in 2016, despite lasting just 16 days.

“The works have two phases. The first is software,” Christo explains. “This involves drawing, sketching and planning, but also picking spaces. For some works we need to scout locations, which can take decades. Other projects such as the gates in Central Park, New York, have designated homes. In order to do this work, we had to rent the park from New York, which cost us $3 million. For the Reichstag project we had to first convince the public, then there was a debate in the German parliament that everyone said we would lose, but we won.

“Then the second phase is hardware. We begin making mock-ups, ordering supplies and contracting employees. All of this, you see, is part of the art. The meaning of each project is the long journey that ends with the installation. The work can only last ten days, but might have spent 25 years growing.”

When presented with quotes stating that his work contains no deeper meaning than its immediate aesthetic impact, the artist is quick to rebuke. “That’s not true. People are idiots. Each project is completely irrational. I don’t do commissions and everything only exists because Jeanne-Claude and I want it to,” he says.

“People are idiots. Each project is completely irrational. I don’t do commissions and everything only exists because Jeanne-Claude and I want it to” – Christo

“Everyone is also entitled to their own interpretation,” he continues, pondering the ways different works are received in different countries. For example: “The umbrella project was a diptych where we installed huge umbrellas in the countryside outside Tokyo and in California. In America people drove around the yellow umbrellas, but in Japan people removed their shoes, as if they were going in to their homes, and picnicked beneath the blue umbrellas.”

When asked about how the colours of the umbrellas were selected, Christo reveals a simple truth: “We wanted the work to take place in the summer. In California the grass by then is burnt yellow in the sun, while in Japan their summers are wet and the rivers swell with blue water. The colour of the work is the last element we decide, and is picked by how we view the environment.”

With project costs always running in to the millions of dollars, finance remains a key consideration. “For the gates in Central Park we ordered 5,000 tonnes of steel – that’s two thirds of the Eiffel Tower. But before we even placed the order, I had resold the steel to the Chinese construction industry,” he says. “People also assume the fabric is expensive, but we use petrochemical compound materials that are a by-product from the oil industry.”

“In 2006, Harvard Business School called to tell me they wrote a three-page case study on how I fund my work. The only other case studies were on Steve Jobs and Bill Gates” – Christo

The biggest cost comes in the form of labour. The staff for the gates project in New York cost $600,000 a day. Surrounding 11 islands off the Florida coastline with 6 million square feet of pink fabric is rumoured to have cost even more. “In 2006, Harvard Business School called to tell me they wrote a three-page case study on how I fund my work. The only other case studies were on Steve Jobs and Bill Gates,” he laughs.

Last year, Christo announced that he was pulling the plug on a project that would cover 42 miles of the Arkansas River in silver fabric, after 20 years of planning. The artist stated that he had no interest of finishing the project while Donald Trump remained the president of the United States.

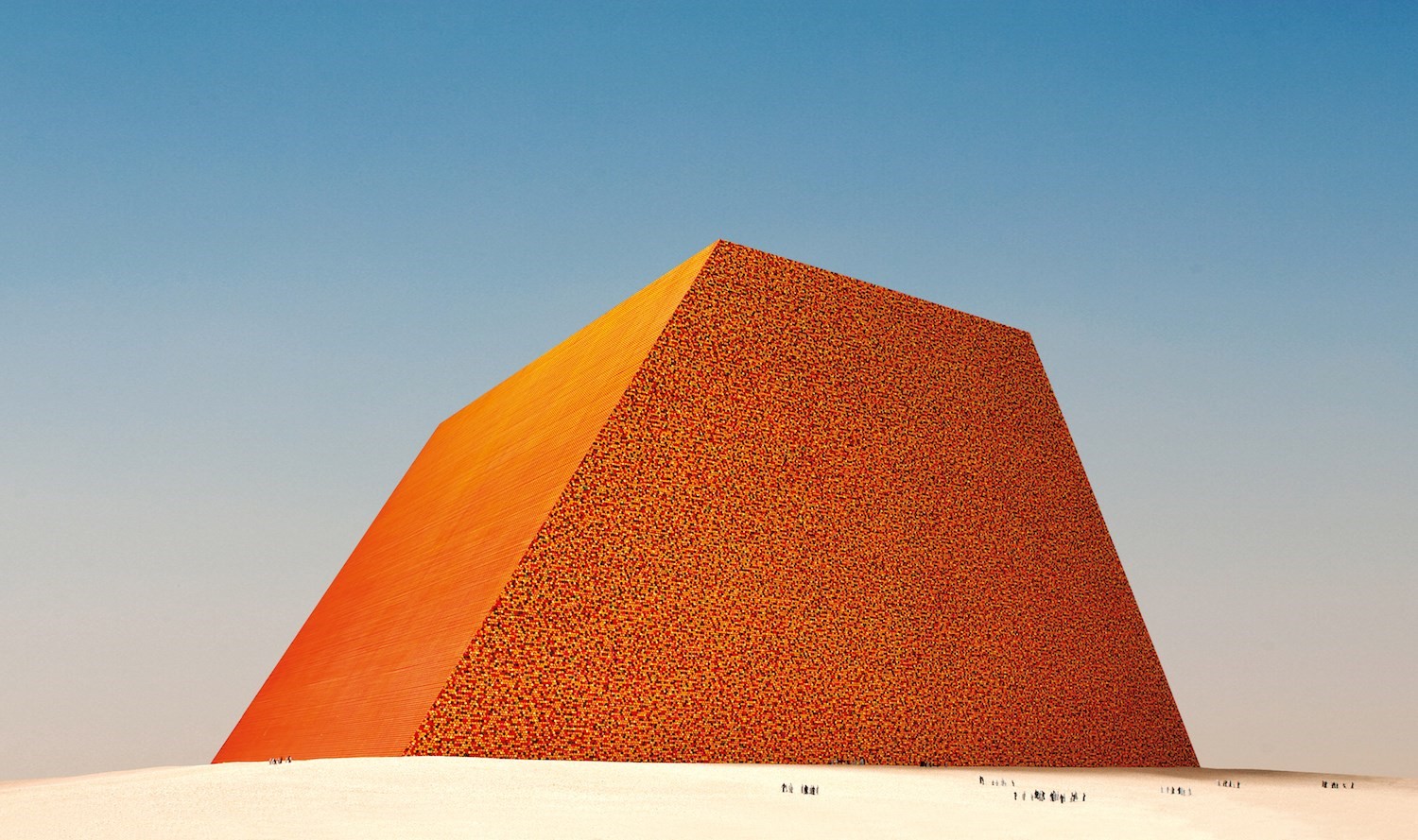

That said, Christo’s most ambitious project is still to come; having worked with oil barrels since the 1950s, the artist has been planning to build the world’s biggest sculpture in the Abu Dhabi desert, a project no less than 40 years in planning. Consisting of 410,000 barrels stacked in a trapezoid over 150 metres tall, the work will be the first of the artist’s to remain in situ and is named Mastaba after the front benches outside homes in ancient Mesopotamia – the first of the world’s urban civilisations found in modern day Iraq.

“We initially wanted to build it in Texas, then Holland, but both times we were refused,” says Christo. “Then a collector, who happened to be the French Foreign Secretary, flew us to Abu Dhabi in 1972. We saw a site and decided to do it there.” A version of the work is set to be floated on London’s Serpentine lake after Westminster Council agreed in January 2018, and will form part of an exhibition at the nearby Serpentine Gallery.

As for the work being shown in Belgium, Christo clearly has one thing on his mind. “It’s a hugely important piece that illustrates the beginning of my career. A museum should buy it, and the money will finance Mastaba.” The asking price? “$16 million. And that’s not a secret.”

Three Store Fronts (1965-66) will show at BRAFA, Brussels Art Fair, January 27 – February 4, 2018.