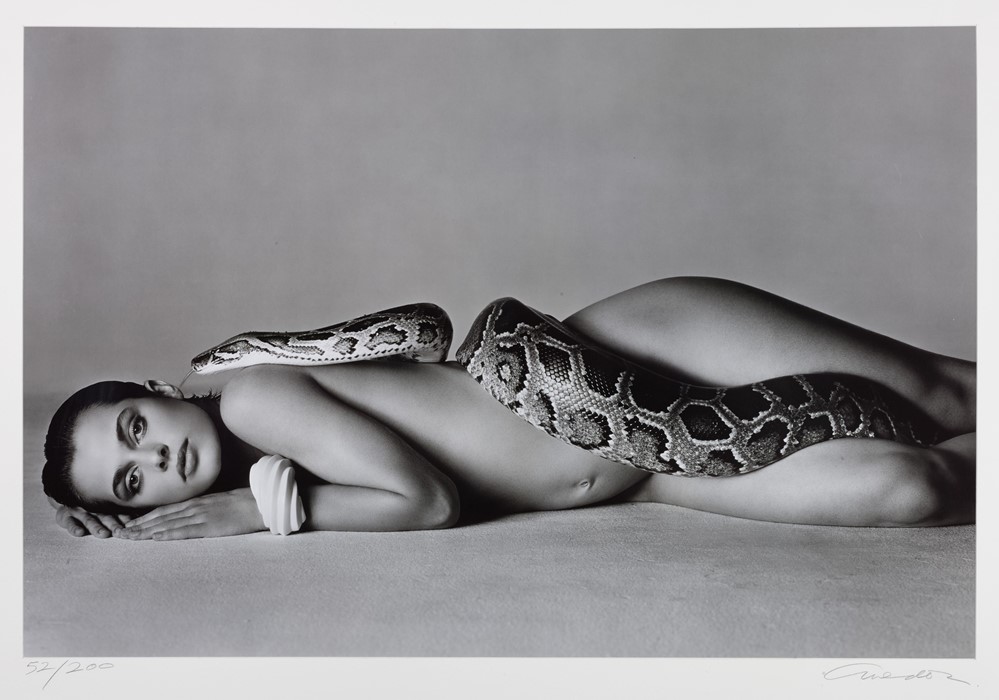

As the oft-referenced image goes on sale as part of Sotheby’s erotic art auction, we look at how Nastassja and the Serpent was realised

According to American Vogue stylist Polly Mellen, the arrival of a snake on set was an unexpected turn of events. “We were in Los Angeles, and the shoot had already started. We were just doing fashion pictures,” she recalls in the 2001 documentary In Vogue: The Editor’s Eye. Looking for something to give the images a little extra kick, she asked model Nastassja Kinski if she had any ideas. Kinski’s reply? A boa constrictor. Naturally.

In 1981 Kinski was at the height of her career, modelling for the world’s leading fashion titles and appearing on screen for cutting-edge auteurs from Polanski to Wim Wenders. The legendary Richard Avedon had been charged by editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland with capturing the woman of the moment: following his blockbuster 1977 show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the largest photographic retrospective the institution had ever staged, Avedon was arguably America’s most famous lensman.

The creative alchemy between these two industry titans would produce one of the most referenced fashion images ever, most recently recreated by Patrick Demarchelier and Jennifer Lawrence for Vanity Fair. Swiftly put into production by Condé Nast as a poster, Nastassja and the Serpent became ubiquitous as the décor feature of choice for any testosterone-fuelled 80s college dorm. Currently on display at Sotheby’s as part of their Erotic: Passion & Desire sale and going under the hammer next week, seeing an edition of the image in the flesh tells a different story of its creation and legacy.

“What I find interesting is that you have this incredibly famous male photographer, so you assume that he’s in control and calling the shots,” explains Sotheby’s Head of Photographs, Brandei Estes. “But then here’s this 21-year-old sex symbol saying, let’s do it with a snake and in the nude. Kinski was completely calm and in control and professional, even as she lay on cold concrete for hours with the snake hooked around her feet.”

It’s worth noting also that the title, Nastassja and the Serpent, carries a distinct echo of an Old Master mythological painting – quietly playing with the tradition, famously observed by John Berger his 1971 essay Ways of Seeing, of the history of art as ‘men [looking] at women’ while ‘women watch themselves being looked at’. Even if the subtleties of this were likely lost on its largely male, heterosexual fanbase, in Avedon and Kinski’s subversive take on this image type, the female subject is in control – not just behind the scenes, but visibly in the end product.

The phallic trunk of the snake gives the painting an erotic flavour, but carefully steers clear of anything pornographic. Kinski’s body is rendered smooth as sculpture, her gaze direct and stoic, unfazed by the slithering strength of the beast on top of her. “Avedon’s not known for taking erotic photographs, so for him this was probably a step outside of his comfort zone,” Estes adds. “You don’t actually see anything explicit, but I like that ambiguity.”

There’s also the easily missed detail that is the cherry on the cake when seen in person. After two hours of trying to coax the snake to move all the way up Kinski’s body, the crew were growing impatient. All of a sudden, it began to glide its way across her curves and up to her head. As Avedon whispered to Kinski, “this is it!” the snake bared its fangs before flicking out its tongue, as if leaning in to kiss its 20th-century Eve. “It was magical, completely magical,” says Mellen. “When the snake kissed her and the tongue went into her ear, that was it. The shoot was over.”

Erotic: Passion & Desire is on display at Sotheby’s until February 15, 2017, when the auction will take place.