Being the only child of one of Italy’s most important contemporary artists comes with its fair share of responsibilities. “One day my father came to me and said, ‘You’re going to have a big storage problem,’” says Beatrice Merz, the daughter of Mario Merz. Her father’s proposed solution? “He wanted to take all of his works into the street and have a big sale,” she laughs. Thankfully, Beatrice quickly dissuaded Merz from his plan; instead they began to collaborate on Fondazione Merz, a contemporary art centre located in a former industrial district of Turin.

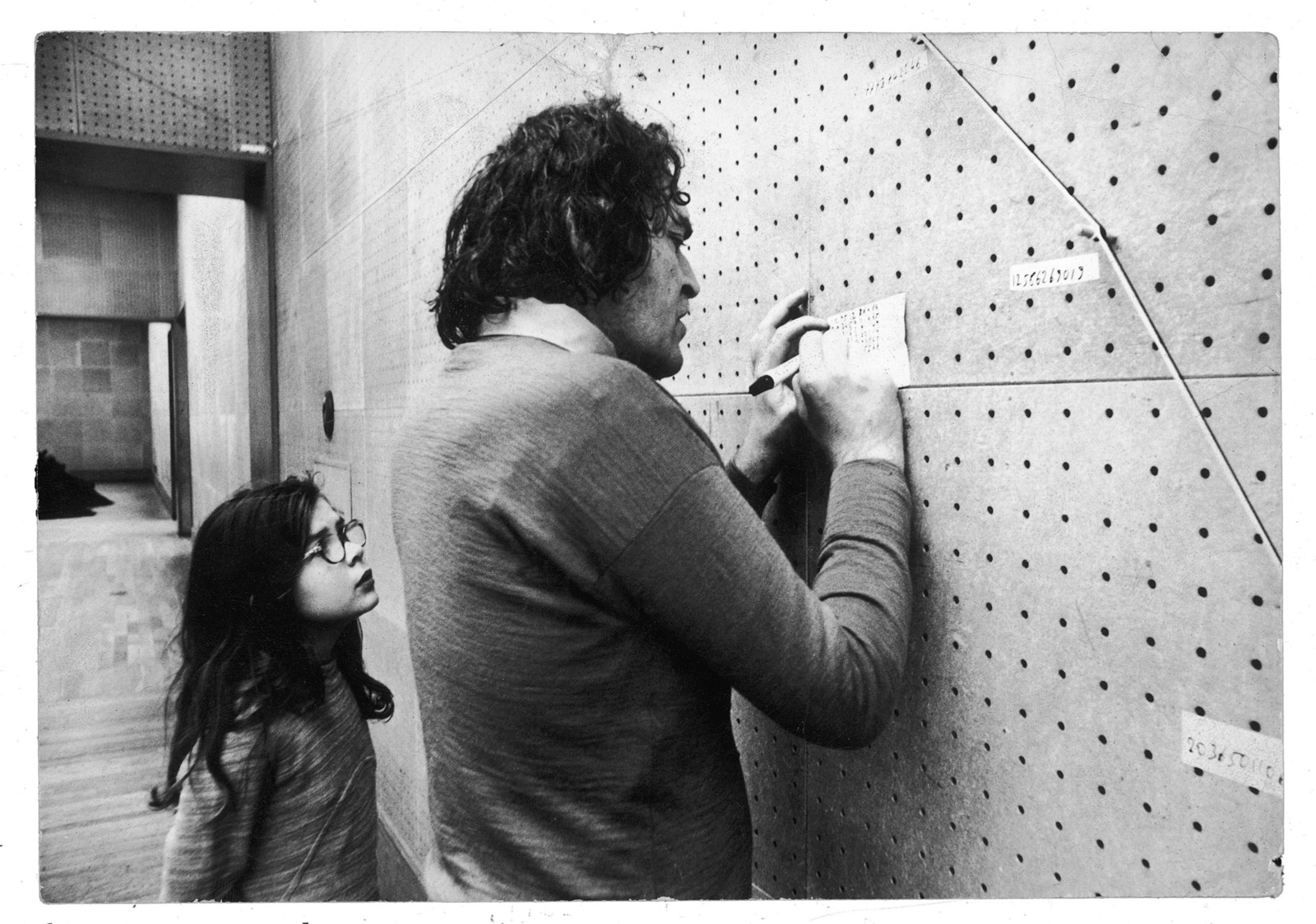

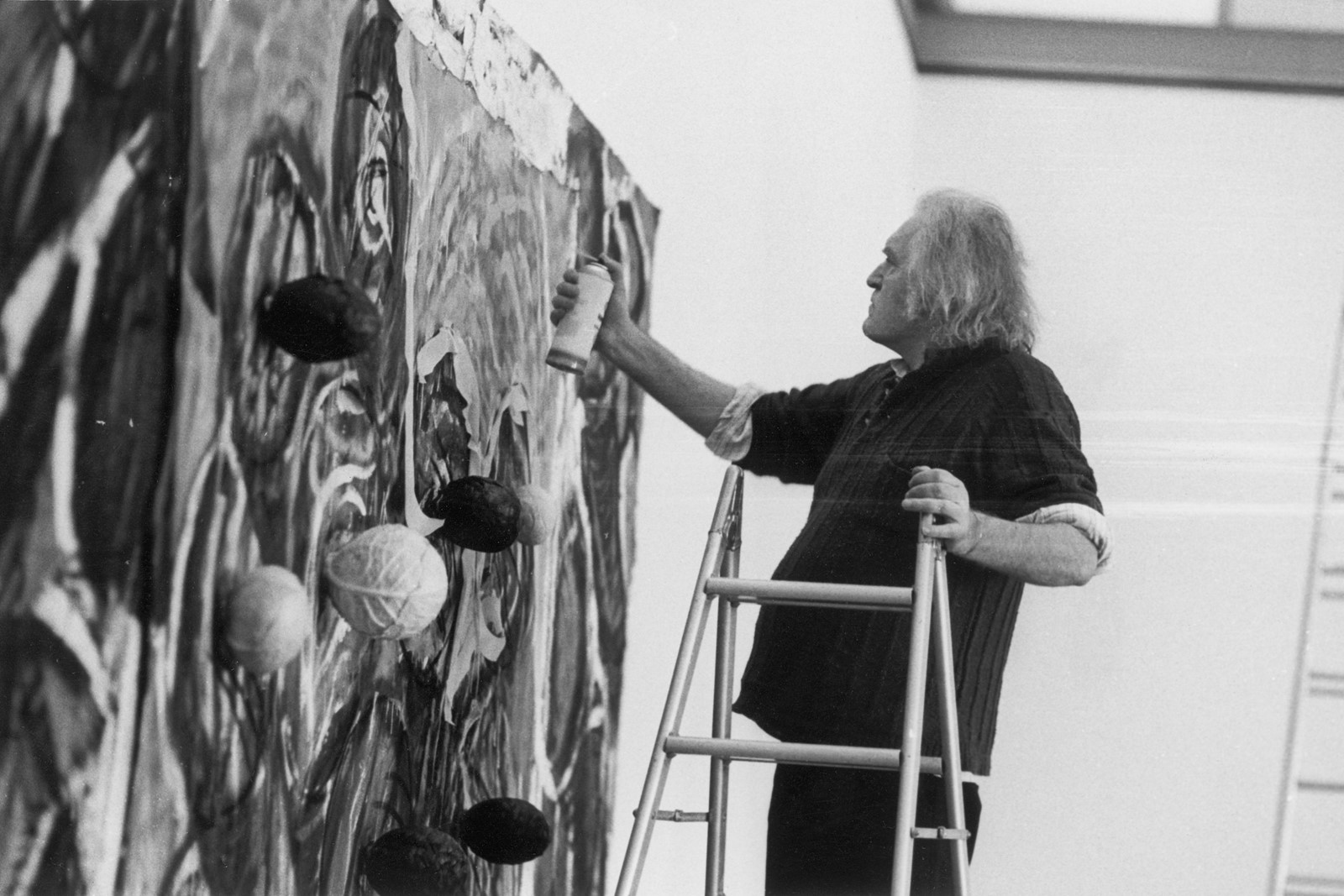

The late artist’s laissez-faire attitude to what became of his estate is less surprising when considering the art in question. Along with his wife, Marisa, Merz was one of the key figures of the Italian avant-garde art movement known as arte povera (poor art), whose members rejected using bronze, gold and marble in favour of common materials, such as soil, glass and twigs. In doing so they stood against what they perceived as elitism in the art world in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In keeping with the openness of Merz’s approach, it was clear to Beatrice from the very beginning that the foundation shouldn’t be a static tribute to her father. Instead, Fondazione Merz is a dynamic space featuring solo presentations by a diverse group of artists (Simon Starling, Klara Walker and Alfredo Jaar to name but a few) alongside thematic exhibitions centred on Merz. “When we began the foundation [in 2005] it wasn’t to create a monumental space or a monumental artist, it was to continue Mario’s relation with the world of art and the world in general,” she says. Their current exhibition comes 50 years after the protest movements of 1968 and features 12 works by Merz inspired by this worldwide period of anti-government demonstrations and uprisings.

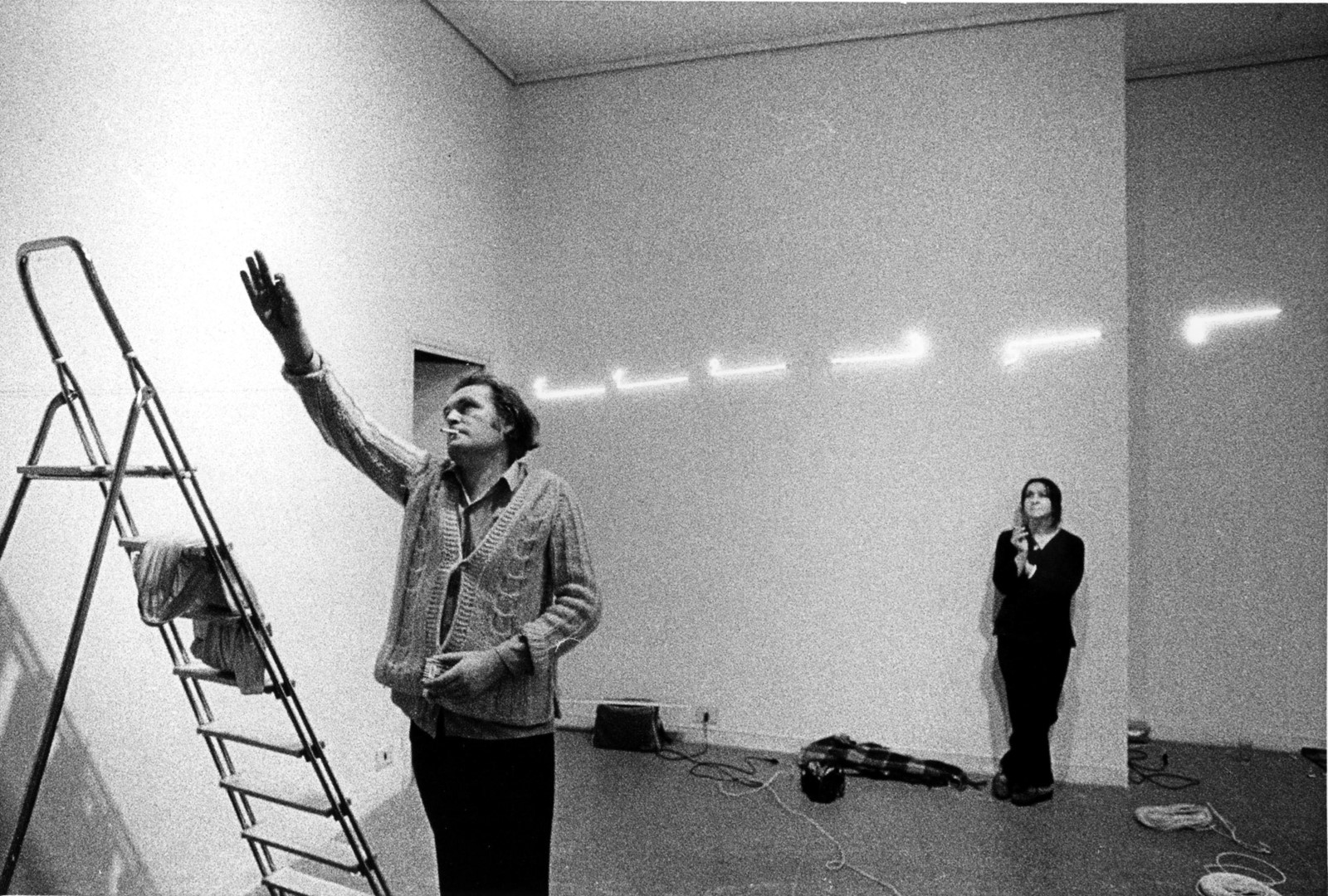

At the centre of the main exhibition space is the titular work Sitin (1968), which Merz created after seeing the words “solitary supportive” scrawled on a wall during the most intense period of occupations and general strikes in France. Fascinated by the juxtaposition of seemingly opposing adjectives, Merz set about recreating the graffiti’s essence in sculptural form. The result is characteristically unassuming: a rectangular frame covered in a wire mesh is placed directly onto the floor and combined with the words ‘sit in’ made from blue neon. Look closer, though, and it’s clear that the surface of the work is covered with a layer of wax that partly sits on top of the mesh and is partly absorbed into it; the materials are both separate from and supported by each other in a physical evocation of the anonymously authored slogan.

For Merz politics has always been inseparable from art; during World War II he was imprisoned in Turin for handing out anti-fascist flyers and it is there he began to draw. His invitation to stage a sit-in, a form of nonviolent protest with roots in the civil rights movement, is particularly fitting considering that Fondazione Merz is located in a former car factory. Indeed, many of the works in the exhibition thematize the concept of worker solidarity and the importance of leisure time. A real sum is a sum of people (1972) comprises ten photographs documenting a performance in a pub in London’s Kentish Town. Another work, It is possible to have a space with tables for 88 people as it is possible to have a space with tables for no one (1973), is a group of different sized tables intended for sharing. In each case the number of people either physically in the room or suggested to be so is written in neon and corresponds to the Fibonacci sequence. Invented by a mathematician in the Middle Ages, in this sequence each number (after the first two) is the sum of the previous two and can be translated into an expanding spiral that is widely present in nature. Unlike many other geometric forms, the spiral suggests continuous expansion – a concept that greatly inspired Merz and fellow artists with an interest in the natural world. Richard Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), for instance, is arguably the most recognisable pieces of land art ever made and is a perfect example of the Fibonacci sequence at work.

It is often said that nature doesn’t recognise borders and Merz would no doubt agree; like many of his contemporaries he saw himself a citizen of the world. With this attitude came a profound respect for democracy. “The one thing I learnt [from my father] is working together with mutual respect,” explains Beatrice. “He was an artist, he didn’t care about practical things, but he was very strict about that.” It is this kind of collective thinking that allowed for the events of ’68 to unfold across Europe and eventually the world. In times of political upheaval the tendency is often to question the relevance of art and culture altogether – but perhaps a practice like Merz’s can show us a more productive way forward. Though his own unique perspectives on the world, he developed a social practice that, instead of placing the artist on a pedestal, dropped him right next to the worker at a factory sit-in.

Mario Merz. Sitin runs until September 16, 2018 at Fondazione Merz, Turin.