40 years after she packed them away in storage, we sit down with Donna Gottschalk to unearth her memories and photographs of her nearest and dearest

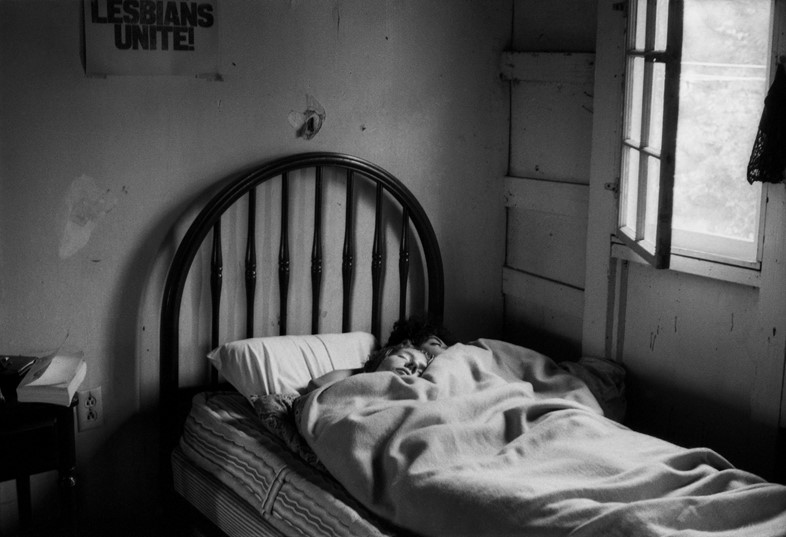

Growing up in the city’s Lower East Side, Donna Gottschalk came out just as early activist groups such as the Gay Liberation Front were forming. While an art student at Cooper Union, Gottschalk used the school’s silkscreen shop to print ‘Lesbians Unite’ posters and stencil ‘Lavender Menace’ on T-shirts.

After seeing the exhibition of Diane Arbus’ work held by the Museum of Modern Art just after that artist’s death during the early 1970s, Gottschalk recognized the power of photography to preserve the people she held closest to her heart. She began to take intimate photographs of her friends, family, and roommates with an intuitive understanding that one day, this would be all that would remain of them.

Tragically, many of those featured in her work met with early deaths, including two of her siblings. To cope with the loss and protect the memories of those she loved, Gottschalk packed up the photographs and put them in storage for 40 years. It is only now, as she approaches 70, that she has delved back into her archive to reflect on the incredible people at the forefront of the Gay Liberation Movement from the late 1960s throughout the 70s.

In Brave, Beautiful Outlaws: The Photographs of Donna Gottschalk at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York, we meet those Gottschalk knew and loved, including Alfie, her childhood brother who transitions into Myla, her adult sister, just prior to her death from an AIDS-related illness. Here, Gottschalk takes us back to a pivotal time in history, as a new generation of activists transformed the conversation around sexuality, gender, identity, visibility, and representation, giving us an intimate glimpse into their private lives.

On growing up in New York’s Lower East Side...

“My mother had a beauty parlour in the neighborhood that she opened in the early 1950s. She had always been very independent. My father was banished from the house; he was too violent. But when she got in her 40s, it was hard times in the neighborhood. We moved a lot, always fleeing higher rents.

“My mother always augmented her income by having a boyfriend, but she never moved anyone in. I would shoot photographs when it was my mother, my aunt, and my sister trying to cope with a table full of people she had to entertain, her Mafia boyfriends’ people – they were all stuffing their faces. That was everything I was rejecting in life, falling into the role.”

On becoming a photographer...

“I wanted to photograph my own people, the people I loved. They would ask, ‘Why do you want to take a picture of me? No one has taken a picture of me before.’ I would tell them they were beautiful because they were. They were magnificent. Also, it was like death was around every corner. I knew. I could see that most of my friends were going to die, and I wanted to take their picture so that when I got old, I would be able to remember them.”

On becoming an activist...

“I didn’t have much choice because being gay made me tough in school. I wanted to do better – I wanted to get fuck outta New York. I wanted to be an artist. I did well in school, got a scholarship and went to Cooper Union. By then I had my own place because my mother’s house was too chaotic. I wanted to be free, to come and go late at night without anyone asking me what I am doing. I only moved a couple of blocks away. I had all gay roommates. They were friends I met in bars.

“Gay bars were the only place you could be more or less yourself, and it was still very crippled because it was Mafia controlled and very butch/femme. But I was lucky, on the tail-end of that. It started changing within a few years of me going to the bars and then the Gay Liberation Movement started. The first march happened. People were able to congregate in clusters where they felt safe.”

On keeping memories alive...

“If I don’t share the photographs now, people will be lost and they shouldn’t be. One particular woman, Marlene, was one of my first roommates, and when she died, she had nothing. No family. She was homeless and insane. She was living in California and I couldn’t find her. I tried for the last five years but it was impossible because she was living in her van moving from place to place. With history – poof – it’s like they never existed. But that’s not true; they were buried in time. I didn’t want to forget them.”

Brave, Beautiful Outlaws: The Photographs of Donna Gottschalk will be on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York from August 29, 2018 – March 17, 2019

![Gottschalk_01[2]](https://images-prod.anothermag.com/200/0-121-1554-1036/azure/another-prod/370/9/379301.jpg)