Michaël Borremans rattles the subconscious. His paintings, created with masterful skill in oil paint, connect with deep, often dark feelings that lurk in the collective mind. Children and animals feature heavily, evoking aspects of humanity that are repressed or warped in the contemporary world. A beautifully rendered painting of children picking up scattered limbs might prompt the viewer to uncomfortably question their own role: are they a critical witness to this atrocity or a titillated spectator? While the Belgian artist is best known for his paintings, he also works with film, and has recently played a role in Luca Guadagnino’s much-anticipated movie Queer.

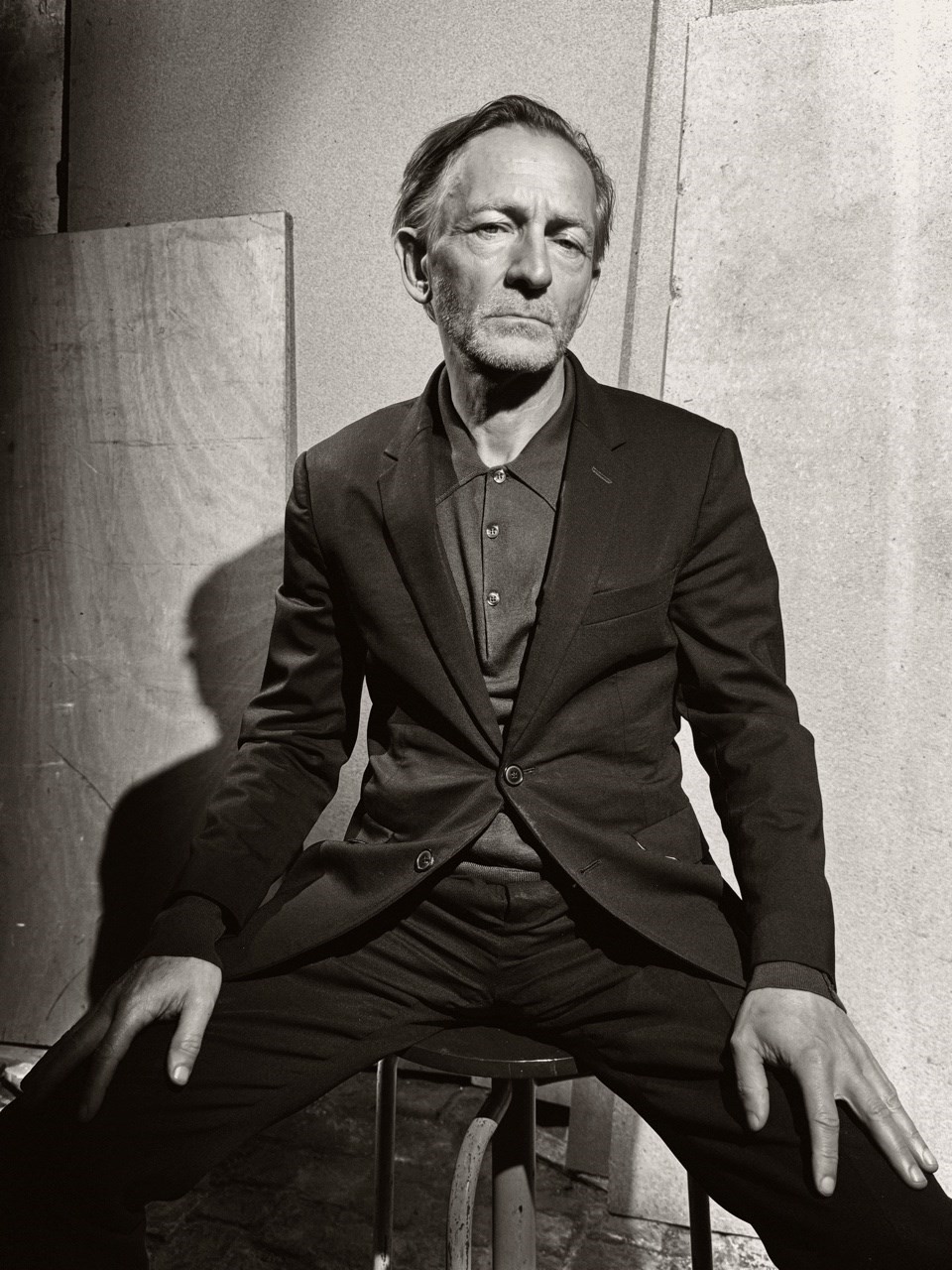

“Art is a form of implicit communication, but for me it always becomes personal,” he says, speaking ahead of the opening of his new exhibition, A Confrontation at the Zoo, at the Netherlands’ Museum Voorlinden. The survey show features two decades of painting. “When I see a work from 12 years ago, it’s like a journal. I know exactly what position I was in emotionally when I made it. Some of them remind me of tough times, others of happy times. But the cliché says that when you’re hurting, you’re making better artwork … That’s bullshit!”

Borremans embraces a host of emotions; his rich pieces combine humour, classical beauty, and chilling sadism. He is fascinated by the medium of painting and its ability to seduce or direct the viewer towards an emotional response. His technique has drawn parallels with a range of Old Masters, from Velázquez to Goya and Van Eyck. A sublime glow is emitted from many of his paintings, in the form of rosy cheeks, or golden sources of light that flicker over sinister scenes. This combination of lightness and devilry draws the viewer into a twisted dance.

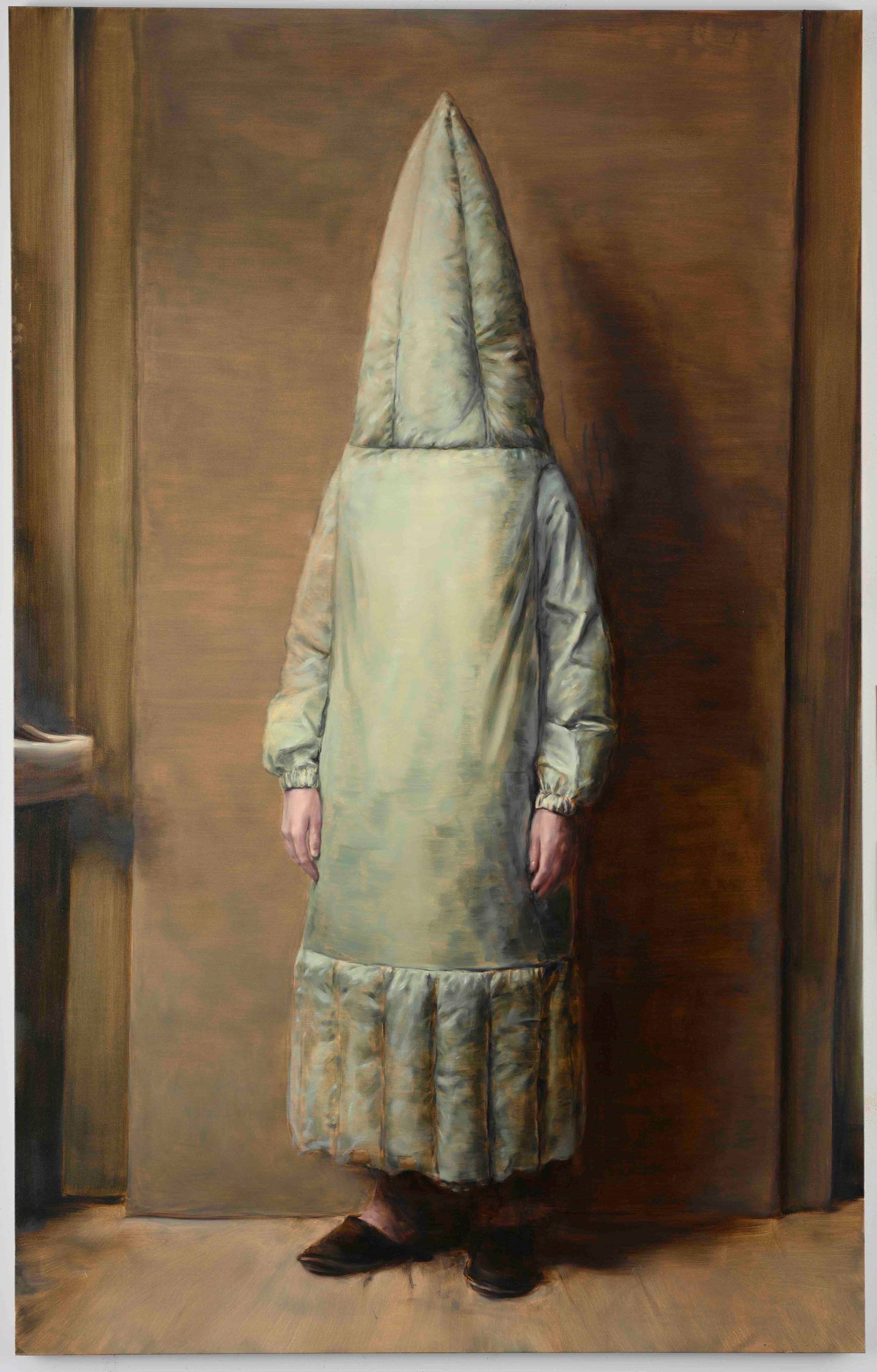

“The forms are familiar and beautifully painted, then you find disturbing or irritating elements,” he says. “Sometimes it’s overly romantic, which I like. That’s very subversive, making something beautiful into an act of perversion. I like this richness, the illusions it brings up, the way it speaks to the unconscious. That’s why a painting can stick out amongst ordinary imagery. It’s ancient, it’s primal. Showing a painting is always like a manifestation, like blowing a horn.”

“That’s very subversive, making something beautiful into an act of perversion” – Michaël Borremans

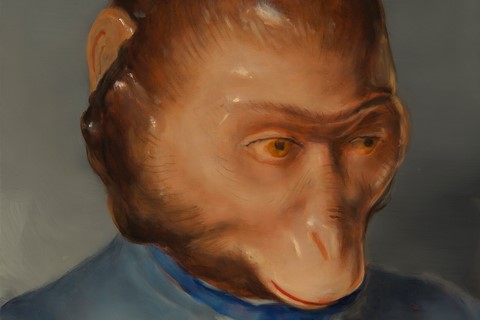

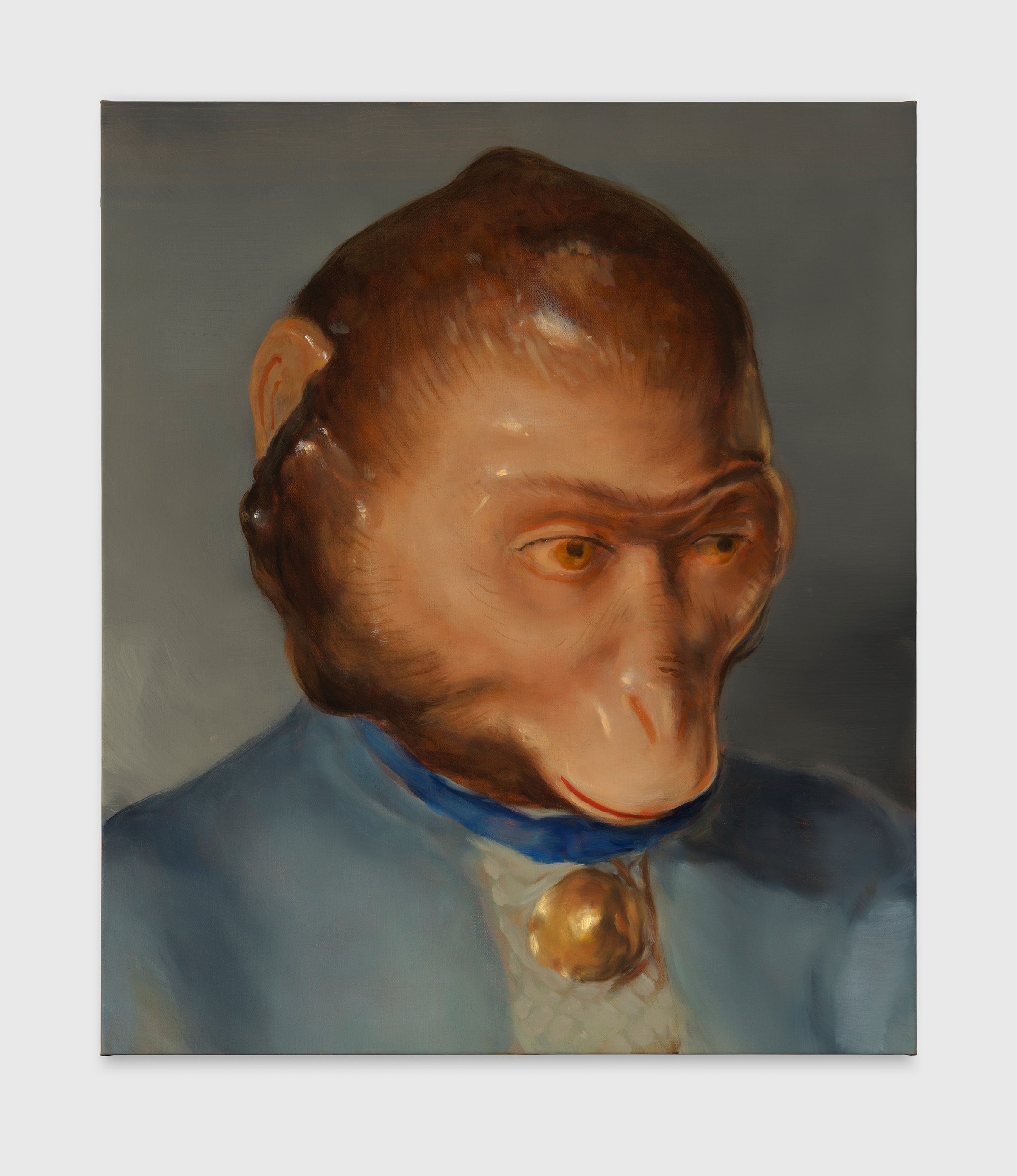

Borremans’ recent exhibition at David Zwirner in London focused on the figure of the monkey. It’s a creature similar to us yet so different, representative of a wild nature that we try hard to distance ourselves from. He notes that the monkey in the exhibition ended up looking more human than the humans themselves. Painted from a miniature porcelain ornament that he found online, its surreal glazed face shines in the final work, with a lifelike glint in its eye.

In his research, he found numerous toy monkeys dressed in human clothes or playing musical instruments. This anthropomorphism is “a way to accept ourselves as animals subconsciously,” he says. “We are the only species that is not capable of living in harmony with nature. We think we’re superior, but we’re inferior. We don’t have respect for other life. It’s very disturbing to think about.”

His famous painting of children picking up severed limbs comes from a 2018 series Fire from the Sun. In 2024, the works feel horrifically relevant, as we see countless photographs of bombed and mutilated bodies online, many of them children from Gaza. He was originally inspired to make the paintings in response to the contemporary drive for constant economic growth, which has little regard for human casualty and is inherently linked with the machine of war.

These pieces subvert the classical depiction of cherubs and chubby babies that proliferate Western art history. “It’s still disturbing but it’s also beautiful in a painting. I wanted to amplify this disturbance by showing it in the midst of innocent children.” The pieces also connect with something darker from childhood, again leading viewers to the lesser developed parts of adults that perhaps drive such barbarity. “Children can be extremely cruel,” he says. “They can be crueller than a lot of adults because they are emotionally undeveloped.”

These works have caused intense audience reactions, which Borremans welcomes. In 2022, he was caught up in the Balenciaga controversy when his book As Sweet As It Gets was used in the background of an ad that was accused of promoting child exploitation. He says the conversation quickly spiralled into conspiracy online, with some claiming he was a writer specialising in cannibalism. “People were sending me messages saying, ‘I’m so worried about you! Be strong.’ For me, it was the best thing. Finally, they see me as a subversive artist. I’m not ungrateful.”

While this online firestorm could not have been predicted by Borremans, he does think carefully about the emotional impact of his work. “The act of painting is a studio thing and a struggle in itself,” he considers. “But showing a painting is the real performance. It’s a psychological game. You place your work in a certain context and calculate what it might provoke in the viewer. There is a constant evolution in culture. We live in a world in which images are determining our thinking without us knowing.”

“If we can experience life on a more poetic level, we will not be as violent, we will not be as greedy” – Michaël Borremans

Borremans avoids specific time markers. Backgrounds tend to be non-specific, and he rarely features clothing or designs that would pin his paintings to a particular era. The works’ human dynamics find relevancy in the contemporary world, while simultaneously highlighting the omnipresence of violence. “What I like in art history is that so much of the past is still present,” he says. “It doesn’t exist anymore, but there is evidence, and most of it is held in art, architecture, and literature. The political world underestimates education and culture. The poetic attitude in society is sometimes missing but people are hungry for it. Our connection with the past, and its evidence in culture, is necessary.”

He recognises that this loss of connection with education and culture is likely happening by design rather than neglect, something that has become even more urgent in light of the recent US election. “It can prevent us from a lot of evil, if we are more educated. If we can experience life on a more poetic level, we will not be as violent, we will not be as greedy. Otherwise, people are addicted to hamburgers and television. That’s not what we want, but it’s the way we are going.”

A Confrontation at the Zoo by Michaël Borremans is on show at Museum Voorlinden in Wassenaar, the Netherlands until 25 March 2025.