“Humour is our anger management,” chuckles Michael Elmgreen over coffee in a room adjoining the Whitechapel Gallery’s café. Elmgreen and his creative partner Ingar Dragset, who have collaborated together since 1995, are about to unveil a new major exhibition of their work at the institution that evening. “The title of the show is This is How We Bite Our Tongue,” the artist continues. “And this is partly how we bite our tongue; to look at the world in a humorous way in order not to fall into a deep depression or go out and just simply scream. You can use humour in speaking about very serious matters and it becomes bearable – also for the audience.”

Indeed, Elmgreen & Dragset, as the Scandinavian pair are collectively known, are renowned for their use of black comedy to explore social and sexual politics and the power structures hidden in domestic and institutional spaces. Spanning sculpture, architecture and design, the duo is perhaps most famous for their work Prada Marfa (2005), in which a replica of a Prada store – displaying pieces from the Italian fashion house’s A/W05 collection – was permanently installed in the middle of the Texan desert. Built from biodegradable adobe bricks, Prada Marfa was designed to disintegrate over time; the door was sealed shut, never to be opened.

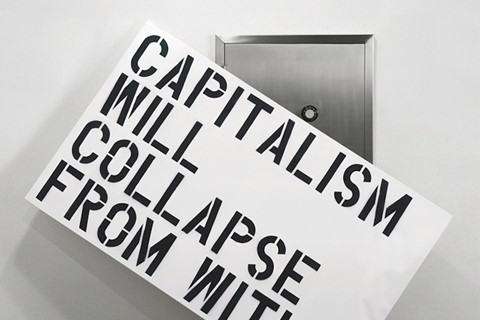

It is similar, aesthetically deceptive installation-based work that Elmgreen & Dragset bring to their new London commission, transforming the centre of Whitechapel Gallery into the exact likeness of an abandoned swimming pool, complete with slippery tiled flooring and various detritus strewn on turquoise-painted plaster. “When we come into an art space we often look at the architecture, look at the features in the space. These features often inspire us to think a certain way. Then we look at the surroundings of the institution, how the institution interacts with it, or doesn’t it interact with it. And we found that the Whitechapel Gallery is in the middle of an area that’s on the cusp of gentrification. We think it’s interesting to see what happens to our shared spaces that can be brutally neo-liberal or influenced by very strong capitalistic interests,” says Dragset.

The Whitechapel Pool (2018) is accompanied by a fictional narrative dreamt up by the artists, exploring its history from philanthropic conception in the 1900s to its eventual closure under a commercially driven scheme. Aforementioned detritus includes a piece of wood with a slug crawling up its splintering surface, a Thermos cool box and car seat – relics of summer holidays, perhaps, when the public pool enjoyed a more socially prosperous time. But on closer inspection, capitalism remains omnipresent. “The car seat is made in bronze, so it’s not just a readymade car seat. Even the wooden sticks holding it are cast in bronze. It’s a car seat from a Mercedes CLA AMG which is kind of the ‘poor man’s dream of a luxury car’,” explains Elmgreen. “In abandoned spaces, you often find leftovers, that had to do with theft or some illegal businesses or people dumping things that are not in use anymore. It is also inspired by the old Janis Joplin song: ‘Oh Lord won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz, my friends all drive Porsches, I must make amends’.”

Poolside, there is also a large silver meteorite, seemingly fallen out of the sky directly onto a trampoline, titled Too Heavy (2017). “The trampoline is being held down by the meteorite – it’s now malfunctioning. It’s never going to be bouncing again. It is maybe also talking about culture surrounding the body today,” says Dragset. “We live in a time where the body has just become decor in a way. We don’t really use the body in labour; it’s automated, something to dress or to decorate to exist in the digital world.”

“We didn’t even have an email address when we started, you know,” says Elmgreen of how the rise of technology has affected their own practice. “It was just ‘elmgreenanddragset@aol.com’. We’d check it now and again. Today, social media, in particular, provides big opportunities for people to speak out also and to communicate with each other. But it also includes a lot of dangers because everyone can post a lie – and if you do it many times it becomes a truth, which is part of the problem. There’s also a way of communicating that excludes a lot of experiences, compared to meeting together. For us, it’s important to highlight how vital being together in a physical bodily way is. And that has to happen, for a big part in public spaces. Therefore it’s a disaster that a lot of civic spaces have been closed down by the government, because they don’t really appreciate people coming together – in places such as clubs, public pools and small libraries.”

Elmgreen & Dragset also chose to install their 2010 ceramic sculpture Gay Marriage in The Whitechapel Pool: two Duchampian urinals, with silver pipes intertwined in a kind of embrace, alluding to the secret liaisons of homosexual men in public bathrooms or the toilets of nightclubs. “It’s a comment on queer relationships today, but in this context, it can also be looked at as a reference to a time where men who were interested in other men had a possibility to meet in a sort of hidden way in public,” says Dragset. “It was out of a domestic setting and it is where many subcultures developed. Teenagers have a particularly hard time because they’re not allowed to have their youth culture for very long before it’s snatched up by social media and becomes commodified.”

Certainly, with rampant gentrification comes the inevitable closure of DIY, queer spaces; earlier this year it was reported that LGBTQ venues in London had nearly halved in number in the space of just over a decade, and Elmgreen & Dragset intend to further explore this in an upcoming project. “We have recently created a reverse bar, that we will to show in the National Gallery in Singapore,” says Elmgreen. “The bar stools are trapped inside a bar that is enclosed and the beer taps are pointing out to the audience so there are no more guests in the bar. That was inspired by so many bars and pubs and places being closed down in cities like London. I mean even when I was living here, all the spots where artists would meet friends or gay places were closed down. And really, for a big part of it, I think social media has become a poor substitute.”

This is How We Bite Our Tongue is open at Whitechapel Gallery until January 13, 2019.