With a selection of her photographs on show in Edinburgh, a look at some of Francesca Woodman’s most arresting work: a series of self-portraits with eels, taken in Italy in the late 1970s

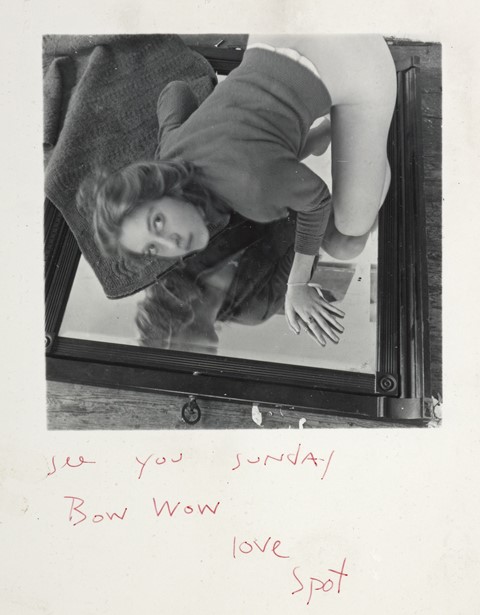

In 1978 on a hot sunny day, a 19-year-old Francesca Woodman browsed the market stalls in Rome’s Piazza Vittorio; it was here she decided to buy a bunch of live eels. With help from her roommate Sloan Rankin she carried the writhing bodies back across the ancient city to their apartment on Via dei Coronari. The two were enrolled as students at the Rhode Island School of Design’s European Honors programme, and would often spend their time roaming along the banks of the Tiber down to the Porta Portese flea market; Piazza Vittorio was also a happy habit. It was with her unusual bounty of eels that Woodman would go on to create some of the most striking and enduring photographs of her fleeting career (the artist committed suicide at the age of 22), which are now on show in Edinburgh as part of a group photography exhibition, ARTIST ROOMS Self Evidence: Photographs by Woodman, Arbus and Mapplethorpe.

Before the eels, Woodman had bought fish for her art. It was at this regular spot where she would buy fresh produce, live props with which to play. Wandering along the stands she’d ask – in her fluent Italian – for the long silver bodies and large fresh lemons that caught her eye. These ingredients featured in her earlier series Fish Calendar — 6 Days (November 1977), a gift she presented to her friend Giuseppe Casetti. Casetti hosted Woodman’s first exhibition in Rome in his Maldoror bookshop, and when asked about Woodman he would often recall how her bag was always full of strange tools, food, and jokingly: “stinking fish”.

Created over the span of a week in early March, Fish Calendar acts as a time lapse of sorts: fresh lemons appear to peel themselves and smooth wet fish multiply before the camera’s gaze beside Woodman’s naked body. The props proved useful not just for their pleasing aesthetic sheen, but for their transient nature, their ability to gently transform on demand as the bodies of the fish gently rot, the lemons wilt and their skin peels. These aspects of age feature prominently in Woodman’s work in other areas too; one only has to think of the peeling plaster on the abandoned pasta-factory walls where so many of her images were captured during her time in Rome. Age and its ability to gently expose, and the unpredictable nature of living things, were things Woodman wanted to capture.

It wasn’t a giant leap to move from buying fish to eels, but the aesthetic shift to the smooth winding bodies poses new questions. The significance of why Woodman chose eels remains a mystery, yet a look at her studies and her fascination with Surrealism and the importance of symbolic objects helps illuminate their potential connotations. Traditionally the eel’s elongated body has been linked to phallic male energy. In Italy, as in many parts of the world, eels are prized for their sweet taste, valued as expensive delicacies since the elaborate banquets of the Romans. There are tales from ancient Rome detailing certain noblemen who would feed slaves to eels, and equally tales of aristocrats who would pet them and adorn them with precious jewels; one even fastened earrings to the dorsal fin of her pet eel, another garlanded his with small necklaces “just like some lovely maiden”. Predators whose (uncooked) blood is poisonous to humans, eels are creatures with a rich history. Feared, yet also revered: a delicious dish, an adored pet.

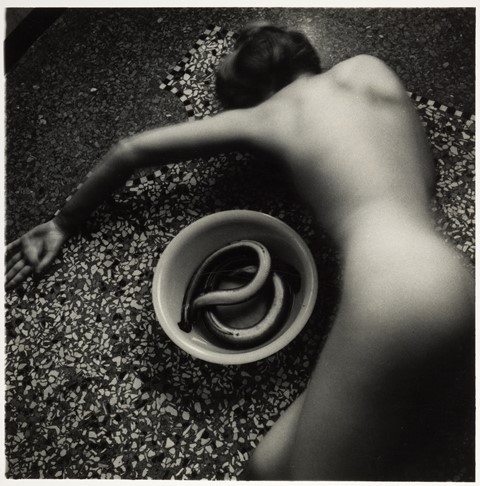

On one of her frequent trips to Venice, perhaps to see the Biennale that year in 1978, Woodman stripped down to produce her eel images on a broken terrazzo floor. Her body wraps itself around the creature, her arms and legs both blurred into imitation as her form becomes a single swooping arc. In the sequence her body shifts like an eel itself, slithering around the bowl in which the eel lies. She is shown from every side: first from the left, above, and then the right. Her naked back to the camera, she becomes quasi-sexless, more animal than female. The writer Deborah Levy once noted that Woodman had essentially created an “uncanny language to unknot the ways in which we are encouraged to gaze at the female body”. This language allows us to re-evaluate the female form by looking to the natural world and asking what we are made of.

In these pictures, Levy’s term “unknot” takes on renewed significance, located directly in the ropey bodies of those water creatures Woodman collected from the Roman and Venetian markets. Do the muscular eels present a symbol of some great binding masculine power that wishes to tie the female body, to contort it, or keep it captive? Are they a manifestation of Woodman’s own desire? Since her body is both passive and active, the ropes that would tie her limp and cold, coiled in an enamel cooking bowl, you wonder whether she acts as predator or protector of the eels? As with so much of Woodman’s work, the fascination lies in the unknown.

ARTIST ROOMS Self Evidence: Photographs by Woodman, Arbus and Mapplethorpe is at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, until October 20, 2019.