As Pedro Almodóvar’s art-filled Pain and Glory arrives in cinemas, we look at the modern art which has appeared in his films – and what it means

In Bad Education (2004), wearing white briefs that barely conceal his modesty, Mexican actor Gael García Bernal dives head first into a resplendent swimming pool at dawn. It is a scene which echoes the erotically charged paintings of swimming pools by David Hockney, Peter Getting out of Nick’s Pool and Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) among them.

Modern masterpieces such as these have always stirred something in director Pedro Almodóvar. Compositions by artists such as Hockney, Edward Hopper, René Magritte and Piet Mondrian have inspired iconic tableaus in many of his films, as have religious and mythological scenes from Renaissance and Neoclassical paintings. But nothing offers quite so close a look at Almodóvar’s taste in art as his new film, Pain and Glory.

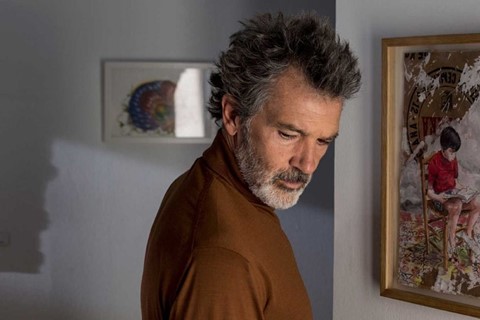

This is the director’s most autobiographical work to date: the home of the protagonist, Salvador Mallo (played by Antonio Banderas), is a near like-for-like replica of Almodóvar’s own apartment, and it offers an intimate glimpse of his impressive art collection. “This looks like a museum!” exclaims long-lost friend Alberto (Asier Etxeandia) when he walks into Salvador’s home.

Look closely back at Almodóvar’s other movies and you will find that they provide galleries for paintings and sculptures by contemporary artists, which the filmmaker has carefully curated as part of his visual language. Slick and powerful in their placement, these artworks nudge the narratives along, bringing to life the experiences, emotions and psychological conditions of the characters.

Louise Bourgeois

In the Frankenstein-like thriller The Skin I Live In (2011), Vera (Elena Anaya) is held prisoner by the plastic surgeon Dr Robert Ledgard (Antonio Banderas), who performs experiments on her body. Driven to madness, Vera scribbles across the bare white walls of her cell-like room – and at the centre of her sprawling notes are the words: “Art is the guarantee of health.”

In her solitude, Vera reads books and watches documentaries about the French-American artist Louise Bourgeois, who recently became the world’s most expensive female sculptor, with one of her bronze spiders selling at a record price at auction. Just like Vera herself, Bourgeois’ visceral human figures are masterfully moulded together, yet uncanny and disconcerting. From her black body stocking and white plastic mask to the artificial skin that Dr Ledgard applies to her flesh, Vera’s body is composed of layers that are aching to peel away. And although Dr Ledgard’s gaze projects an idealised image of Vera reclining nude like an odalisque, resembling Titian’s Venus of Urbino that hangs in the hallway of the surgeon’s mansion, Vera’s reality is far closer to Bourgeois’ distorted figure of decay.

Lucien Freud

Based on a book by Canadian author Alice Munro, the film Julieta (2016) tells the story of female silence. While Julieta (Emma Suárez) stands alone in her apartment rummaging through the scraps of a life she has tried for so long to escape, a self-portrait by Lucian Freud hangs on the wall behind her. “I prefer to be alone,” she says soon after to her partner, Lorenzo (Dario Grandinetti).

Freud’s self-portraits (over 50 of which will be exhibited at the Royal Academy from October) offer a penetrating, devastating form of introspection. The almost uncomfortably raw realism of his work presents an analysis of the psyche that recalls the artist’s grandfather, Sigmund Freud. As Julieta looks inward trying to piece together the fragments of her broken past, the tormented, solitary painting underpins her suffering – and the presence of such a distinctly male portrait serves to further isolate Almodoóvar’s already broken heroine.

Twists on classics

In Pain and Glory, the Guggenheim museum requests to borrow a painting by Guillermo Pérez Villalta from Salvador Mallo’s private collection for a retrospective they are planning on the artist. But Salvador declines: “Those paintings are my only company,” he says. “I live with those paintings.” The work in question is Artista viendo un libro de arte – and it forms the backdrop of Salvador’s heart-wrenching re-encounter with an old lover.

Pérez Villalta has known Almodóvar for around 40 years and his works have appeared in films as early as Pepi, Luci, Bom (1980) and Labyrinth of Passion (1982). In The Skin I Live In, his painting Dionisios encuentra a Ariadna en Naxos depicts figures of classical mythology but with eerie faceless spheres replacing their heads. In its postmodernist refiguring of the ancient Greek characters, the piece nods to the masterful twists on classic tales which Almodóvar employs throughout his work.

Tributes to post-Franco Spain

In Bad Education, two old school friends are reunited after decades apart. Hanging on the wall behind them during their tense but tender re-encounter is a painting by Sigfrido Martín Begué called La máquina de hacer cine. The same artist returns in Pain and Glory, with the paintings Las costureras and El olfato – Santa Casilda hanging on the protagonist’s art-filled walls.

Martín Begué was one of Almodóvar’s contemporaries during the movida madrileña, Spain’s post-Franco movement of artistic, social and sexual liberation in the early 1980s. With Martín Begué and others like Miguel Ángel Campano, Dis Berlin and Manolo Quejido, Almodóvar’s art collection acts as an homage to a generation of artists from this pivotal period of modern Spanish history, from which the filmmaker himself emerged as one of the greatest stars.

Art he wants to buy

While Almodóvar’s art collection is something of a who’s who of Spanish postmodernism, there are certain artworks that he is yet to get his hands on. In 2017, during an exhibition of the Spanish surrealist painter Maruja Mallo at Guillermo de Osma gallery in Madrid, Almodóvar confessed that he wished he had acquired the painting El racimo de uvas before the gallerist had. Either way, there it hangs in the kitchen in Pain and Glory.

Mallo was a key figure in Spain’s Generation of ‘27 cultural movement and a peer of Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Max Ernst and Joan Miró. She is famously one of Almodóvar’s favourites – his fixation with her is evident in the stylistic similarities of his own Vida Detenida series. And in his new film, it is perhaps no coincidence that his protagonist, and alter ego, carries the artist’s surname.

His own art

Unlike the showy collection on display at Salvador Mallo’s apartment, the most intriguing artwork in Pain and Glory is far more modest and understated – an evocative watercolour that contains a lifetime of desire, sorrow and memory, but whose humble creator would never live to see the impact it would have.

The real artist behind the work is Toledo-based painter Jorge Galindo. Although his identity is obscured in the film, his off-screen relationship with Almodóvar has proved fruitful: the director has created artworks alongside Galindo, with the results of the pair’s collaboration currently on display at the Centro Andaluz de la Fotografía in Almeria.

This is not the first time Almodóvar has tried his hand at creating art. Back in 2017, while writing Pain and Glory, he produced a series of still-life photographs called Vida Detenida, which have been exhibited by Fresh Gallery and Marlborough Gallery. The images are fiercely realist but with colours and compositions reminiscent of pop art. In the new film, as Salvador Mallo desperately tries to ease his suffering, Almodóvar’s own still-life photographs hang behind him, a reminder of the director’s deeply personal presence in the film.

Pain and Glory is in UK cinemas from August 23, 2019.