Yoan Capote, whose exhibition Omitted Subject is open now in Italy, speaks to Harry Seymour about his unique journey as an artist in his home country of Cuba and beyond

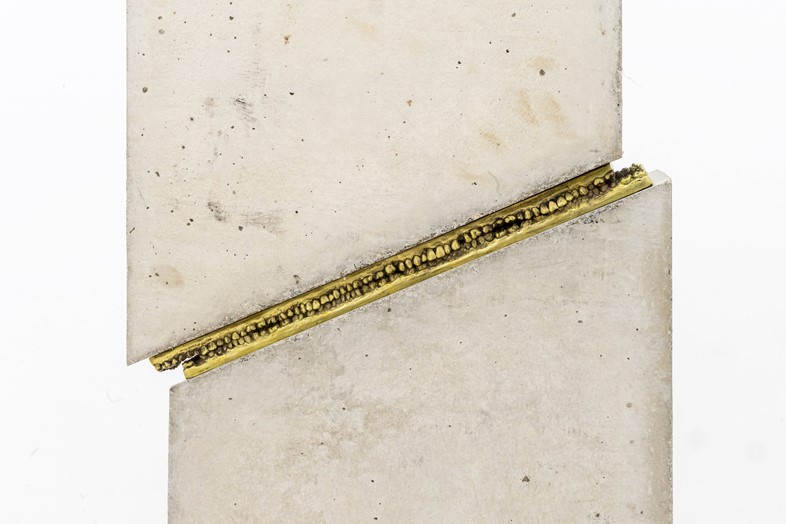

Cuban artist Yoan Capote (b. 1977) has represented his country at the Venice Biennale, won a UNESCO prize and received a fellowship grant from the Guggenheim Foundation – all for his political paintings and sculptures that bend fishhooks, spell out words in sign language and grate cast-gold teeth between concrete blocks, among others.

At the opening of his first solo show in Italy, Omitted Subject, in the hilltop town of San Gimignano in Tuscany, Italy, at Galleria Continua, we sit down with Capote to hear about his journey from a rural farm in Communist Cuba to becoming an international success, along with the struggles that artists in his home country can face.

Harry Seymour: What was your journey to becoming an artist, and what does the infrastructure look like in Cuba for young artists?

Yoan Capote: It has changed a lot, but back then the government implemented a lot of support for culture. When I was around ten, I started taking art classes in school. These programmes were supported by Russia and China, the Socialist places. We received a lot of political teaching. A strong approach came from the Russian professors, but it was good for discipline. The plan however wasn’t for us to become international artists. It was to finish school, return to the countryside and spread culture. When I finished school, however, the Russians began leaving, and the educational system was collapsing.

HS: When was this?

YC: Around 1991. Then I was selected to study at the National School of Art in Havana. Each year the government would select ten or 15 students from across all provinces.

HS: Was there a test?

YC: Yes. My friends would be playing soccer or with girlfriends, but my father would warn me if I did that, I would have his destiny, growing rice. It’s hot, hard, muddy work. He explained that he knew nothing about art, but that he hoped it meant I didn’t have to do that. So I would draw in the bathroom every night until 3am, then wake up for school at 8am.

HS: It paid off?

YC: Yes, I arrived in Havana, but the government didn’t have any money to maintain the free art school and the director told all the students that it was going to be tough and there wasn’t enough food – but those who wanted to stay would be given the freedom to make it work.

HS: Did it stay free?

YC: Yes, but the teachers emigrated to further their careers. That made me start to realise that I could make a living from art. I used to sit on a wall imaging what was beyond the horizon.

HS: America?

YC: Yes – something is rooted in Cubans about America. Everyone always talks about it. I started learning about art from books in the art school, which expanded my dreams of America.

HS: What happened after art school?

YC: My work was chosen for the Havana Biennale, where it was awarded a prize by UNESCO. In 2000, I realised that I didn’t want to stay in Cuba and be a professor, so started to apply for fellowships.

HS: Where?

YC: In Cuba. I started using the internet in a hotel lobby which cost me ten dollars an hour. I applied for fellowships, then a piece of mine was selected to show in Germany. It was seen by an American lady who asked me how I made it. I explained that because I had no money I cast it myself, illegally in a government foundry, crossing the fence at night. She then paid for me to go to Vermont for a fellowship.

HS: Was it easy to leave Cuba for Vermont?

YC: Luckily I received a visa, but the process is completely random. There was an American couple who had given me their card in Cuba and wanted to buy my work, but I had no idea what to charge. I said “it’s a gift”. They offered me 9,000 dollars – more money than I had ever seen. I said I didn’t want it, but could they help me to emigrate. They said I was crazy, and that being in Cuba was right for me. They told me to go back and set up a studio. They still gave me 9,000 dollars which I used to visit New York and buy books. Then I returned to Cuba and set up my studio.

HS: How did you get your first gallery deal?

YC: I was told by the American couple never to approach a gallery, but instead wait to be discovered. In 2009, I was participating in the Havana Biennale and a man came to my studio and bought something, then told me he was actually a dealer in New York, and he wanted to do a solo show of my work at his gallery. I said “You are the person God has sent, just send a date and a gallery plan”. That was my first major solo show in New York in 2010.

HS: How did you come to work with Galleria Continua?

YC: When they opened their space in Havana it was a breath of fresh air, bringing international art to Cuba. One of the founders came to my studio and invited me to participate in a show at their gallery.

HS: Is it good commercially?

YC: I ended my deal with my old gallery because the owner was only interested in meeting the financial quota set by the government. Now I just have my studio and pay my taxes. I also have nothing to do with the Biennale anymore, after they told me I had taken part too many times. I explained it should be about the quality of the art, not politics.

Yoan Capote: Sujeto Omitido (‘Omitted Subject’) is on at Gallery Continua in San Gimignano, Italy, until January 6, 2020.