A mammoth new book titled Japanese Woodblock Prints, published this week by Taschen, explores the storied history of the art form via 200 exquisite prints

The advent of woodblock printing in Japan dates back as far as the eighth century, and reached the height of its popularity during the country’s Edo period, from the 1600s to the late 1800s. The meticulous art form – which involves an artist designing an image, a carver chipping away the design in a block of wood, and a printer transferring the image from the wood to paper – has become a defining aspect of Japanese art, and has long provided inspiration for artists the world over. A new Taschen-published tome – one of the German publisher’s XXL editions – titled Japanese Woodblock Prints offers a comprehensive look at 200 seminal woodblock images and the prolific artists who created them between 1680 and 1938.

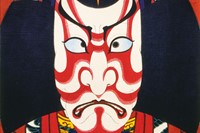

During these years, woodblock printing became democratised as images were reproduced both in books and as single prints in multiple editions, and the artworks could be affordable, widely circulated and entertaining. Ukiyo-e images – a genre of printing and painting, the name of which means “pictures of the floating world” – would often depict scenes of society and socialising in Edo (now Tokyo), where people would attend Kabuki theatre, watch dancing and encounter geishas. The printing techniques, colour palettes, distinctive artistic style and subjects would heavily influence European painters of the 1800s – falling under the umbrella term of japonisme – like Manet, Degas and Van Gogh. “I envy the Japanese for the enormous clarity that pervades their work... they draw a figure with a few well-chosen lines as if it were as effortless as buttoning up one’s waistcoat,” the latter artist once said.

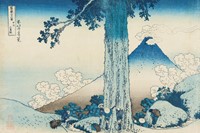

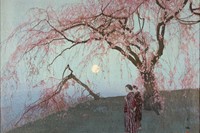

The 200 prints showcased in Japanese Woodblock Prints were compiled by Andreas Marks, and are revealed chronologically, tracing the peaks and troughs of woodblock printing’s popularity. The artists featured are still some of Japan’s most recognised names: Hokusai, of The Great Wave fame, Hiroshige, renowned for creating exquisite woodblock depictions of everyday life in the country, and Moronobu, who is credited as the founder of ukiyo-e in Edo, among others.

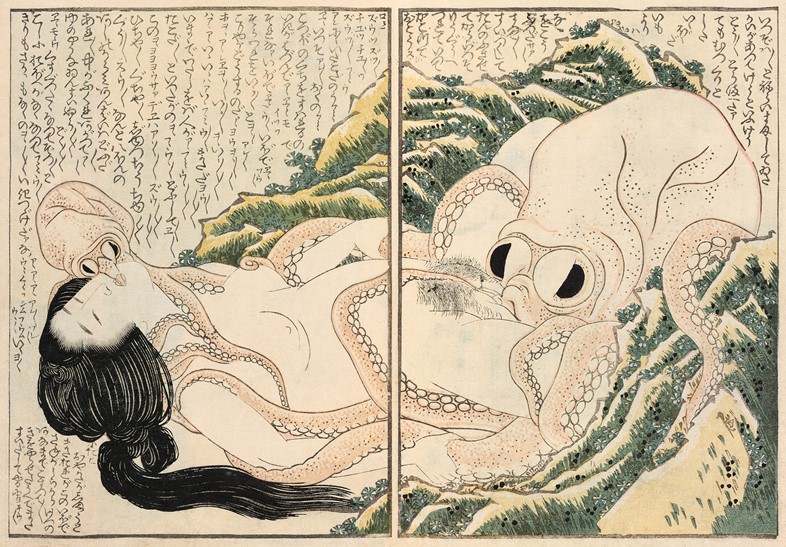

Similarly, the prints’ subjects range from the sensual to the sublime to the subversively humorous: beautiful, sakura-filled landscapes might morph into a skeleton-filled dreamscape (with snarling characters and scenes making for sometimes unsettling viewing); lovers might be caught in a tender embrace, or sneaking an illicit look in a nearby mirror. Erotica was a popular subsection of ukiyo-e prints, and was often shared between couples and friends as a source of both entertainment and pleasure. Hokusai, who is remembered for his landscapes but was equally prolific in shunga (the Japanese term for erotic art), created one of the most famous examples of tentacle erotica in the history of art: The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, 1814, depicts a tryst between a woman and two octopuses. In Japanese Woodblock Prints, the fascinating history behind 200 of the most enduring prints is placed firmly in the spotlight, to captivating effect.

Japanese Woodblock Prints by Andreas Marks is out now, published by Taschen.