As an exhibition of her early work opens at Guggenheim Bilbao, we explore the formative years and enduring legacy of Lygia Clark, the Modernist artist who broke down the barrier between art and life

Who? Brazilian artist Lygia Clark (1920-1988) was a radical pioneer of contemporary art who spent her professional life pushing at the very boundaries of what art could and should be. In the first half of her career, she played a key role in the geometric abstraction, Neo-Concretist and Brazilian Constructivist movements, before going on to champion participatory art, exploring art’s therapeutic potential as a means of tapping into sensory memory. “We do everything so automatically that we have forgotten the poignancy of smell, of physical anguish, of tactile sensations of all kinds,” she famously said.

Since her death, Clark has been celebrated in a number of international exhibitions, including a major retrospective of her work at MoMA in 2014, which have firmly established her far-reaching artistic legacy. Now, a new show at Guggenheim Bilbao, titled Lygia Clark: Painting as an Experimental Field, looks to shed light on a lesser-known, but nonetheless vital, period of her work: the first decade of her artistic output, spanning 1948 through 1958. During this time, Clark developed many of the ideas and stylistic traits that would come to define her later work – in particular her innovative determination to create so-called “dynamic environments” through art.

What? The exhibition, which inhabits three rooms of the visually arresting Frank Gehry-designed museum in the centre of Bilbao, is split into three corresponding sections, each dedicated to a significant shift of direction in Clark’s artistic practice during her formative years. Clark had an unhappy childhood – she never felt accepted by her repressively bourgeois family, and from a young age took to drawing as a means of escapism and self-expression. When she was just 18, she married a civil engineer named Aluízio Clark Ribeiro, and relocated from her hometown of Belo Horizonte to Brazil’s then-capital, Rio de Janeiro. By the age of 25, she had three children and could no longer resist the desire to create.

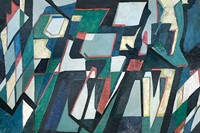

In 1947, she began training under the Brazilian Modernists Roberto Burle Marx and Zélia Ferreira Salgado, taking on traditional subjects in charcoal and paint, while demonstrating her innate interest in what curator Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães terms “vernacular colour, stylised form, and flattened space”. A passionate fan of Piet Mondrian and Paul Klee, in 1950 Clark opted to spend two years in Paris under the tutelage of Fernand Léger and Árpád Szenes. There, her work took a more abstract turn, as evidenced in various architectonic graphite works from the time and beguiling geometric paintings with a chromatic, modular bent.

When she returned to Rio, she was initiated into the artist collective Grupo Frente, connecting and exhibiting with fellow avant-garde artists such as Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Pape. Between 1953 and 1956, she continued to pursue geometric abstraction, cultivating her own sensuous, delicately coloured vernacular within the movement as it took hold in Brazil. Simultaneously, she began to challenge the spatial conventions of the image plane in series such as Breaking the Frame (Quebra da moldura, 1954), which integrated the frame into the body of the painting to render it a three-dimensional object and saw the artist replace oil paint and canvas with industrial paint and wood in the process. She also produced a beautiful series of maquettes at this time, decorating imagined interiors to demonstrate her ideas surrounding dynamic, art-led living spaces. “What I seek is to compose a space and not compose in it,” she said.

Why? The exhibition’s final section sees Clark take a further, important leap into the realm of art as interactive object – after this period, she abandoned painting altogether in favour of increasingly organic or corporeal sculpture, installation and performance art, and finally psychoanalytical experiences. At this point, she ditched her previously colourful approach to work in black and white, which she believed gave her greater scope to investigate the modulation of space. She produced hundreds of drawings and collages at this time, obsessively interrogating the impact of colour, space and line both internally (within the work) and externally (upon the viewer and their surroundings).

In one of the last artworks on display, 1959’s Counter Relief (Contra relevo), painting has practically given way to sculpture – the origami-esque, monochrome work comprises three planes, which are visible only by viewing it at different angles. This preempts her seminal later pieces, which aimed to stimulate the entire body using all the senses, without prioritising the visual. She described such works as “living organisms”, rendered so by human participation.

Clark was an entirely unique artist – as scholar and curator Guy Brett has noted, “her work did not borrow existing concepts of art ... on the contrary, she transformed notions of art and the artist” – and the Guggenheim show offers powerful insight into the early workings of a singular mind, determined to break down the barriers between art and life.

Lygia Clark: Painting as an Experimental Field is at Guggenheim Bilbao until May 24, 2020.