Beaton’s early photographs showed the power of artifice and fantasy in a Britain demolished by World War One

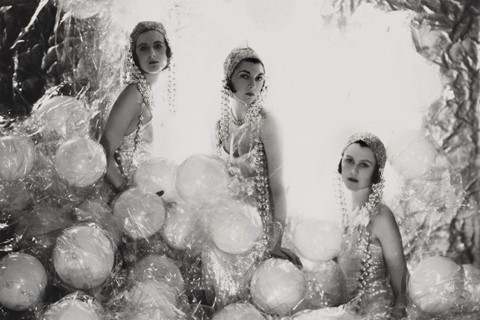

There is a pertinence to the National Portrait Gallery’s latest exhibition, Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things – currently put on hold as the entire gallery closes in response to the Covid-19 pandemic – which puts on display an extraordinary collection of photographs by the image-maker, taken during the 1920s and 1930s. Featuring luminaries of the day, from Anna May Wong, Oliver Messel and Stephen Tennant, to partygoers, high society and Beaton’s own sisters, his pictures capture the giddy and delirious creative spirit which arose out of a British society demolished by World War One.

Beaton’s was the generation who had missed being drafted, just. Born in Hampstead in 1904, he was ten when the war began, and still a teenager when it ended – and it was during this time that he first would pick up a camera, a folding Kodak 3A, owned by his nanny, taking photographs of his sisters in the family garden. He would send them off to society magazines, recommending his own work under a pen name; while attending Cambridge University in the 1920s, he would have his first photograph published in Vogue, the beginning of a decades-long alliance with the magazine which saw him capture the era’s most famous names.

That photograph was of Beaton’s university acquaintance, George ‘Dadie’ Rylands, dragged up as John Webster’s Duchess of Malfi “in the subaqueous light outside the men’s lavatory of the A.D.C. Theatre at Cambridge,” as Beaton would write afterwards. It earnt him a fee and a place in the magazine’s pages, and was an early indication of his style: swooning and romantic portraits of Britain’s thinking classes, where broad strokes of fantasy and artifice stood as a defiant rebuke to the austerity of post-war life. They were preoccupations which would follow Beaton throughout his life.

And, while most exhibitions on Beaton have been surveys of his entire career – which would also see him gain renown as a costume designer, memorably outfitting My Fair Lady – Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things instead focuses on the whimsy of these early years, culminating in his induction into what would be deemed the Bright Young Things of the 1920s. It began with his introduction to Edith Sitwell, who he would go on to photograph in her ancestral home in Renishaw, and continued with friendships with Tennant, Wong and Messel. Most famously, he captures the whole group on the lawn of Wilsford Manor, bedecked in ruffles and bows, like shepherds and shepherdesses from a Boucher painting. In the tabloid newspapers, they would become a sensation, as Beaton et al had a series of increasingly opulent – and elaborately outfitted – parties and gatherings.

But if these photographs – painstakingly gathered together for the very first time – are proof of how creativity can be spurned from tragedy, then it was to be short-lived. The Bright Young Things would succumb, as the rest of Britain would, to another World War. This time, Beaton became part of the war effort, training his lens on the conflict and destruction he had avoided as a teen. He took over 7,000 photographs of Blitz-ravaged London, and scenes of devastation across the world, from Africa to China. It is said that such photographs – particularly those of the children who survived the London bombings, clutching teddy bears and toys among destroyed cityscapes – would highlight the necessity of America intervening of behalf of the United Kingdom.

Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things, then, highlights a small glimmer of unbounded joy which arose between the devastation of two wars. Yesterday, the National Portrait Gallery closed its doors as a response to the outbreak of Covid-19. In a time which looks particularly bleak for the country, one can only hope that once the outbreak is over it will provide the impetus for a new generation of artists – like Beaton and his Bright Young Things – to enliven Britain’s cultural landscape once again.

National Portrait Gallery is currently closed due to the outbreak of Covid-19. Their website provides a comprehensive archive of Beaton’s work – for those who want to find out more, read Edward Meadham’s ode to his photography, discover ten things you didn’t already know about the photographer and designer, or head to Another Man to find out about his spectacular personal style.