This article is published as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign:

Video artist and filmmaker Charles Atlas’ back catalogue spans TV specials, semi-fictional documentaries and multi-channel installations, all connected by the power to blur performance with reality. Ominous, Glamorous, Momentous, Ridiculous, his new show at the ICA Milano – fully installed but closed to the public due to coronavirus, so available to view as a virtual tour – showcases some of his most famous works, including Hail The New Puritan and The Legend of Leigh Bowery. Technical and complex, his brand of time-based media doubles as a window onto the underground scenes he belonged to in the 80s and 90s, starring the close friends that made those radical networks famous.

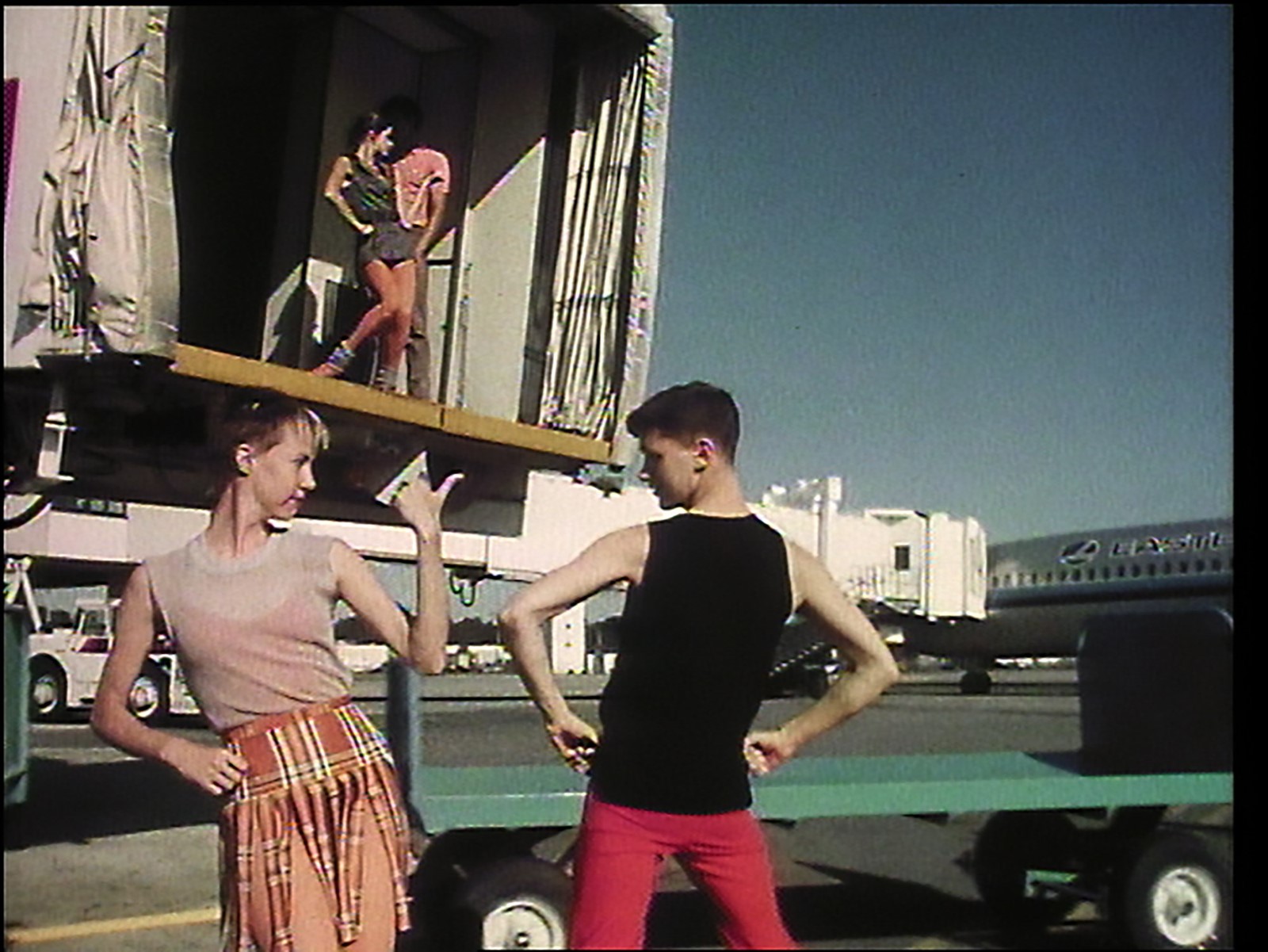

Weaving movement, identity and subversive glamour, Atlas’ video portraits hinge on the creative possibilities of collaboration. From being filmmaker in residence for legendary American choreographer Merce Cunningham’s dance company (where he started in 1969 as an assistant stage manager and later established a new art form in media-dance) and exploring the outrageous universe of artist and designer Leigh Bowery, to documenting a dream-like day in the life of mercurial dancer Michael Clark while sending up Thatcher’s dysfunctional Britain, the singular personalities of his creative partners regularly dominate the work.

His most recent piece, I Am Beautiful, was created for the Milan exhibition and combines films of women shot on stage while touring with Antony and the Johnsons in 2006 with unused footage of Bowery lip-syncing to Aretha Franklin. Another example of Atlas’ skill for composing and curating that rings just as true when repurposing these previous pieces as it does when live mixing a performance that juggles moving image, musicians and dancers from his laptop.

Currently under lockdown in New York, the genius who brought us Michael Clark dancing to The Fall in a bumless leotard discusses his attraction to artists who work at the edges of society, and the secret to collaborating with characters that other people find impossible.

Ben Perdue: What kind of films did you hope to make when you set out with your first Super 8 camera in 1970?

Charles Atlas: I had no idea. I was just working out how to use the camera and it developed from there. Then, when Merce Cunningham asked me to collaborate with him, I suddenly had to learn how to use video. Neither of us knew what we were doing, so I learnt it all from a book.

BP: Did having limited funds and equipment shape your style?

CA: Video was inexpensive to produce compared to film, and it gave us a way of working where we could immediately see what we’d done and make adjustments. We’ve been making videos together ever since, but I guess you’re always limited by what you have to work with, whether it’s space, or budget, or time. That will never change.

BP: These collaborations are so important to your work, but what drew you to underground artists like Merce Cunningham, Leigh Bowery and Michael Clark?

CA: Well, I started out with Merce because I got lucky and have been with his dance company ever since. But I was always in contact with people doing what you might call avant-garde work. I’ve always been attracted to people doing the most extreme things, and that drew me to dancers like Michael Clark, who I first worked with when he was just 20 and no one had heard of him.

“I’ve always been attracted to people doing the most extreme things” – Charles Atlas

BP: Is there a secret to keeping those kinds of long-term collaborations successful?

CA: Merce Cunningham was the best collaborator. His way of getting the best out of everyone was not telling them what to do. So, all of the collaborations that I’ve done have more or less been in that vein. I don’t really have an approach; I bring what I bring, they bring what they bring.

BP: Have there been artists you’ve admired who ended up being a nightmare in person?

CA: I’ve worked with some very difficult personalities, and I realised early on that just because I love someone’s work it doesn’t mean I should work with them. I’ve definitely collaborated with a lot of artists that other people find impossible to work with. Sometimes a successful collaboration just means letting the other person have their way.

BP: Was working with dance something you stumbled into, or had you always been inspired by that world?

CA: I really didn’t know any dance before I started working with the Cunningham company, but I worked with them for over 30 years. I was a lighting designer, costume designer, stage manager and production manager before I was ever their filmmaker. So there was never a plan, I just went from one project to another and it became a regular way to make films.

BP: But it was through dance that you developed media-dance, your form of filmmaking that merged the two disciplines?

CA: Yes. We were figuring out how to cut between still cameras placed in various positions, then we introduced another mobile camera that could move between the dancers, and it became a choreographed element of the performance. This turned into live multimedia pieces, but the filming part still never competes with or upstages the dancers and is always synchronised.

“I used to think of my work as like time capsules that related to my life and the current cultural situation, but lately I’ve found that I’m more interested in testing the limits of form” – Charles Atlas

BP: Did working behind the scenes with a dance company help when you started staging your own live performances?

CA: I still do the lighting and projections for Michael Clark’s live performances today, but all that work with Merce and other dancers on stage gave me a feel for scale, and I’ve definitely incorporated it into what I do with galleries and museums today.

BP: Protagonists like Michael Clark were very much the focus of your earlier work but as time passes do you find yourself focusing less on art scenes and more on broader themes?

CA: I used to think of my work as like time capsules that related to my life and the current cultural situation, but lately I’ve found that I’m more interested in testing the limits of forms, and things that are more universal. And since 2003 I’ve been more into performing than documenting, that was when you could first do live video processing from a laptop.

BP: So, is it important to you to keep testing what can be done with emerging technology and techniques?

CA: I’m interested in innovation. I once did a piece on this huge building called the Merchandise Mart in Chicago, its surface was something like two and a half acres with hundreds of windows, and we had to use 32 projectors. That was a big technical challenge, but I try to learn something new on every project. If you want to push yourself and not just repeat things, then you have to do something new. Now that I’m in lockdown that means learning new software.

BP: Does it amaze you to compare what you can create today with what you could in the 70s?

CA: It doesn’t surprise me. I haven’t had a Super 8 in a long time, but my house is full of video tapes and films. Not everything has been converted to digital yet because I used to do so much casual filming, but I’m not that guy who goes everywhere with a camera anymore.

BP: And were you able to try out something new for the current show at ICA Milano?

CA: In a lot of ways installing old work in a new space always feels different anyway, but this is a five-channel piece, and four of them are based on live mixes I did in 2006 when I was on tour with Antony and the Johnsons. As the band played, we had women appear on spinning platforms on stage and filmed them with two cameras. Then I would mix the feeds and project them on a huge screen behind the band. So, I’ve remixed those original recordings and synched them with a portrait piece I did of Leigh Bowery, and the finished work is called I Am Beautiful.

Charles Atlas: Ominous, Glamorous, Momentous, Ridiculous was due to be staged at ICA Milano from March 12, and will remain in the space until May 3, 2020.