Tate Modern opened its doors 20 years ago today, and has been one of London’s foremost champions of modern and contemporary art since. Here, we look back over two decades of one of its unique spaces: the Turbine Hall

This article is published as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign:

On May 11, 2000, the Tate opened its newest iteration: Tate Modern, built in what was formerly the Bankside Power Station in London. In the 20 years since its opening, the vast space has housed exhibitions and artworks by modern and contemporary art’s biggest players. Most recently, its Andy Warhol retrospective offered an immersive look at the Pop Art world of Warhol, and to celebrate its 20-year anniversary, the gallery was due to open a year-long exhibition dedicated to Yayoi Kusama featuring two of the Japanese artist’s ever-popular Infinity Mirror Rooms – both exhibitions have of course been interrupted by lockdown in London amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Turbine Hall forms both an entrance to the gallery and one of its unique exhibition spaces, marked by its annual commissions create specifically for the cavernous space. To celebrate 20 years of Tate Modern, we’re remembering ten of the Turbine Hall’s most impressive exhibitions – from Ai Weiwei’s millions of sunflower seeds to, most recently, Kara Walker’s subversive ‘historical’ monument.

Louise Bourgeois, I Do, I Undo, I Redo, 2000 (lead image)

The Turbine Hall’s first exhibition showcased work by the seminal artist Louise Bourgeois, who in 2000 was entering her eighth working decade, and still as prolific as when her career began in the 1930s. For I Do, I Undo, I Redo, Bourgeois installed three 30-feet tall steel towers in the Turbine Hall, each with spiral staircases, circular mirrors standing atop viewing platforms, and mother and child sculptures. Bourgeois’ famed sculpture Maman, of a giant spindly bronze, stainless steel and marble spider was made as part of this inaugural Tate Modern commission and went on to become one of her most acclaimed; it has been exhibited the world over in the 20 years since its creation, and was due to arrive back in the Turbine Hall for the gallery’s anniversary celebrations this month.

Anish Kapoor, Marsyas, 2002

Known for his engulfing, often gigantic, sculptures, Anish Kapoor’s Marsyas was a distinctly modern take on a Greek myth much-depicted throughout the history of art: the story of the satyr Marsyas and the god Apollo. Marsyas, after a music competition against Apollo, was skinned alive by the god as punishment for challenging him. Kapoor’s sculpture of a giant hornpipe – Marsyas played a flue in the tale – filled the length and height of the Turbine Hall, and was crafted from dark red PVC “rather like a flayed skin”, he said at the time.

Olafur Eliasson, The Weather Project, 2003

The image of a sun glowing at the top of the Turbine Hall has become one of the most memorable installations in the space’s history. Conceived by Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, The Weather Project was visited by two million people over its six-month duration and replicated a rising sun with a series of lamps and haze machines, complete with a mirror on the hall’s ceiling reflecting the installation’s visitors below. (Such materials and motifs have been enjoyed with renewed enthusiasm in Eliasson’s recent Tate Modern exhibition In Real Life.) “An artwork starts a narrative, but when it comes to deciphering it, I see the public as being co-pilots rather than mere passengers,” Eliasson told AnOther in 2018. “I wouldn’t want to tell them what to think, but rather establish a dialogue – and the quality of a dialogue depends on me just as much as you.”

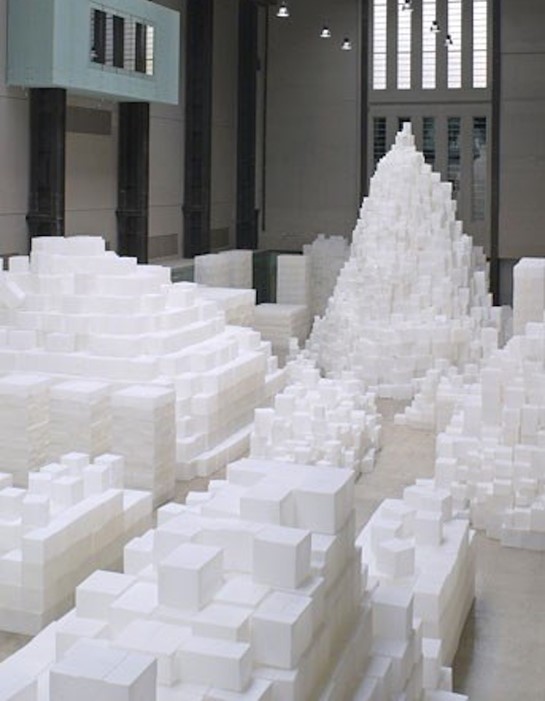

Rachel Whiteread, EMBANKMENT, 2005

In 2005, British artist Rachel Whiteread filled the Turbine Hall with a series of translucent polyethylene boxes, stacked atop one another to create towers and blocks which visitors could walk between. The cubes were casts of cardboard box interiors, since EMBANKMENT’s genesis was the discovery of a worn-out box among Whiteread’s late mother’s belongings. Treating the Turbine Hall like a vast warehouse of sorts – the Turner Prize-winning artist said she had been thinking of the final scenes of Raiders of the Lost Ark at the time – the work addressed ideas of storage, possessions, containers and interior spaces.

Carsten Höller, Test Site, 2006

For Carsten Höller’s Test Site, five swirling tube slides were installed into the Turbine Hall, linking up with each floor of the Tate Modern. “Slides deliver people quickly, safely and elegantly to their destinations, they’re inexpensive to construct and energy-efficient,” the Danish artist, who has incorporated slides into his work time and again over the years – Miuccia Prada even has a Höller slide installed in her office in Milan – told Tate at the time. “They’re also a device for experiencing an emotional state that is a unique condition somewhere between delight and madness. It was described in the 50s by the French writer Roger Caillois as ‘a kind of voluptuous panic upon an otherwise lucid mind’.”

Doris Salcedo, Shibboleth, 2007

A reminder of Colombian artist Doris Salcedo’s 2007 Turbine Hall commission remains in the space to this day, in the form of a faint filled-in scar running the length of the sloping floor. Salcedo used the Turbine Hall itself as her material, rather than simply her space, and cracked its concrete floor. “In breaking open the floor of the museum, Salcedo is exposing a fracture in modernity itself,” Tate Modern described of the powerful chasm conceived by Salcedo, who herself said that the work addressed a long history of racism and colonialism in the modern world.

Ai Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds, 2010

For his 2010 installation Sunflower Seeds, Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei covered the floor with 100 million handmade porcelain sunflower seeds replicas. The seeds were crafted and painted in various workshops in the city of Jingdezhen, famed for its kilns and storied porcelain production. “[In] the times I grew up, it was a common place symbol for The People, the sunflower faces the trajectory of the red sun, so must the masses feel towards their leadership,” Ai Weiwei described at the time. “So much more than a snack, it was the minimal ingredient that constituted the most essential needs and desires.” The huge quantity of porcelain seeds produced for the work, and the necessary intricacy and skill for each one, highlighted ideas of mass production and individuality in a rapidly changing society.

Tacita Dean, FILM, 2011

Tacita Dean’s Turbine Hall commission, simply titled FILM, was projected onto a towering white monolith and watched by viewers in an otherwise blacked-out space (it marked the first film-based commission). At 11 minutes long and completely silent, the 35-mm film work was described by Tate as “a surreal visual poem” comprising images of nature, allusions to artworks and dream-like seqences. Dean’s labour- and time-intensive process – much of the analogue film used for the piece was hand-tinted – highlighted how intricate film work can be, and she hoped to show “film in its purest form”. “There is a bearing of time, for me, that is embedded in actual film – its internal disciplines,” Dean told AnOther of her chosen medium in 2018. “Not to mention how beautiful it is as a visual art form ... it has what I call ‘medium resistance’ since it’s always going to run out in four minutes, or ten minutes.”

Abraham Cruzvillegas, Empty Lot, 2015

A series of triangular wooden plant beds were installed in the Turbine Hall for 2015’s Empty Lot, a work by Mexican artist Abraham Cruzvillegas. Lit and watered for the six-month duration of the show, the beds were filled with earth and soil taken from various London parks, including some in Peckham, Haringey and Westminster. Visitors could witness the changes in the beds throughout the exhibition, though there was nothing specifically planted. “We have little clay bowls as our first layer, then compost, and then the soil that came from the parks, and that’s where something can potentially come from – hidden roots for example,” said Cruzvillegas in 2015. “It’s not that I’m hoping that something will happen, I’m hoping that it’s continuous; the size of the Turbine Hall is so impressive because of the scale, but the real drama is microscopic.”

Kara Walker, Fons Americanus, 2019

The most recent artist to fill the Turbine Hall is Kara Walker, whose piece Fons Americanus was devised as a response to the Victoria Memorial which the New York-based artist saw outside Buckingham Palace while visiting London. Walker created a working fountain, standing at 13 metres tall, which was housed inside Tate Modern until April of this year. The allegorical fountain sees sculptures of figures, animals and objects together forming a subversive take on such historical monuments: Fons Americanus presents metaphors and symbols alluding to the Black Atlantic and history of the slave trade in Europe and beyond. “I’m interested in grand themes and small human frailties, macro and micro,” Walker describes.