Like many artists during lockdown, Marc Quinn has been busy making the most of isolation. In his new series titled Viral Paintings, Quinn reworks stories from his digital news diet into giant paintings which retain the proportion of his iPhone screen. The results powerfully capture both the surreal feeling of experiencing the pandemic through a screen and the liminality of this particularly ritualistic side to his art-making. Quinn has always been a master of making the hidden visible; often drawing from classical sculpture, he brought for instance the socially overlooked discussion of disability into the public arena with his 2005 sculpture Alison Lapper Pregnant on the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square. He exposed the dark world of Abu Ghraib, bringing a surveillance image from this shameful moment of American history into almost supernatural being in his bronze sculpture Mirage. Since his very first iconic self-portrait Self, sculpted from his frozen blood, Quinn as a storyteller has always held us in an animated state of suspended disbelief.

His most recent series of sculptures, 100 Heads (a prequel to the launch of Our Blood), shows Quinn’s amazing ability to create space for others, recharging an often overlooked issue or, in this case, an ignored people, with the power of iconographic symbolism. Casting refugees from conflict zones in places such as Somalia, Syria, Iran, Burundi, Palestine, Turkey, Rwanda and Burma, he creates contemporary versions of Greco-Roman sculpture in raw, untreated concrete – resulting in visceral encounters with the humanity and individuality of refugees that, at first glance, remind you of busts of ancient kings or queens, or religious icons. It was Arthur Symons, the symbolist critic, who was so passionate about seeing beyond the surface into a mixed reality that he described W. B. Yeats’ poetry as where “the visible world is no longer a reality and the invisible world is no longer a dream”, and in many ways that is an apt description of how I feel about much of Quinn’s uncanny ability to trip our senses and in particular the focusing-in of the interplay of the virtual and the physical in this new series of Viral Paintings.

“Art is the memory of the world,” explains Quinn as to why he was inspired to paint every day during the lockdown. Taking his cue from precedents such as Picasso’s painting of Paris during the war, Quinn short-circuited the elaborate process that he undertook for his recent History Painting – where he over-painted onto his pixel-by-pixel photoreal oil paintings of social and political documentary images – in order to re-act and paint his experience of the pandemic unfolding in real time. So he devised a system where once he was struck by a story he would digitally print it, mount it and within a day begin to over-paint, in a state he describes as “not thinking”.

Quinn describes the screen as his “window to the world”. As we know too well the screen, our digital media and our networked social media have been psychologically proven to be responsible for desensitising and dehumanising us as individuals for many years. This feeling of atomisation and dissociation has now been accelerated in this pandemic moment. Quinn’s Viral Paintings, I believe, act to re-sensitise the viewer, bringing us into an empathetic field, a phenomenology of sensing through painting, where a contemporary consciousness meets our unconscious.

“If I’m not in the right zone I can’t do it, it’s very much about letting go of everything, and not thinking,” says Quinn about the trance-like process he puts himself through daily to synthesise the contemporary noise he’s filtering through these performative action paintings. “It’s only afterwards when I look at it that I understand what I’ve done.”

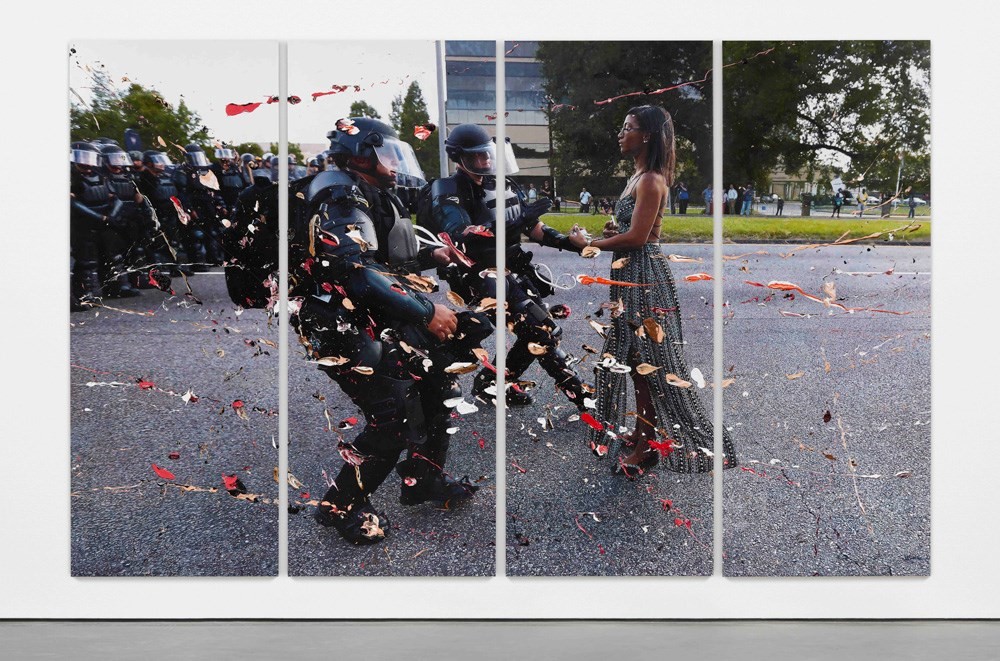

A few days after we first met to talk about the Viral Paintings, Quinn’s practice has taken a shift to focus on the breaking news of the social revolution sparked by the death of George Floyd and international Black Lives Matter and anti-racist protests. He’s caught in a mediated hyperreality, a witness to multiple social revolutions simultaneously unfolding on his screen, immersed in his constant BBC World Service programming which soundtracks his painting sessions. Quinn’s 2017 History Painting of Ieshia Evans protesting the death of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge speaks directly to Quinn’s remarkable gift of creating space for others. This giant painting depicts the grace and dignity of a black woman not only standing up for her rights but evoking, with saintly composure, the decades-overdue reckoning of the debt owed to African-American lives in the face of white oppression. In bearing witness, Quinn also brings us into confrontation with his own privilege, and the history of an art market and system which has always continually reinforced the myth and value of the white European male gaze. He paints the world seen through his screen: witnessing millions marching together, defying lockdowns, to protest – putting their lives at risk to show solidarity for the lives of others. Quinn is one of the few white European male artists who has forcibly worked throughout his entire career to deterritorialise his position, shape-shifting as a decoloniser, re-humaniser and activator of empathy and story using his status and power as an agitator against the status quo to ethically collaborate, fundraise, and support those whose voices have consistently not been allowed by society to have equal status or privilege.

Jefferson Hack: I love looking at this new series of paintings and sensing the layering of information and materials, observing the pain, how the image, the media element, the textual part and so forth pulsate, pushing through and disappearing into the layers of paint.

MQ: Someone posted a comment on my Instagram about these works: “you better plug it in, it looks like it’s melting”. Amazing, right?

JH: Yeah, I love that. That could be the headline.

MQ: Because it’s connected to Self and much of my work. And secondly, it’s this idea that we talked about earlier: the barrier between the virtual and digital is melting. I think that the question of how we negotiate that very border between virtuality and reality is one of the big questions of the 21st century. A lot of my work has that as a subtext to it, or an underlying obsession.

JH: Yes. It’s also very apparent that the paintings are also completely different when you don’t view them on a screen!

MQ: That’s the other thing that’s really interesting for me about art, which is great, but sometimes problematic: that you only really understand a work when you see it in real life. And now people see so much on their screens. But you don’t really understand something is really an artwork until you have a one-on-one. It’s one of the few things you actually can’t download is that experience with a work of art, I think.

JH: Unless you’re a digital artist like say, Cory Arcangel.

MQ: Yeah, but it’s still a fact that a lot of his digitally-originated work becomes a physical artwork too, that is the paradox.

JH: What were the images that made you stop and take a screenshot? What were the conditions you were looking for?

MQ: I think that it’s really about the stories of this particular moment.

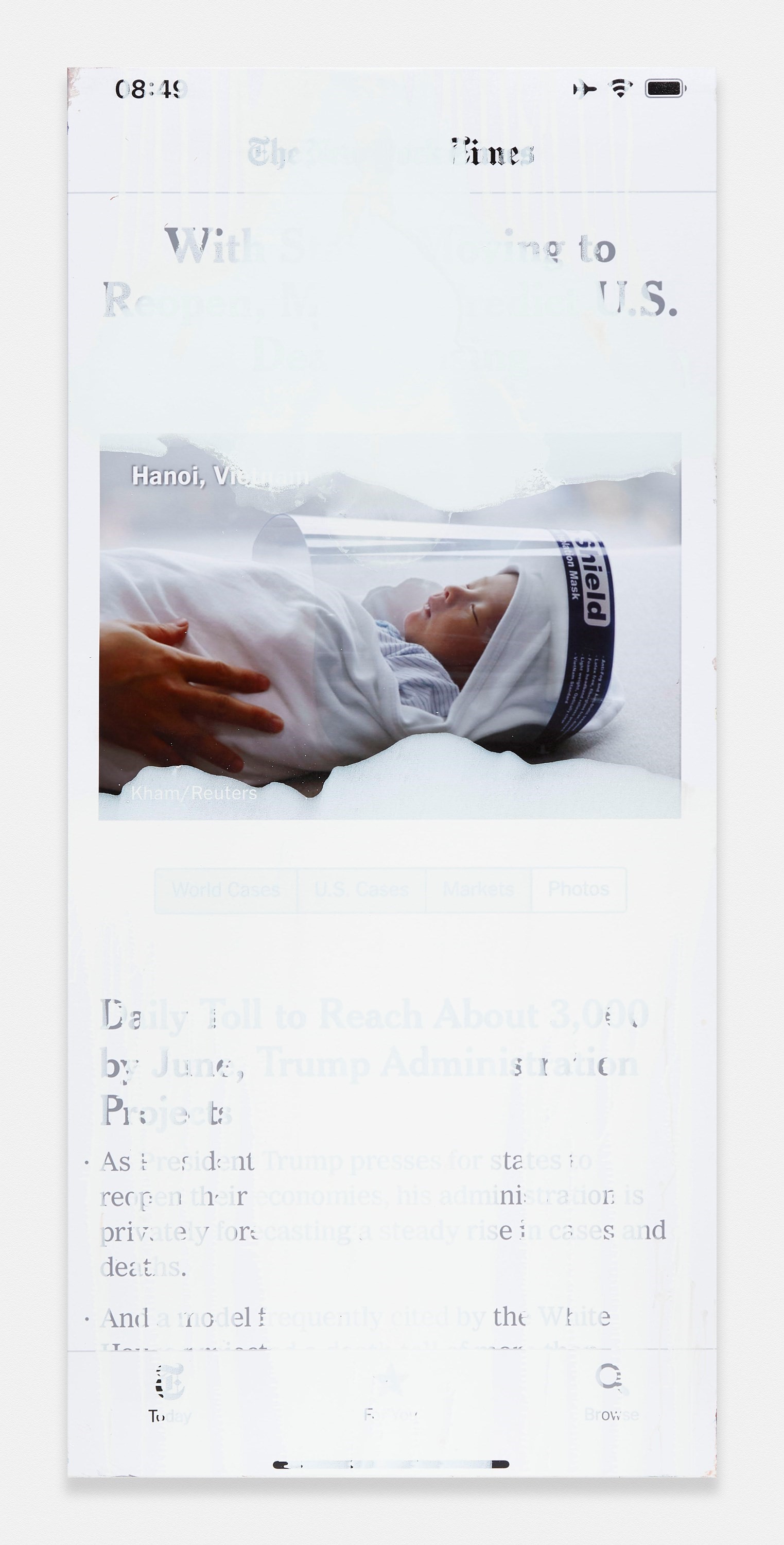

JH: Can we talk through some of the works? I would love to ask you more about the image of Baby Erin.

MQ: I saw a picture of Erin without the mask and she looks very much like a baby, but then with the mask, it changes. Her eyes through the mask now look like adult eyes in some way. She also looks like a deep sea diver or space baby so it’s about the image meaning more than one thing. Look at her, she’s all plugged in on life support it’s just so many different amazing things going on, and then the handmade way that there’s some Elastoplast on top to make the mask fit onto her head.

JH: She represents the ultimate fragility of humanity, doesn’t she? As a metaphor for a species facing extinction we are now maybe all this baby.

MQ: We’re all that baby yeah, and that’s what Self was all about as well, we’re all on a form of life support in a way.

JH: And then let’s talk about this.

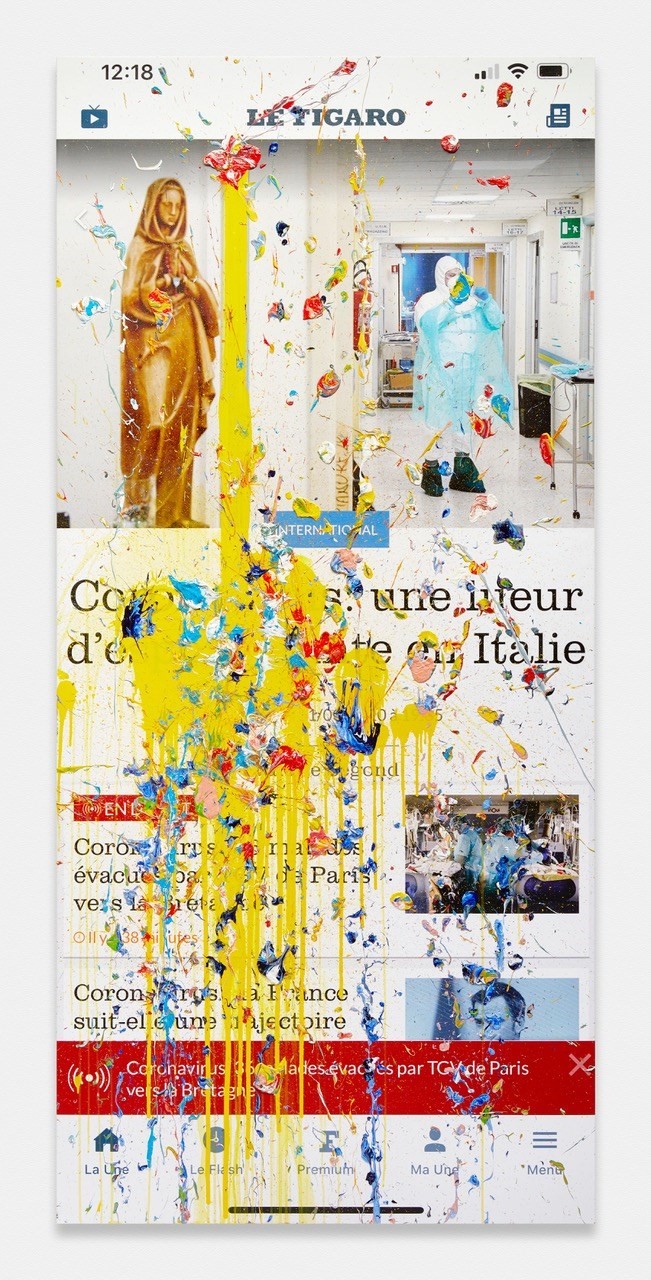

MQ: Yeah, that’s from Le Figaro. An image from the San Filippo Neri hospital in Rome.

JH: It looks very apocalyptic.

MQ: It is very apocalyptic. And yet it also feels almost like a religious painting because you’ve got the Virgin Mary there. And the nurse is wearing protective gear. So, it’s also about how religion in these kinds of situations can no longer provide an answer. You know, what’s the answer that it can give?

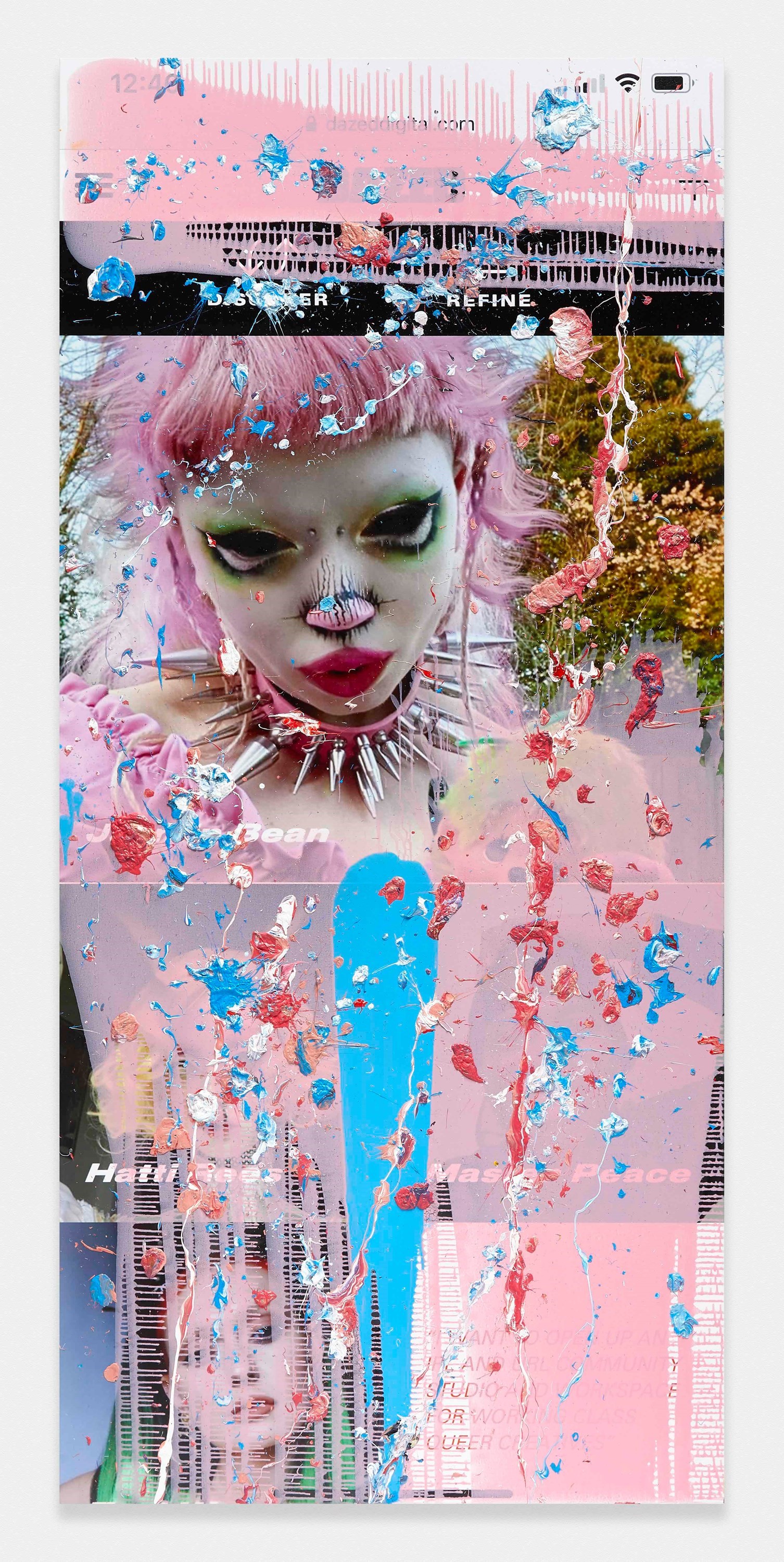

JH: Let’s talk about the painting which is reworked from a Dazed Digital story.

MQ: Yeah, that’s Jazmin Bean from the Dazed 100.

JH: What made you gravitate towards painting them?

MQ: Because I think they’re living in this world between realities. Their look is also between a sculpture and a living person. They’ve created themself and I’m reflecting on the fact that there are still kids reinventing the world. Not everything stops. Love continues, young people reinvent the world and the world continues. All these things are happening in parallel.

JH: The one of Britney Spears represents a different technique because it doesn’t have the energetic splattering of paint.

MQ: No, it’s almost a kind of a Madonna of the series in a way, or a Marilyn, there’s something archetypal about it. The pink screen that covers the image makes her appear between visibility and invisibility.

JH: When I looked at it, it made me think of the kind of the impotence of celebrity in this time. They’re not as interesting or relevant in this moment.

MQ: Yeah.

JH: And I think this is almost a kind of way of acknowledging that.

MQ: But you know the story is of her burning down her gym as well, so it’s this idea of a world on fire. Destruction. And also then she’s doing a workout thing after that. So there’s a sense of renewal after that destruction.

JH: “Quarantine Queen Britney Spears burned down her gym and shared a workout routine.” There you go. Yeah. Culture is in a spin cycle that is just accelerating.

MQ: It’s that fast you know, you burn it down, it comes back again.

JH: For me that story represents an inherent illusion in the mind of many that you know, things could just come back that quickly; the same old shit recycled.

MQ: If you look at the actual photograph, it’s not that interesting. It’s only once it has this layer of paint on top of it that it becomes somehow rather ethereal and beautiful.

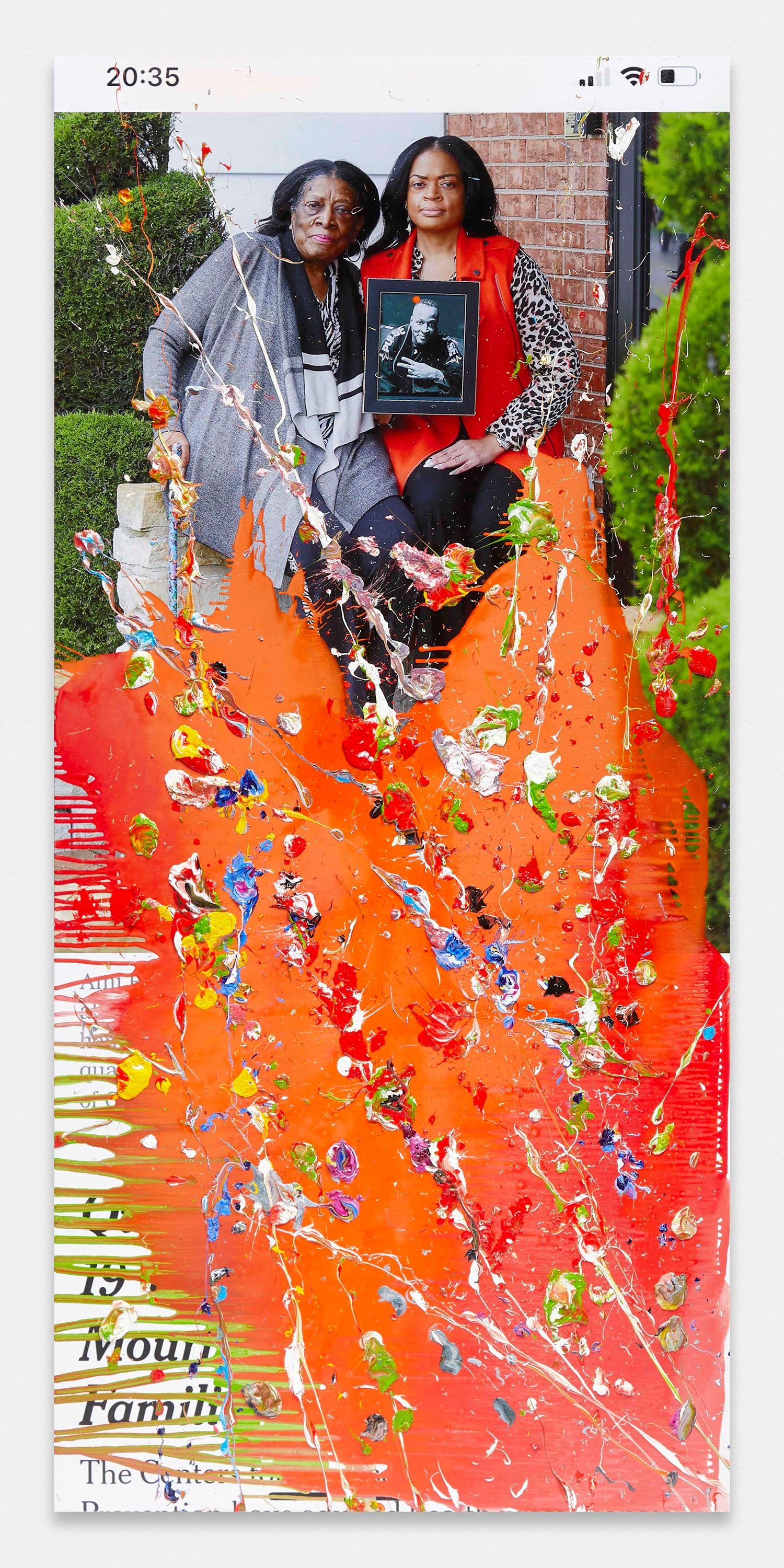

JH: Yeah because what I love is that the actual media story is just a base layer, but it’s not the story of the painting. Like the portrait of the American family who have lost their son.

MQ: Yes, this painting is of the Relf family, it’s about the racial bias of Covid-19. People who are less advantaged have less chance.

JH: Yeah you had said something to me about feeling like you were placing flowers onto the painting with the way you placed the paint onto the image.

MQ: Yeah. And I felt like Ami Relf’s coat has come down, almost like the cloak of the Virgin Mary covering the world. And so that orange comes from her coat and descends. That’s a very moving one.

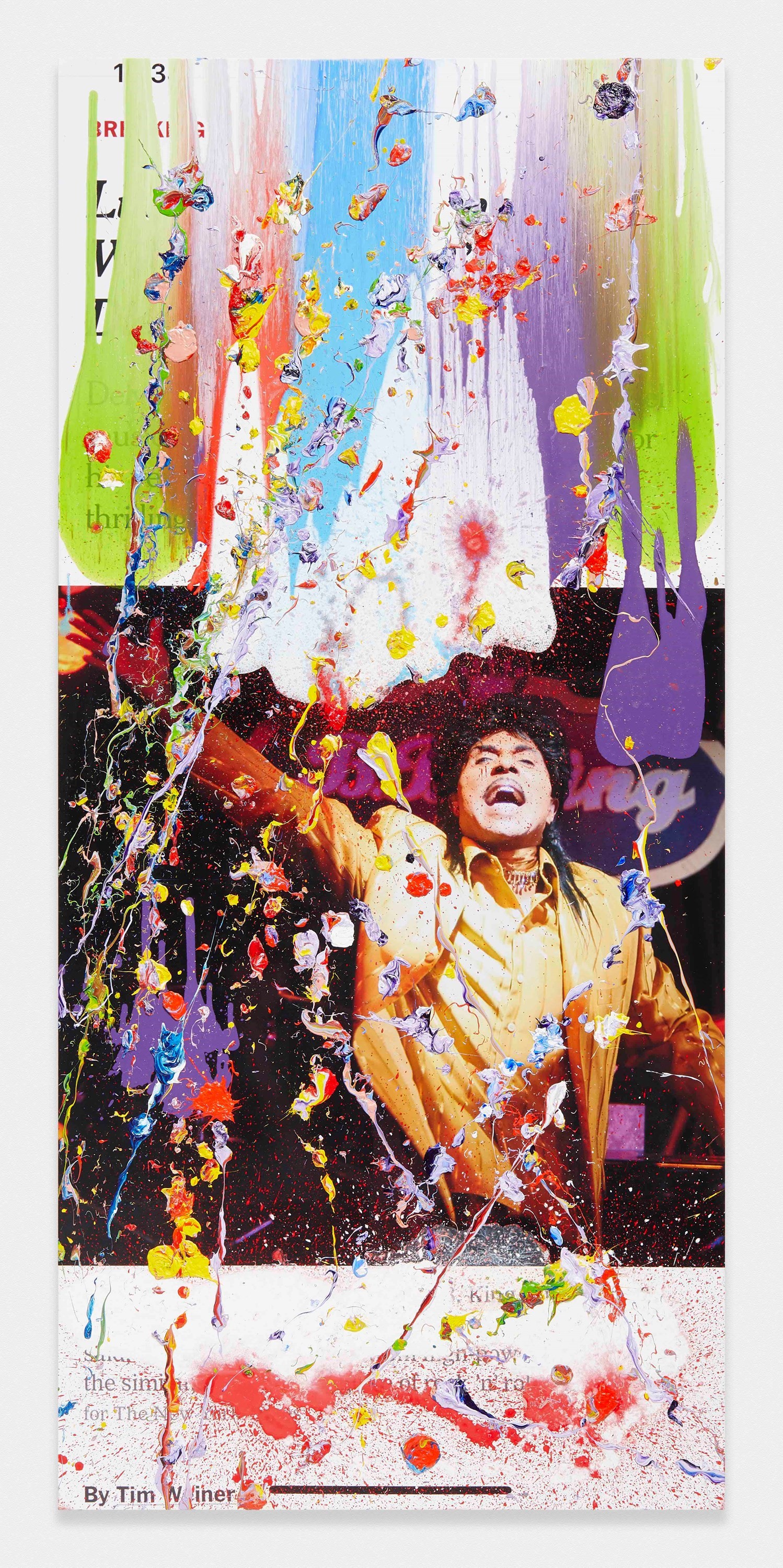

JH: Why did you paint Little Richard?

MQ: Because he was a huge important cultural figure and we can’t forget other things that have happened. Without Little Richard you don’t have rock and roll and so it seemed to me that his passing is a time to remember him as a great artist as well. So when his story came up it just seemed like one I definitely wanted to do.

MQ: This is my friend Hassan Akkad. He’s a refugee from Syria, we met and began working on my project Our Blood together. Hassan won a BAFTA for Exodus – a documentary he made on his phone about his harrowing journey from Syria, where he was jailed and tortured, to Europe. I recently made a sculpture of him for 100 Heads. Then I saw in this article that he was volunteering to be a front-line worker as a cleaner at his local hospital in London. He’s an incredibly inspirational person.

MQ: This shows us the beauty of creation and an image of hope, that there is something to come after this as we are witness a new-born child. People may be dying, but there’s also children being born every day.

JH: The cycle of life. You’re looking for miracles.

MQ: Yeah, it’s a miracle: the beauty and drama of the miracle.

MQ: This is an image of the Paterson First Responders in New Jersey. What really struck me about this image was the structure of it. The person holding up the lamp to decontaminate the back of the ambulance reminds me of the Statue of Liberty or the William Holman Hunt painting The Light of the World. There’s so much going on in here and I really see several likenesses to Old Master imagery in it, while the paint on top feels like mini galaxies of potential. Each splash of paint is matter in the real world and as it passes through the boundary of the phone screen, it dematerialises into image, passing through the littoral zone between the virtual and the real.

MQ: This image is interesting as it shows the continuing disparity between the West and the rest of the world. You can almost imagine these two scenes happening at the same time but it’s the pagination playing with your imagination. You’re seeing a girl with a flag celebrating VE Day in Chester, and below, health workers spraying disinfectant on a girl in Kathmandu.

JH: I’m interested for us to talk about some of the technical aspects of how you achieve this effect.

MQ: So, I mean, there’s multiple ways of putting paint on these – one is by pouring it, in layers, so layering it like a Morris Louis painting ... And then I have all the paints, on big palettes. I sometimes use big brushes on the still wet paint. And I get my palette knife and take a little bit of each paint, so there this is a mixture on my knife. Then, when I throw it onto the canvas on the floor, when the paint hits the canvas, it fragments and it creates the mixtures and patterns. And when you go really close to one, you look at any one of them, there is the whole chaos of the whole world in there. And if you actually were able to dive into the middle of it, that chaos is like fractal; it just continues. Paint in its abstract form holds all the possibility of every painting ever painted, yet it is also complete chaos.

JH: It’s very psychedelic.

MQ: Yeah. It is psychedelic, it’s almost like a trip.

JH: Within each paint splat is the beginning of a universe, a big bang.

MQ: Like William Blake’s line “hold infinity in the palm of your hand”.

JH: There’s obviously a lot of consideration in terms of colour, precision and pacing of paint.

MQ: Definitely, you can fuck it up very easily.

10 per cent of proceeds from the Viral Paintings sales will go to WHO and NHS. 10 per cent of proceeds from Viral Paintings relating to the Black Lives Matter movement will be donated to Black Lives Matter.