Back in 1988, photographer and journalist Dave Swindells kept hearing how the island of Ibiza, “a strip of rocky soil in the Med”, was where it was at. As Time Out’s Nightlife Editor he was “fortunate to be in the right place at the right time when the tsunami of excitement generated by Balearic Beats, Acid House and ecstasy, broke over London, as I was writing about it every week”. He was also one of a handful of photographers trusted to document clubs like Danny Rampling’s Shoom, and Paul Oakenfold’s The Future.

Swindells got into photography while studying in Sheffield and first took nightlife photos at clubs run by his promoter and musician brother, Steve, in London, then networking the alternative and underground scene as his work began to get published. Of Acid House he says; “It was immediately apparent to me that this was going to be massive; it had new music, new fashion and a ‘new’ drug [ecstasy] that gave it potentially enormous appeal”.

1988 was dubbed the ‘Second Summer of Love’, thereafter the momentum of the scene took even Swindells by surprise when a rave, the Sunrise Midsummer Party – drew 11,000 ravers to an airfield in Buckinghamshire in summer 1989. At the time, Ibiza wasn’t anything like as well-known as it is now, but Swindells’ contacts Rampling and Oakenfold, a Spanish clubber he’d photographed, and work by photographer Derek Ridgers all referenced the island. It was clearly his destination, despite the fact that at the time he “was just earning enough to pay the rent and buy camera equipment and film,” whereas “Ibiza was a fantasy island where popstars like Wham cavorted in their Club Tropicana video!”

Along with writer Alix Sharkey, whose blistering observational essay is reproduced in full in the book – Swindells finally got the opportunity to travel to Ibiza on assignment for 20/20 magazine in June 1989. The shots from the seven or eight rolls of film he’d packed would eventually result in IBIZA ’89, which is published by IDEA.

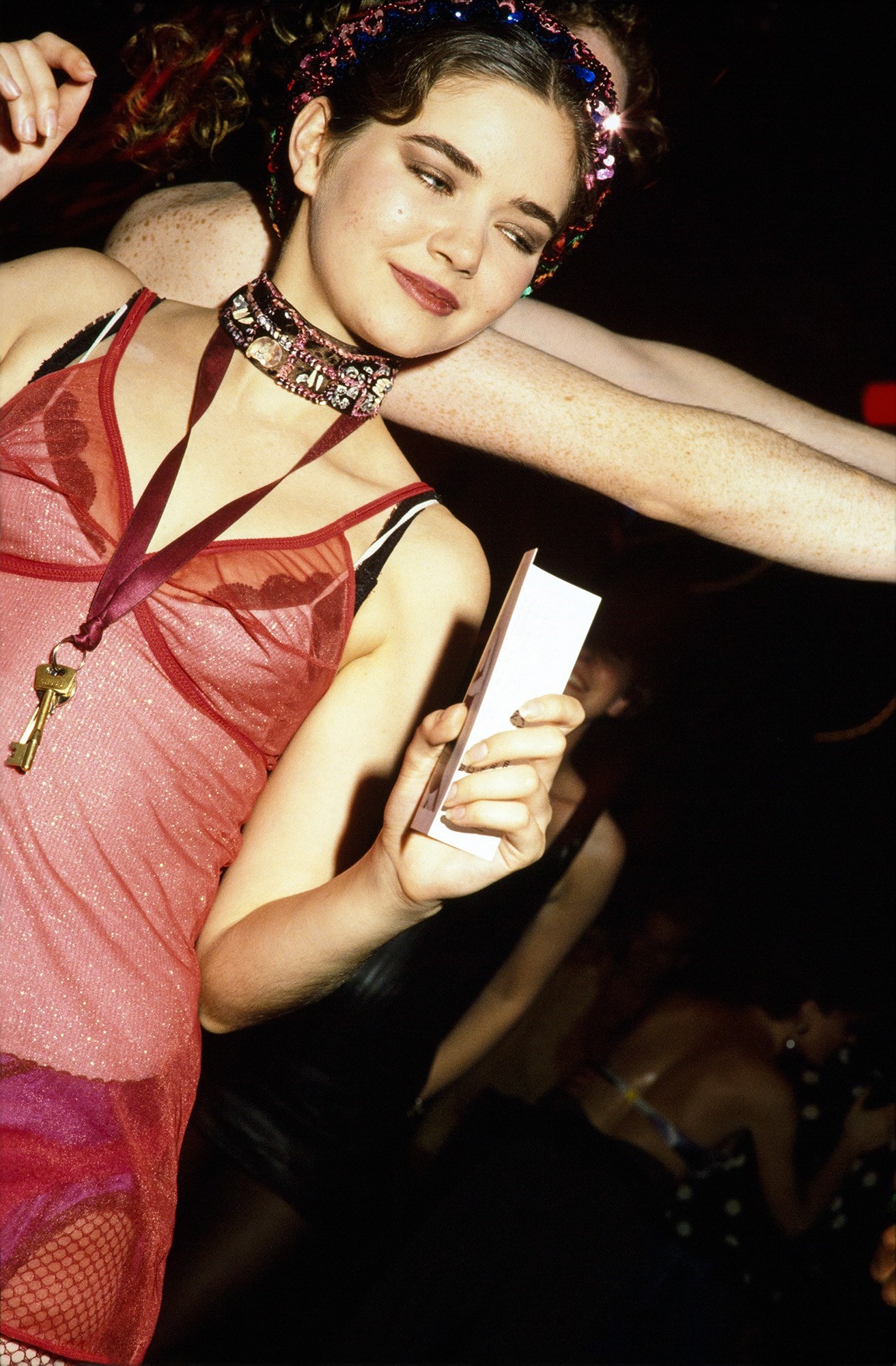

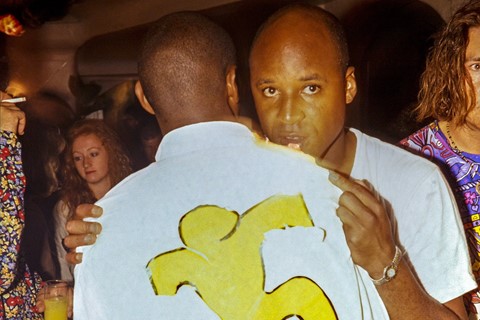

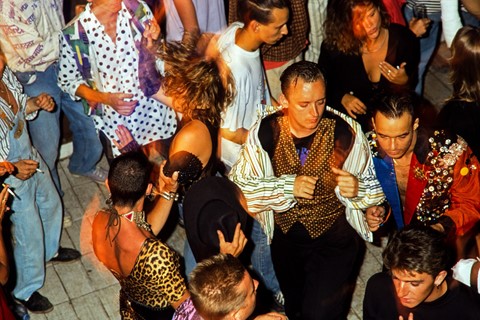

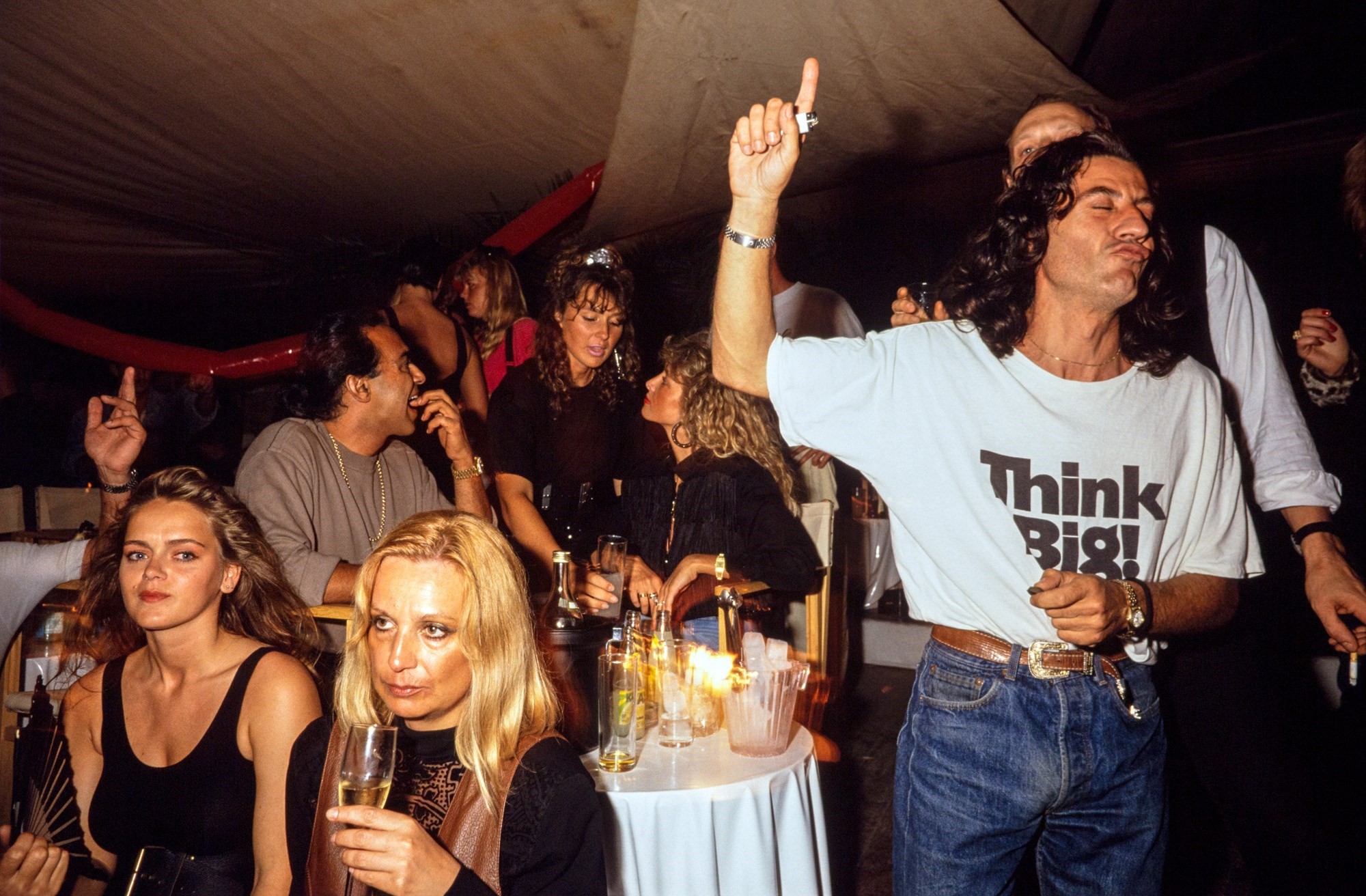

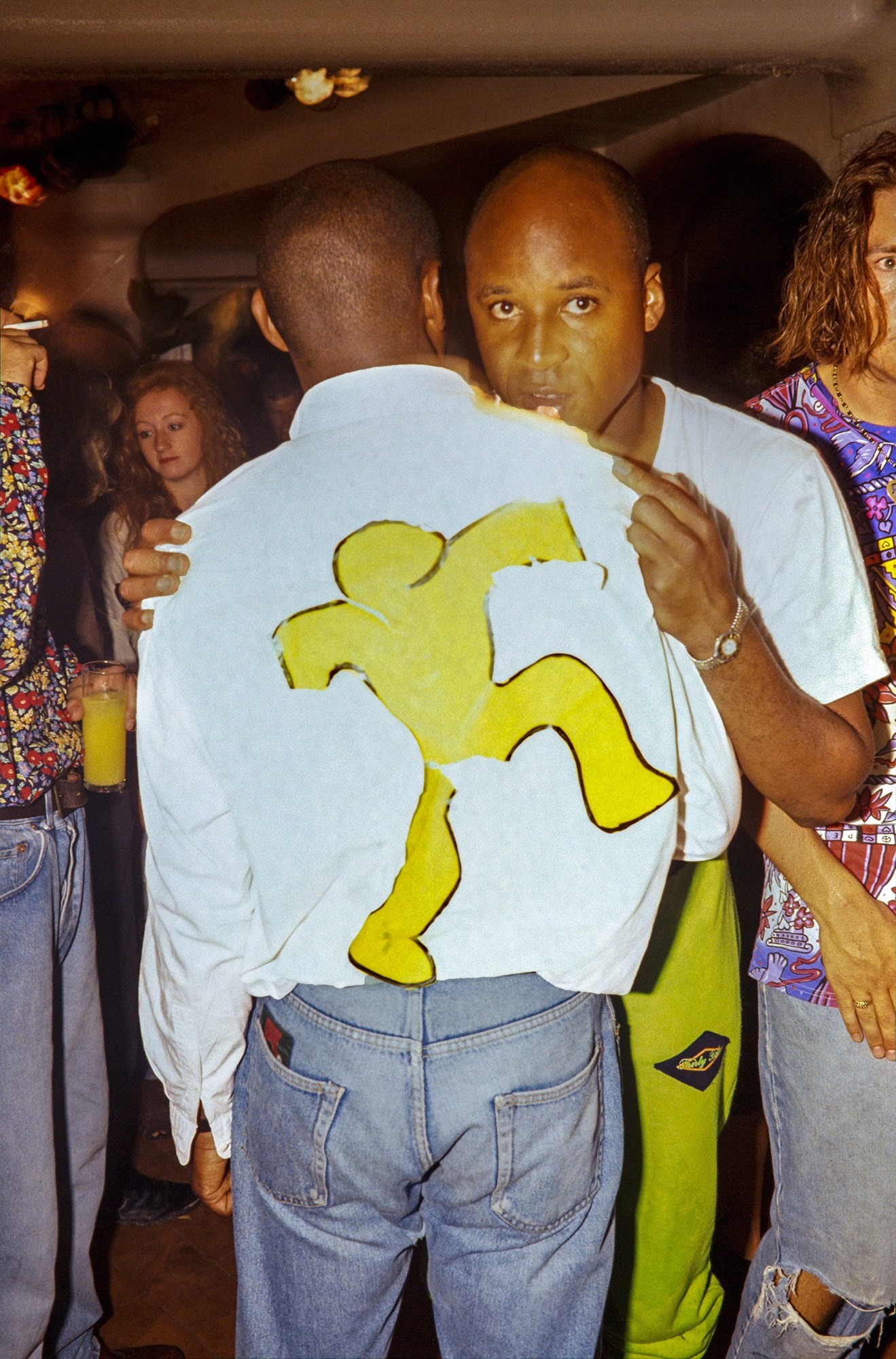

The lush, reportage images capture a microcosm of nightlife in a pastel colour palette. Swindells remembers “carrying a mini-tripod with me so that I could shoot longer exposures to capture the scale of venues”. Many of the book’s dancefloor shots were taken in Amnesia after the sun had come up – a bonus for a photographer more used to shooting in cramped Soho basements. Club goers included “very smart, suavely-dressed people around the bars in Amnesia”, as well as “grandmas at Pacha, and middle-aged characters who could have been princes or CEOs dancing alongside kids in rubber fetish-wear or queens in furry shorts”. A quote from a British clubber whose portrait is featured (in a pink T-shirt reflected in a mirrored pyramid) described partying with an Italian princess, whose friends carried water pistols filled with liquid ecstasy, as “the best night of my life”.

There’s a sense of innocence and magical possibility, that something new was being discovered, before the hype of Ibiza Uncovered or the era of corporate superclubs. As Swindells writes in the book’s introduction, “It was easy to believe that almost anything was possible in Ibiza in 1989; that many of the big clubs put MDMA powder into their cocktails; that the music could jump across genres ... that it didn’t really matter about your age, sexual preference or how much money you had.” Even the coolest clubs would let a few party-goers in for free.

The book’s resonance with 2020 goes much further than the eerily similar fashions of the time; mesh slip dresses, high-waisted belted jeans with crop tops, bumbags and long-sleeved printed T-shirts all easy to imagine changing hands on Depop today – to a collective longing for the dancefloor, while their doors are closed during the pandemic.

It’s an appeal to protect these spaces, too. “Nightclubs, live music and arts venues need support to survive the pandemic,” says Swindells. “Effectively a vaccine will be necessary before clubs and festivals can function again – it’s terribly tough on the individuals who make these events happen.” The photographer defends the business he’s made his career in, saying, “it’s astonishing how wilfully clueless the government appear about how many people work in these industries and how much money they generate for the UK.”

Just as importantly, the book is a form of escapism. “Do people need reminding that another life is possible? Probably not, but this book is an antidote to locked-down Britain,” Swindells says. It provides a dose of “searing Mediterranean sunlight onto hot summer nights in spectacular locations – and the clubbers who really made the most of the experience”.

IBIZA ’89 is published by IDEA.