Ibrahim Ahmed’s new solo exhibition includes the Giza-born artist’s photo-collage series about his self-release from limits of male performativity

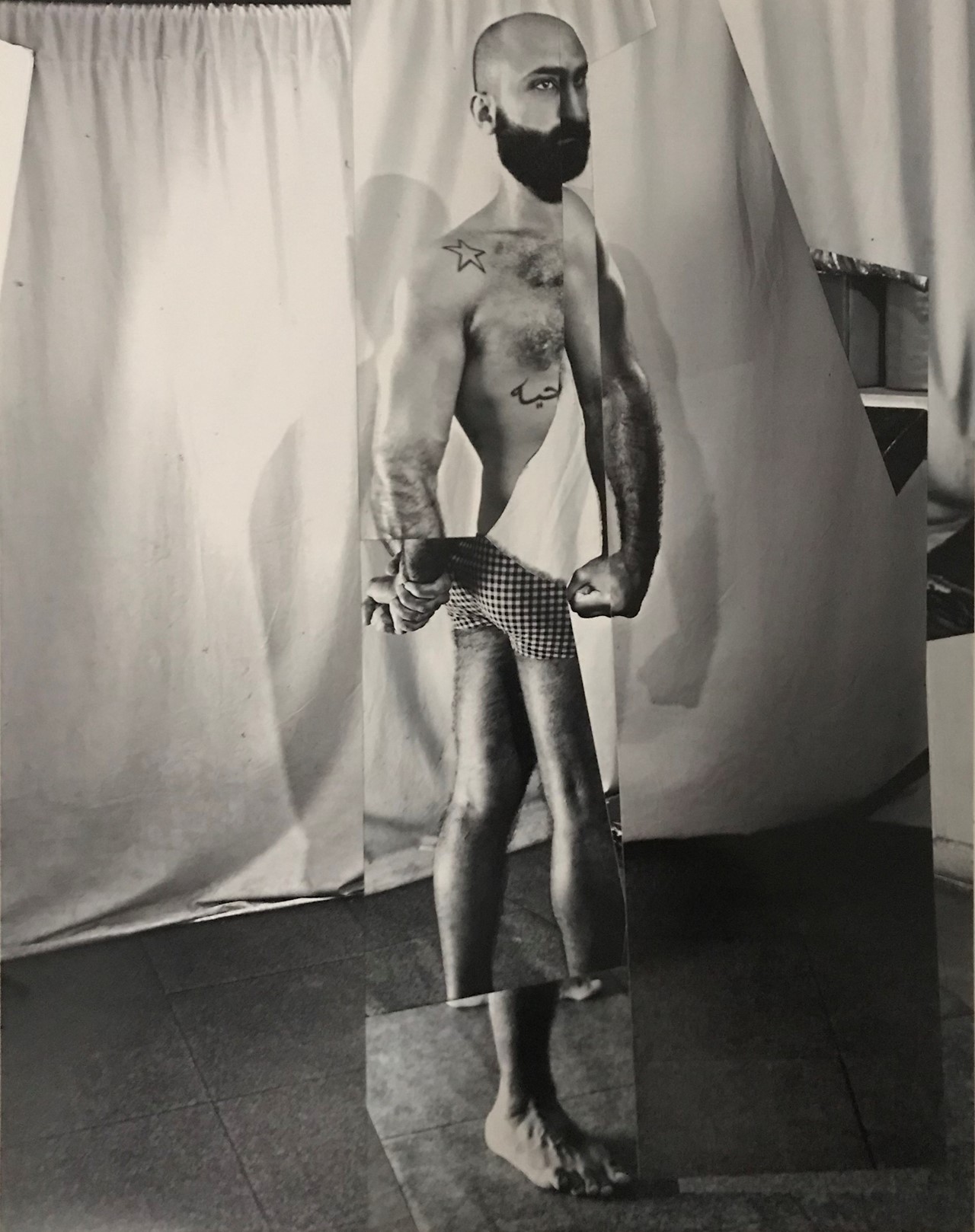

Last year’s forced isolation prompted Giza-based artist Ibrahim Ahmed to revisit his 2018 photo-collage series, Burn What Needs To Be Burned. Rendered in black and white, the images consist of cut-outs of photographs of the artist’s own body, in deconstructed forms that play with limbs’ geometric potential: an arm becomes a leg, Ahmed’s face is carved out to open room for his back. Meanwhile the backdrop alternates between a local photography studio with a white cloth draped over the wall and the artist’s own studio where he dabbles with a piece of concrete and ropes. His tedious struggle with the concrete, in which he lifts, throws and repicks the weighty block, recalls that of mythological figure Sisypheus’ with the mountain rock. The unending battle reflects the entrapment of masculinity which Ahmed long found himself contained by. Born in Kuwait, the artist has lived between Bahrain, Egypt and the US, shifting between cultures while his Arab male identity was molded into different political entities by different societies.

The limited resources and inevitable contemplation during the pandemic led to You Can’t Recognize What You Don’t Know (2020-21), which includes reinterpreted images from the former series. The artist returned to his own body both as a physical force and a political site through deconstructing and then reconstructing photographs. Each attempt to move bits by hand revealed another meaning. In the images, Ahmed appears in just a pair of briefs that he purchased in his neighbourhood. The intentionally tacky pattern reads “love” all over the garment. The tension between him and the concrete is evident, perhaps signaling the distress of an unpredictable global emergency. The artist’s body is fragmented and more violent compared to the former series, while his forceful gestures are still evident.

The photographs are currently on view in It Will Always Come Back to You, Ahmed’s first solo exhibition in the US, which recently opened at Institute for Contemporary Art at the Virginia Commonwealth University. Besides sculptural textiles, a video and an installation of sails inside the museum’s decorative outdoor pool, the artist’s photo-collages occupy the gallery walls with images of his deconstructed and rebuilt body. Cairo and London-based Tintera Gallery will present a solo exhibition of Ahmed’s collages in October in Egypt.

Here, Ahmed walks us through his journey of facing the failings of masculinity and his path to ease through photography.

“In 2018, I found myself in a place of harsh self-critique due to exhaustion, both from the burden of masculinity and the fear of facing myself, which I eventually did. I needed that moment of ease and deconstruction to create something new. My Burn What Needs To Be Burned series came out of the process of the most radical act I could ever think of at the time: to look at myself in the mirror. When I returned to the photographs last year, I just had to make work without worrying about where or when I could show them.

“The work is not about theory, but instead purely about my lived experience, which at the time felt as if I didn’t have the language around. Reading Wilson Chacko Jacob’s book Working Out Egypt: Effendi Masculinity and Subject Formation in Colonial Modernity 1870-1940 was an eye-opening moment. The British Empire’s modernisation project over colonised Egypt targeted the so-called stereotype of lazy and effeminate Egyptian man. The ‘effendi’ type of masculinity was formed by pulling men out of their social habitats and having productivity in the workforce. This also meant the erasure of women and non-binary people. Khawal, for example, was a male belly dancer who wore clothes associated with both men and women. These dancers were eradicated during colonisation and the word slowly evolved to mean gay man in pejorative way. My dad’s generation, which just came out of the liberation in 1940, is the product of this constructed and dominant masculinity in the society today.

“I knew from the start I had to use my own body to photograph. Besides the series’ personal aspect, I had to be careful against orientalisation of the north African Arab male body, so I avoided bringing in another model. When I first showed the works in Rome at Sarah Zanin Gallery, they were immediately considered homoerotic. The images are about fragility and virility, which is evident in my cheap polyester underwear.

“The first series, as well as the ensuing You Can’t Recognize What You Don’t Know and Some Parts Seem Forgotten, which includes cut-out photographs of my father from the 1970s and 80s, came from a search to place my body in societies. The plural here refers to my transient positioning between Kuwait where I was born, Bahrain and the US where I was raised, and Egypt where I currently reside. Misplacing my nationality is quite common wherever I show my work.

“The answer to why I choose to live in Egypt when I have the option to live in the US is about what I can negotiate and what I cannot. I was familiar with the realities of Egypt when I moved back there, but those are situations I am OK to deal with. The tokenisation and existing as a monolithic idea of a religion in the US is something I got too tired of and chose not to face any longer.

“I photographed myself at my own studio in Giza and at another photography studio nearby in 2018. The photography studio had an archive of 20th century studio photography, most of which included men in different attires and performances. My Egyptian gallery Tintera’s archive of studio photography preserved from the 19th and 20th centuries has been helpful and inspirational in observing dress codes and performativity among men. My postures allude to Greco-Roman male sculptures but I don’t intend to make a clear homage to western art. Gestures are about the architecture of the body and reconstruction. I fight with a piece of concrete that I found on the street. It’s common to see these slabs in Egypt and the rest of the region where they have an everyday use of securing parking spaces. I am not hiding the props around the studio either and let them creep into the frame.

“The mask which sits in the middle of the photographs at ICA serves as a core element. It’s a found part of a Mercedes car. I use collected objects in my textile works, as well. Here, the mask, which is partially a foreign car, refers to possessive masculinity. The second we put on a mask, we are taken over by a need to perform to a point that sometimes we don’t realise it.”

Ibrahim Ahmed: It Will Always Come Back to You is at ICA at VCU, 601 W. Broad Street, Richmond, Virginia, USA, until 7 November 2021.