This story is taken from the Document section of the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Legacy

“Legacy is a big word for an artist. Part inheritance and part archive. Especially for a performance artist. How can I possibly convey the mindset, the values, the process behind good performance art? Performance art is experiential. It is in the ‘here’ and the ‘now’. You have to be present. You need to be present.

“How do we reanimate the documented but un-documentable? How do we share something that existed – but is no more? How do you archive emotions?

“Perhaps we cannot. At least not in the classic sense. What we cannot do on paper, film or any known modality, or any that will be invented in the future, we can do through other people. Artists and participants. Through their hearts, minds and memory.

“Performance is participatory. There is no performance without people.

“This is the reason I founded MAI (Marina Abramović Institute). To provide a platform for other artists to share their work. And for participants an opportunity to be part of that sharing.

“To communicate and disseminate the artistic values, the mindset and the process of true performance art.

“MAI explores, supports and presents performance in every way and every form possible and creates public and participatory experiences.

“MAI strives to be in difficult places at times of fragility. We have been in the outskirts of São Paulo in Brazil, in Ukraine during the invasion of Crimea, in Athens during the financial crisis and in Istanbul during the most polarised elections of the past 30 years. We want to capture art where it is most important at the moment it is conceived.

“Perpetual movement is at the heart of our practice. We are nomads of ephemerality.

“MAI is committed to inclusive artistic practices. We strive for an art made of transparency, vulnerability and truth.

“Being an artist is a constant search for process. And we have opened our process to prepare artists for performance to everybody. That said, even the distinction might be obsolete or even redundant.”

– Marina Abramović

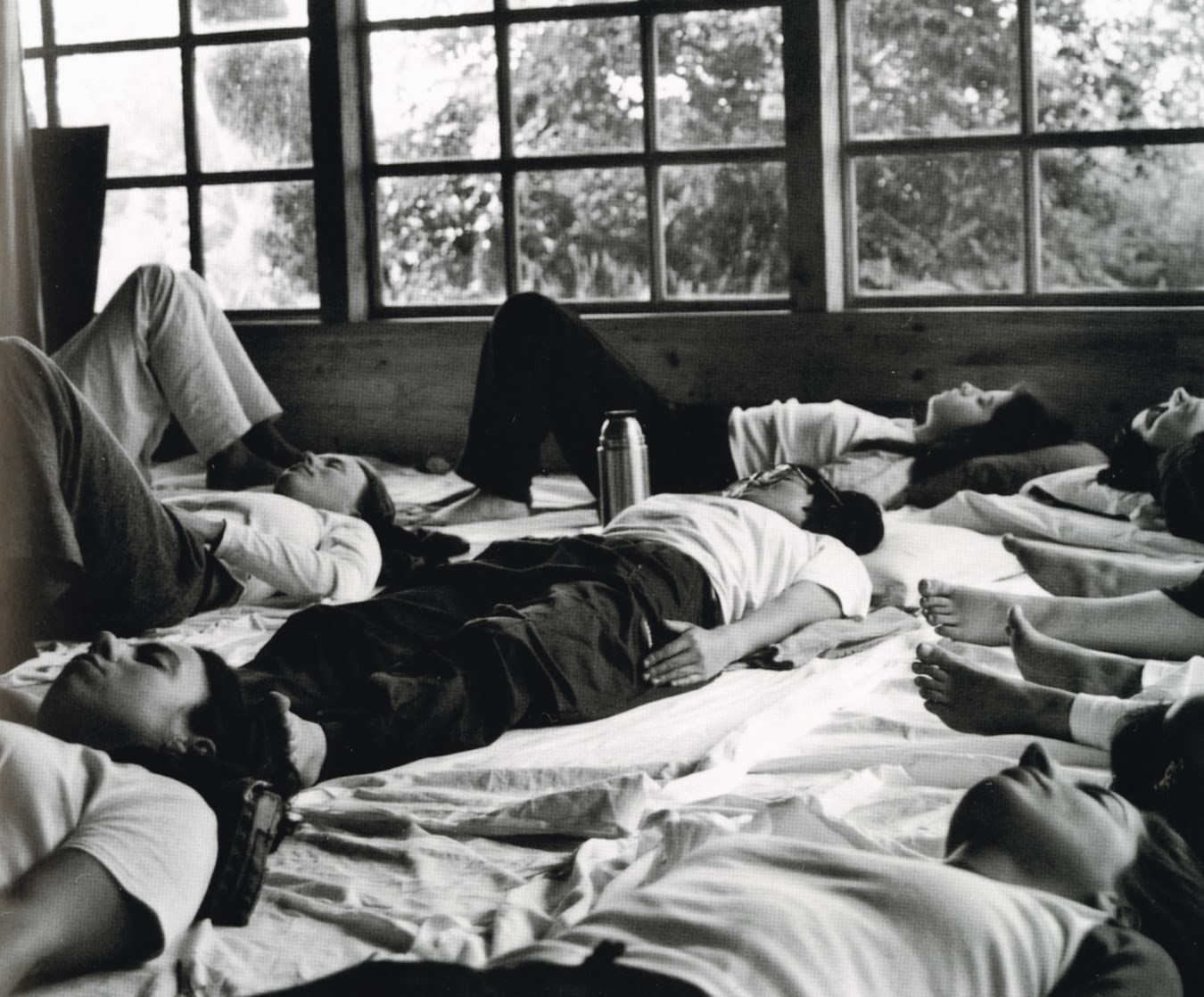

Cleaning the House

The Cleaning the House workshop was developed by Marina Abramović over more than four decades of teaching. Its title refers to Abramović’s metaphor of the body as our only ‘house’.

Hosted by MAI, and held all over the world, the workshop challenges the body’s physical and mental limits, forcing it to respond to and reconnect with its environment. This training is a method towards achieving heightened consciousness and a deepened understanding of oneself.

During the workshop, participants are asked to refrain from eating and speaking, to bring body and mind to a quiet, calm state. They are led through a series of long-durational exercises to improve individual focus, stamina and concentration. The workshop offers the opportunity to be in nature, away from distractions, and to participate in a carefully timed set of exercises and activities to improve both our determination and our ability to generate new ideas.

This type of preparation provides the proper process and setting for a complete internal reset, essential not only for performers as they approach their work, but also for other practitioners and professionals across all disciplines.

Maria Stamenković Herranz

Maria Stamenković Herranz studied at the Vaganova Ballet School in Novi Sad, in the former Yugoslavia, and later graduated from the Rambert School of Ballet and Contemporary Dance in London and Maggie Flanigan Studio in New York. An interdisciplinary performance artist, Herranz strives to illuminate the hidden structures we create to feel safe, but that in turn also limit us. Her work continually seeks to lay those structures bare, “to desolate them and forge a path of return”, she says, “beyond nation states and borders, back to the truest sense of home – the body itself ”. In her 24-day blindfolded performance This Mortal House, the artist constructed a labyrinth inside Istanbul’s Sakıp Sabancı Museum. For eight hours a day, six days a week, she built the structure brick by brick from the inside out, using the mythological blueprint of the labyrinth that the craftsman Daedalus built in Knossos, Crete – designed to imprison the Minotaur, the maze was so elaborate that Daedalus himself had difficulty escaping it. In the following piece Herranz describes the revelatory experience of performing This Mortal House last year in Istanbul.

This Mortal House

Akış/Flux, Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul

11 February – 8 March 2020

The performing artist legacy for me

feels like,

the recipe of a good bowl of

minestrone

that’s been passed on.

In the pot of minestrone,

there is a variety of ingredients

that coexist together.

The minestrone can be a shared

experience

and an individual one.

The minestrone is passed on through

generations.

It’s an experience

that is specifically prepared

so we

eat it

share it

digest it

and have the moment

to let it disappear.

But we have a recipe,

written on a piece of paper,

that is passed on from generation to

generation.

Without this piece of paper

we wouldn’t be able to sometimes

taste some of the best dishes

that give us not only an ultimate

experience of some sort

but as well enable us to have

conversations of history,

speak of cultural heritages

and have an understanding

and awareness of the time passing,

without mentioning

the invaluable necessity

of transformation

that is a basic human need.

Having come from the theatre

dance

to performance art,

in each form

I question how,

as a performing artist,

moving through these various forms,

I can pass the legacy of the

performing work.

I discovered there are two key

ingredients:

presence

and

creating a trace.

Being present creates impact.

Impact creates echo.

Echo creates a trace.

And if you create a good cauldron for

the trace to sit in

then you have a recipe

that can be passed on

and you create a legacy.

Leaving traces

is inevitable as human beings

and I strongly believe

that our stories

our heritage

our individual experiences

impact our shared experiences,

and thus allow for the performing

artist

to be part of an important aspect

through the practice of ephemeral

art,

and be a valuable asset

to the development of our society.

Given the times we live in,

shared experiences

have taken on

new dimensions.

Today

there is something

in moving forward,

a heightened sensibility,

a vital necessity,

that one

not only acts

on behalf

of oneself,

but on behalf

of others

and for those

that come

after us.

Years ago,

in 2004,

when I met Marina Abramović,

I was instantly awed

by her sincere desire

to know about my work.

She was genuinely curious

about how my mix of

the west and east

harmonised with one another.

Since I grew up

with a Spanish mother

and a Serbian father,

I recognised

that the similarities

with those of my father

in fact

were quite uncanny.

My father was born the same year

as Marina Abramović.

They grew up in the same system,

have the same humour.

When I saw Marina’s work for the

first time

my blood moved,

it was like being home.

I recognised the energy,

I recognised how my culture

channels pain,

depth

and humour.

But above all

I recognised

the resilience,

the wild warrior strength,

with which our culture had to survive

from century to century.

When I was invited to collaborate

with Marina

as a performer,

and later commissioned as a

performance artist by MAI,

I felt like destiny was doing its thing.

We work and perceive energy very

similarly.

We tend to put our gazes in kindred

directions.

We are moved by a deep longing to

connect;

to be transformed in unison,

but so as to fight

to keep our own fires afloat,

even when the winds are against us.

I feel that we both strongly believe

how positively the performing

arts

can change individuals at a deep

and cellular level.

We both set up protocols

for those shifts to occur.

From the moment I saw her work

I knew instantly it was inevitable

that I was going to be part of her

legacy.

For we both speak the same

language.

In 2020

I was asked

to create a new long-durational

performance

for the

Sakıp Sabancı Museum in Istanbul.

I was

at a very particular moment

in my life.

With This Mortal House,

I feel I reached a shift in my work.

With this performance piece

the many years of life’s experiences

I gathered

came to a standstill.

My focus

and the dedication of my performing

career

came to an end.

A birth

to a new beginning.

Somehow

unconsciously

I felt it before I began.

I was electrified

leading up to the start.

The protocol I created

came from a deeper

place than I could explain in words.

As Dostoevsky points out in the book

The Adolescent:

“There is immeasurably more left

inside

than what comes out in words.”

It felt like falling off a cliff

right from the start.

Having no idea

how I’d pull the concept through

was in fact

the beginning of the transformation.

To allow the unknown

to lead me

was the path I had taken.

All I understood

was

I had to let my body

be the vessel

and

lead me through

the darkness.

After years of classical training

I’ve travelled a long road

of letting go.

This allowed

for the work

to come to fruition

right in front of

my blindness.

The audience

saw

before I could.

Somehow

I understand now,

I turned the mirror inwardly

and let the visitors

reflect their own image.

When I think of it now,

I feel such purity

lending such trust

to people.

Somehow

it’s the connection

I still long for today.

I had such a deep desire

to disappear

as a performance artist.

I had

this burning desire

for the protocol

to grow into its own animal,

be its own entity,

and let people

look at themselves

through me

and not at me.

I remember

somehow

it gave me such an

enormous feeling of freedom.

Even now

I know it’s the

hardest piece

I have ever made.

I still carry

the physical traces

in my eyes

to this date.

At times I am afraid

there is something wrong with them.

But it teaches me too

that the body decays

by nature

and that acceptance

is part of the process.

This has been

a transformational experience,

both as a human

and as an artist,

an inevitable threshold I had to

cross.

In the past few days,

I began perceiving

a form of static energy.

I saw my hands

while blind.

I discovered a key.

Now looking back

cocooning seemed to have played

a big part in this process.

Sometimes I wish

to go back

to this place

for I seemed to be more happy then

than now

for some reason.

Perhaps resetting

in full swing

allowed me to cross the bridge.

Although I was alone

I never felt lonely.

The visitors of Istanbul

lent me such kindness.

Their smells,

their whispers,

their kind footsteps,

their energy of genuine respect.

I fell in love with this city,

I felt

nostalgic

every second

after I left.

Throughout

I carved words

into the bricks.

My last

before

I destroyed it:

Don’t

Look

Back.

Carlos Martiel

Performance artist Carlos Martiel uses his body to address the lived experience of the Black male body. Born in Cuba, where he graduated from the San Alejandro National Academy of Fine Arts, he now splits his time between New York and Havana. Here, he chose to have the following interview, first published in Hypermedia magazine, translated into English. His interviewer is the Cuban-American artist, writer and curator Coco Fusco, who has also used her body to confront racial representation and colonial legacies. Together, the artists talk about the origins of Martiel’s family, his interest in blood as an expressive material, and his sculptural focus in performance.

Words COCO FUSCO

Carlos Martiel has created some of the most striking performances ever made by a Cuban artist. Over the past 15 years, he has transformed his body into a symbol of subjection, survival and collective resistance, with memorable renditions of the stories and experiences of those who have been marginalised and displaced.

I became acquainted with Martiel’s work through my dear friend and colleague [Cuban artist] Sandra Ceballos. Its sheer, raw imagery impressed me: his bleeding arms extended, his head under a soldier’s boot, his eyelids covered in excrement. It looked as if he were slashing himself, scarring and submitting his flesh to distress without a second thought.

Back when I was writing a book on performance art and its links to Cuba’s political arena, I knew I had to

include a discussion about Prodigal Son, the performance in which Martiel pierces his own chest with his father’s revolutionary medals in an unforgettable commentary on the price paid by those who volunteered for the Cuban Revolution.

Since his departure from Cuba in 2012, Martiel has extended his historical references to address his experiences in Latin America, Europe and the United States. He has reappropriated the masochistic tendencies of body art in the 1970s and repurposed those gestures as political allegories of the social condition of Black bodies throughout the African diaspora, evoking stories of slavery, subjugation and deterritorialisation.

Coco Fusco: Your ancestors were Jamaicans and Haitians who arrived in Cuba as farm workers. How does your background influence your artistic practice?

Carlos Martiel: I come from the offspring of Jamaican and Haitian immigrants who settled in Banes, in the province of Holguín, in the mid-1920s, to try to get by. As a kid, my grandmother used to tell me, at bedtime, the experiences of her early childhood and all the hardships and upheavals that her parents had to go through in order to raise nine children, before they could move to Havana. I really enjoyed collecting all those memories from her. Despite the challenges present in her stories, she always shared them with a sense of pride.

In time, as I matured, my Haitian and Jamaican roots became a fundamental pillar in my life, so much so that I applied for Jamaican citizenship four years ago.

Evidently, being an artist, and doing work focusing on the body, identity and immigration, I have come to make different works relating to who I am, because art is a process of individual affirmation, as well as of ancestral acknowledgment. In recent years I’ve made pieces like Legado [2015], Basamento [2016] and Muerte al olvido [2019], all of which explore my search for an identity, the recovering of my family history and the memory of all the bodies that are a part of me.

CF: How did you come to leave Cuba and find a base in another country to develop your artistic work?

CM: I made the decision to leave Cuba when beginning my second year at ISA [Instituto Superior de las Artes, Havana]. At the time I wanted to make the most of my possibilities in life, I wanted to travel through Latin America, and I yearned for a world that the Cuban context kept dismissing for me, due to its restrictive reality. I felt repressed in my own country. Deep down, I knew I was an artist. The main element of my work was my body and experience, so I didn’t overthink what could happen to my work outside Cuba, because I felt that I was my own work material.

CF: Your trajectory could be divided into stages – your years in Cuba, your departure and time in Ecuador, and your migration to the United States. What were the most important experiences you had in each one of these stages?

CM: The most relevant part of the first phase of my work in Cuba was the discovery of my body as a tool of work, which led me to the use of blood. When I began studying at the academy I made a series of drawings with different media – coal, beeswax, iron oxide diluted in vinegar and my own blood. Of all the materials I used, blood was the most constant one and the one that became, little by little, a prominent feature in my drawings.

For the blood drawings, I had to go to clinics and ask the nurses on duty if they could do it for me as a favour. Which in time became a hindrance, because they only drew very little blood or refused to do it altogether, since some of them questioned the use I intended for it. The time came when I wanted to make a specific type of work and couldn’t, because I was lacking the material that I was conceptually interested in using. Still, given the issues that I was drawn to, that frustration made me understand that the way to keep working was my body, and that’s how I decided to begin to do performances and make myself the object and subject of my own practice.

Quito and Buenos Aires were a trial for me. If something is to be said about that period in my work, it is my capacity for resilience when exploring the unknown, remaining faithful to the path I had drawn with my body.

When I arrived in Ecuador I had already made some works, but my departure from Cuba took me out of my comfort zone. I was completely destabilised when I faced the challenge of knowing what to do in order to keep existing as an artist without diluting myself. During that time I realised that the most important thing in my work was context, and that confronting what I didn’t know could provide a lot of material for it.

That is when Cuba became a thing of the past for me and I began to make a series of pieces in which my experience as a migrant became the centre of my creative focus. Coming to the United States was another moment of destabilisation in my work, but I came to terms with it because I had already experienced life in other countries.

What I can say about the past few years of work is that I now feel the extent of the responsibility it has acquired when meeting the demands of a specific context, and the commitment that I feel to my voice as a Caribbean immigrant, a Black person and a homosexual.

CF: You have said that if you weren’t a performance artist, you would be a sculptor. What does performance offer you as a medium? Why focus your energy on it in particular?

CM: I see the performance artist as a sort of behique, a pagan saint – and I don’t mean those that stand on altars – a scapegoat, an intellectual terrorist. When art is born out of the need to express the inner conflicts of human beings, it’s able to connect with whomever, regardless of your birthplace, your skin colour or your gender. The ritualisation of the body through art creates empathy.

In my experience, performance has been the medium to manifest my needs and rights, as well as those of others – the universe of the oppressed is all too large. Working with and from my body has been a process of individual empowerment.

The path of the body has not been easy for me, because as an artist one feels the world in a different way. A creator lives tormented by meaning and sometimes this overflows – you don’t know what to do with everything you know you have and must express in some way. Coming to the conclusion of making performance art and working with my body was a cumulative process, which emerged from my non-conformance with different types of realities that I came across. I was a teenager with many questions regarding what it means to be Black in Cuba. I was ashamed of my sexual orientation and felt suffocated by the social and political circumstances of my country and my inability to change them. Performance was my salvation, my act of self-liberation and resistance, and it still is to this day.

CF: Your main medium is your body as an object. You don’t use your voice, and in most of your pieces you barely move. You invite us to behold your body being manipulated in various ways – perforated, sewn up, bloody, buried, restrained. Can you elaborate on the bodily metaphors that are predominant in your work?

CM: That’s why I said once that had I not become a performance artist, I would have been a sculptor. Through performance I’ve modified my body and mindset, just like a sculptor transforms a piece of marble or wood.

My work is born out of an individual dimension, often autobiographical, that acquires a social dimension during the creative process. It’s a permanent exercise of corporeal sincerity.

In performance, one can say a lot with no words or gestures, because the body’s possibilities are endless and bodies don’t require speech to understand each other. The bodily metaphors I make and use to produce sense and share knowledge are just the way in which my mind processes my reality and that of other bodies which I feel deeply connected and attached to.

CF: How do you approach your vision and experience of Blackness in Cuba, and how different is it from what you went through abroad?

CM: From birth to death, beinga Black body is and will be a permanent struggle, not out of choice, but because racism is the foundation of most contemporary societies and violence against Black bodies is a global phenomenon.

After leaving Cuba I had the opportunity to live in three countries – Ecuador, Argentina and the United States. Despite having to, more often than not, confront racist people to extents I would never have imagined before, the racist experiences I suffered in Cuba had the most impact on me, maybe because they happened while I was growing up and getting an education.

I remember that there was a moment in my teens when I wouldn’t walk out on my own around Old Havana or El Vedado, because I used to get stopped by policemen at every corner. As a child, I also recall that most of the jokes made by my friends aimed to ridicule and humiliate Black characters. I remember that the word “negro” was used against me as an insult countless times, as if being Black were a criminal offence or something to be ashamed of. “Negro y maricón, lo último” – a popular saying in Cuba that could translate as, “Black and a faggot, that’s rock bottom.”

I look back at all of this now, because I’ve had to revalue my body, embrace the jewel of my Blackness and come to understand that there isn’t a single problem with my being Black. But in my childhood and teenage years I didn’t have the tools I have now to defend myself.

Living in the United States and experiencing first-hand the harsh reality of racial inequality, an immeasurable anger builds up in you. I’m not telling you anything you don’t know or haven’t experienced yourself. Racism has destroyed too many lives here, both literally and figuratively. Racism here is a daily experience because people allow themselves to be racist without thinking for a second about what is wrong in their behaviour.

If I have learnt anything in the United States, it’s that my rights and my life are worthy, and that any effort I might make to fight racism will fall short. There is no such thing as second-class lives, therefore we can’t keep accepting our bodies vulnerablised, fragilised or assassinated.

Translated by Adrian de Banville

Paula Garcia

Brazilian artist Paula Garcia explores ideas of resistance in her work, building her creative process through rupture, denial and uncertainty. In the following essay she discusses Noise Body, a performance during which she is locked into a suit of magnetised armour and covered in heavy metal objects, before a group of collaborators throw handfuls of large nails at her. The jagged sound of metal colliding with her armour ricochets around the gallery space until Garcia can no longer stand under the weight of material.

In her subsequent work, Crumbling Body, the artist again harnessed magnetic forces, which act for her as an analogy of the invisible forces – social, political, psychological – that control us, as well as a way of exploring both the limits and the strengths of the human body. Garcia also works as an independent curator and a project curator at Marina Abramović Institute.

Noise Body

In performance art, the confrontation is direct, especially between you and your limits, and that is what I wanted to work with. I gradually realised with this practice how the work modifies me, even more so because most of the experiences consist of placing my body in situations of discomfort or contradiction. When I wear the armour in Noise Body, there is no way of knowing what will happen. I had not managed to wear it for the duration of any of the rehearsals before I performed for six hours for the first time in 2014, for the exhibition The Artist Is an Explorer, co-curated by Marina Abramović at the Beyeler Foundation in Switzerland. The suit of armour had to be locked with a key and I felt claustrophobic in all preparatory attempts. But during the performance, I managed.

The experiences of the Noise Body series really modified me. Crumbling Body, the work I did during the exhibition Terra Comunal, in 2015 in São Paulo, was extremely challenging. The action of gathering scrap metal with magnets confronts the sensations of heaviness and lightness. The walls and ceiling were impregnated with magnetic force; as the parts and debris spread, a kind of inverted burial space happens. For two months, six days a week, eight hours a day, I worked in this room throwing iron waste, up to 30 kilograms, at the magnetised walls and ceiling. After filling the walls and ceiling, the pieces were removed and placed in the centre of the room and thrown on the walls and ceiling again.

“ ... in a society where the non-white, female, queer and trans body is constantly at risk, there is something eerily protective about seeing Garcia’s body covered with layers of metal” – Rui Chaves, Making It Heard: A History of Brazilian Sound Art

I am aware that if I had not attended Marina’s Cleaning the House workshop shortly before the beginning of the exhibition, I might not have been able to experience things as I did during Terra Comunal with such commitment. Every day I used elements and practices we exercised in the workshop. For me, the mental confrontation is much more challenging than the physical confrontation. More than throwing metal parts against the wall, I am throwing energy.

On the first day of the performance, I used a lot of force and I hurt myself. I was excited with all the energy. The following day, Marina called to tell me she wanted me alive. This talk of hers, as an artist and friend, was so important. She spoke about my presence in the space, saying that even if I slept there three days in a row, it would still be intense. Over the following days, I started incorporating the silences and pauses as part of the process. I now realise that I lived through a period in that box in which there was a profound truth, with no deception. There was fury, obsession, fatigue, and there was an exchange of potent energy – “Everything that you, as an artist, transmitted in that space, people received back,” Marina said. Those teachings will undoubtedly be part of my legacy in the future.

“A tension sets in between a body that is brittle and malleable, and metal, which is firm and rigid. And the sound arising from it comes from a mechanical, material connec- tion between these metallic objects as they fall to the ground. Thus, the aural dimension in her works does not depend on the audibility of sounds. Sound hovers over the performances and imposes itself as a powerful presence” – Lílian Campesato, Making It Heard: A History of Brazilian Sound Art

The concept of Noise Body represents a body that is defined by a sum of three factors: precariousness, uncertainty and risk. The magnets are elements of my work that serve to discuss the concept of forces. Not only of the invisible subjective kind, but also of the more evident social forces that work to consolidate a system of power that ends up shaping things like bodies, feelings, subjectivities and truths. In these performances I try to showcase bodies in disassembly, crumbling. Ultimately, what I propose in my actions is a performative use of my body as a platform where different forms of conflict are carved out. At the end of the performance, when I would attract the iron pieces to my body, the result was an image of the system and of the body fettered, buried, like a body with no organs. At the same time, I emerged much stronger.

Regina José Galindo

Born and raised in Guatemala, Regina José Galindo has been writing poetry since she was a teenager, and later used many of her texts as the foundations of her early performances. With the country’s context as a starting point – in particular the bloody history of Guatemala’s 36-year civil war – she explores the ethical implications of social violence and injustices related to gender and racial discrimination. Galindo uses her body to transform her outrage into powerful public acts, such as the performance ¿Quién puede borrar las huellas? (2003), in which she walked barefoot through the streets of Guatemala City, repeatedly dipping her feet in a bowl of human blood to protest the presidential candidacy of former military dictator Efraín Ríos Montt. Here she chooses a small selection of her poems for Document. As carefully constructed as her performances, they are works that question whose voices and stories get to be heard and how to speak of violence.

we will defend

We’ll defend ourselves

with our fists

our nails

our teeth

our vocal cords

our vaginas

our uteruses

our ovaries.

We’ll defend ourselves with truths

ancestral strengths

changing moons.

We’ll defend ourselves with poems

weavings

drawings

voice.

We’ll defend ourselves, each

and every one of us

because together we’re one

and without even one of us

we won’t be all of us.

We’ll defend ourselves, all of us

before we all fall

and not a single one of us

remains.

Vamos a defendernos entre todas

y cada una

porque todas somos una

y sin una

no somos todas.

Vamos a defendernos entre todas

antes de que todas caigan

y de nosotras

no quede ninguna.

hundred seeds

For every cornfield you burn

we’ll plant a hundred seeds

For every foetus you kill we’ll raise a hundred

children

For every woman you rape we’ll come a hundred times

For every man you torture we’ll embrace a hundred

joys

For every death you deny we’ll weave a hundred

truths

For every gun you grip we’ll make a hundred

drawings

For every bullet lost a hundred poems

For every bullet found a hundred songs.

no one silence me

They follow me as I walk

and no one silences me.

They stop me in my tracks

and no one silences me.

They’re my shadow

and no one silences me.

They kick at my dignity

and no one silences me.

They tear my name to shreds

and no one silences me.

They make up lies

and no one silences me.

They put me in jail

and no one silences me.

They accuse me of everything

and no one silences me.

They explode me with shouts

and no one silences me.

They insult my blood

and no one silences me.

They throw me in a pit

and no one silences me.

They steal my light

and no one silences me.

They shatter my teeth

and no one silences me.

They pull out my molars

and no one silences me.

They gag my mouth

and no one silences me.

They cut out my tongue

and no one silences me.

They burn my face

and no one silences me.

They tie my hands

and no one silences me.

They slice at my feet

and no one silences me.

They dig out my eyes

and no one silences me.

They yank out my fingernails

and no one silences me.

They brand my skin

and no one silences me.

They spread my legs

and no one silences me.

They come inside me

and no one silences me.

Blood seeps from my veins

and no one silences me.

The punches hurt

and no one silences me.

They crush my intestines

and no one silences me.

They stab me through the heart

and no one silences me.

I go dry with thirst

and no one silences me.

My dreams kill me

and no one silences me.

They kill me with hunger

and no one silences me.

They kill my life

and no one silences me.

They try to erase me

and no one silences me.

The voice

– my voice –

comes from somewhere else

from deeper within.

They

haven’t understood it.

Yiannis Pappas

The Berlin-based artist Yiannis Pappas was born on the island of Patmos, Greece, famous for being the site where the Bible’s apocalyptic Book of Revelation was written, and where a Unesco-listed monastery has stood since 1088. It’s a connection with religion and nature, the sacred and holy, that has surfaced in his work – his master’s thesis was based around five weeks he spent in a monastery on Mount Athos in 2013; his piece Holy Vestments (2009) took the form of a robe made of golden ping-pong balls that was inspired by a Byzantine emperor. Working with video, photography, performance and installation, Pappas creates work that is underscored by a critical interest in space – as sites of physical and symbolic enactment – exploring how different places are sustained collectively and individually throughout history. Here the artist discusses Telephus, a 175-hour performance that took place at the Bangkok Art Biennale, in which he methodically wrapped parts of his body in plaster, eventually building a mountain of casts into a monumental sculpture.

Telephus

A Possible Island?

Bangkok Art Biennale, Bangkok Art and Culture Centre

18 October – 11 November 2018

The body can be used as a powerful tool. I use it to conceive sociopolitical genealogies and statements; it is the medium through which I visualise ‘body politics’ as it has been established in today’s society. Through my practice I observe how state institutions enforce abstract power interests over the individual by way of accessing our biologies. My works are site-specific performances that seek to leave traces of temporality throughout mythological or historical events.

In the case of a performance artist, the human need for legacy could be considered the implicit knowledge that is transferred from body to body and operated beside any form of tangible material boundedness. Ultimately, the shared experience of the performance act is all that remains.

For the 175-hour performance I presented at the first Bangkok Art Biennale for A Possible Island?, the live exhibition curated by MAI, I was continuously and repeatedly wrapping different parts of my body with plaster. I ended up with a huge pile of cast parts that had been removed from my body and formed a sculpture in its own right. The act of wrapping my body parts with plaster alluded to the Greek myth of Telephus. The words Ο τρώσας και ιάσεται, an ancient Greek proverb meaning “Only he who inflicts the wound can cure it,” refers to a prophecy that was given by the oracle of Apollo to Telephus about the way he should heal his wounds caused by Achilles. After the completion of the performance, the cast sculpture was donated to the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre.

A second reference of this performative work alluded to a statement made by Georgios Papadopoulos, the leader of the junta that ruled Greece from 1967 to 1974. In a statement, Papadopoulos described Greek society as a “patient” and assumed for himself the role of medical doctor. As a doctor with knowledge and authority, he would save the patient’s life by restraining them on a surgical bed under anaesthesia to perform the operation. This, he suggested, was the only way to not “endanger” the life of the patient during the operation.

This statement became known as “Greece in the cast”.

The medical practice of anaesthesia and the immobilisation of the patient through the cast were here presented as a necessity for Greek society to recover from its illness. Despite not knowing the Greek context, much of the audience in Thailand received the coded message, translated through the performative act and the medical references. Many people identified their own sociopolitical experiences and struggles in those of Greece.

Through these two references that informed the work – the myth of Telephus and the allusions to military regimes – I see two forms of legacy. In the first case, a material memory of the performance was donated and archived in the museum. The second case concerns an immaterial legacy, a genealogical political solidarity that was shared between me and the audience in Thailand. The paradoxical act of casting my body, of seeking to ‘fix’ it, to ‘civilise’ it, offers a critique on the ways personal asphyxia can be transformed into a collective one.

The pandemic showcases human imperfection brilliantly, as well as our inability to embrace our existential position in the one and only environment where we all belong: nature.

One of the oldest and strongest emotions of mankind is fear. Covid-19 gives us a chance to confront the concept of memento mori (remembrance of death). At the same time, it makes us think about our individual legacies. The idea of temporality through my performative body work is what I wish to remain of me. When a long-durational performance is over, my state of mind focuses on understanding through the sharing of immaterial temporal indications that affect human life, such as the shared experience with the audience in Thailand.

In long-duration performance, the audience is also the body of evidence: it is a part of the legacy while a collective participatory memory is created. Beside the traditional forms of documenting such a performance (videos, photographs and traces/objects of the action) there is the collective experience between the performer and the public – which might become a polyphonic tribute or a shared testimony to the actuality of the work.

Estileras

Boni Gattai and Brendy Xavier are Brazil-based performance, transdisciplinary and multimedia artists working under the name Estileras. Their practice subverts traditional fashion structures, questioning the exclusivity and secrecy that permeate the market. They are interested in experimental actions, in the relationship between improvisation and material creation, and in collectivity as a tool for changing and powering an artistic network. Their performances are often supported by live videos, photographs and soundtracks, and involve creating anarchic, wearable art out of recycled garments. Here they describe Monster Shoes, a six-hour performance in which they cut, spliced and stitched discarded shoes into Frankenstein-like layered, mutated platforms, posting the creation of each new ‘monster’ on Instagram in real time, broadcast live through Marina Abramović Institute.

Calçados de Monstro (Monster Shoes)

The improvisation involved in creating an outfit for a party was the start of Estileras – the point where self-expression meets reality. The impulse of translating the excitement and anticipation of a night out revealed a pattern of deconstruction of clothing, a glimpse of a practice where the aesthetics are defined by defiance.

By finding new ways to wear old clothes, playing with already-made stitches and using our limited mastery of sewing (safety pins everywhere), fashion conventions can be twisted. We found that performance was the perfect space for sharing our process while also embracing the risk of reality, letting errors into our not-so- final works.

For Calçados de Monstro (Monster Shoes) we created a live web series of the same name where the premise was to set a time frame during which we would create things for our feet with what little we had available. It was an open performance where the results would be a surprise not only for the viewers but also for ourselves. And through livestreaming we were able to incorporate video as a part of the performance – rather than just recording an act, the act was only possible because there was a camera with us. The camera called on us to perform for it, to open our movements and ideas to the world. It was a nod to experimenting with reality as a medium. Maybe by letting art be part of life we can deglamorise fashion and access its processes.

This feeling of letting time and space limit the action to produce something that pulses with improvisation and experimentation is present in everything we do. And with it, the necessity of bringing our friends with us, bonding connections through collective bodies of work. It is obvious that almost every form of art we consume – movies, music, shows, and so on – is inherently a collective text. So why do we often spotlight only a few nodes in the network when the potential of a project is defined by the commitment of those involved? Especially with fashion, the designer is always paramount, while the rest of the team have to be satisfied with written credits at the end. From this clog in the machine, we went looking for alternatives and ways to make every part of the engine recognised as being essential. This led to Estilera Fudidamente Inserta (2019–2020, at Casa de Criadores in São Paulo), a three-part project, in collaboration with art collectives Inserto and FudidaSilk, where there was no backstage, no face unseen, no name unheard nor any link unattached. For a whole day we opened every detail to the public, followed by a runway show where the models and staff walked together down the stage.

What we have now could not have existed without the effort of those before us, and all that will be from now on will also have a mark of our presence. Connections are endless and have no boundaries, they tie the past, the present and what is coming to be with everything that is externalised and created. A ramble of nodes. If we could touch these lines that put us in contact with the world, tie them together, we might unveil a glimpse of the invisible.

From the collage of materials and the assembly of people we’ve created objects closer to the uncertain and difficult aspects of life. Their online history aims to shine a light on all the other lines.

Halil Atasever

Turkish artist Halil Atasever grounds his practice in reflections of the human condition. Using familiar objects such as fabrics, prayer rugs or clothes, he seeks to establish a clear visual language that reveals multiple layers of meaning during his performances. Here he describes his work Slaughterhouse, a confrontation with white-collar identity and its promise to provide protection and prosperity while increasingly tying employees down. Cross-legged on the floor of a cavernous gallery space in Istanbul, Atasever quietly unpicked the seams of dozens of white shirts, laying each piece of fabric on the floor until they created a vast, imprisoning mosaic. The meditative performance was part of Akış/Flux, a collaboration between Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Akbank Sanat and Marina Abramović Institute.

Slaughterhouse

Akış/Flux, Sakıp Sabancı Museum Istanbul

17 November – 13 December 2020

Slaughterhouse was a 22-day long performance: the main act was to unstitch 52 men’s white shirts with a seam ripper six hours a day in front of a dark blue wall.

It was a fascinating opportunity to perform a long-durational piece curated by MAI in Sakıp Sabancı Museum. And a tiring experience as a whole. Waiting for the driver to give me a lift to the museum, watching the streets sliding by, passing the Bosphorus Bridge and finally reaching the museum in the middle of the pandemic. Changing clothes, going to the toilet one last time and starting to unstitch. Six hours a day, the same action, over and over again. Arriving back home at about 7pm. Eating healthily with my elderly diabetic mom and watching TV.

MasterChef Turkey is on our relatively small living-room TV. The contestants on the screen are trying to cook the best surf and turf in under 50 minutes.

During the performance, cutting the shirt threads was the gateway to my deepest pitfalls. I do not know if it was supposed to be, but every day was a new therapy session in which I constantly faced off my rooted ideas of being a man, being an artist, being a son. As if it isn’t hard enough to be a human, these layers all bring addi- tional necessities, like to-do lists, phone alarms, contracts. But how many of them really work?

With a few apples left on the side table, I’m trying to forget everything I thought while unstitching the shirts.

One of the contestants is making parfait using okra. Surprisingly.

A performance itself is basically the guardian of Dionysus. Upon thousands of years of cultural history, I find it confusing to draw the line between rational and irrational. Apollo is not Apollo any more.

It took me a while to detach myself from postmodern theories and go back to the basics. I can never embrace the uniqueness of personal thought when the world is full of people suffering from lack of access to drinking water. Whatever identity we carve out from our organic body, however we fully decorate our perceived self, it is not worthwhile unless we feed someone who is hungry.

Dad, where are you now? They are cleaning fish on the show, and I remember as clear as daylight how you loved eating sardines.

I lost him nearly three years ago and we will never eat fish together again.

It all started with him. The son of an immigrant family whose main source of income had always been fabrics, mainly men’s shirts – now his son unstitching shirts to rationalise himself.

He always wanted me to be a lawyer or a manager in a multinational company and never lost his hope to see me in suits. He saw it too. I could never let the economically uncomfortable side of being an artist hunt me down. Moreover, it has been beneficial for me to work as a white-collar worker from time to time.

The battlefield is hidden somewhere in my mind. The stories and the teachings of my dad are doing their best to attack my deviant plan to be a ‘well-known’ and ‘established’ artist. There has never been a true winner of this war and there probably never will be.

My mom asks who won the previous round. The red or the blue team?

I moved to London nearly four years ago. Established my design business and have survived quite well so far. However the crucial question that appeared and struck me every day during performance hours was what to do next when I go back to London. Oh no – please don’t tell me I cheated on the purity of my performance and dived deep to probe daily problems while performing such a sacred piece. It always comes as a package. Doesn’t it?

Once a week they shoot the show in a different city in Turkey. The teams are trying to cook the best local dishes. Another city, same contest.

Married couples, mortgage rates, travel plans, all these things I admire in some ways, and I am disturbed by knowing that they will probably never cross my ongoing path. None of the rational plans of modern life build a narrative upon touching ‘another’.

Trying to walk the thin line of self-centred, self-dependent stories of ours and the commonalities of these stories with others. The others. Something we learn during our childhood. As we are detached from our mothers, our being is totally out and separate from another being. Is it? If we cannot construct the outlines of our body blending with another entity, why do we even work so relentlessly to leave something behind? The trigger points, all we can sew with our bare hands.

One of the contestants cuts her hand with a meat knife.

The world is full of rational ideas and logical explanations. Becoming more and more self-centred. The encapsulating presence of science and technology gave us cellphones, hospitals, spaces. But the buildings collapse, organic stuff rots, icebergs melt – more than ever now. Temporariness in its finest form.

I care about my irrationality. Bending the rational with irrational actions. Trying to form a new essence. Attributing new meanings to the objects. Defining new thought realms. Creating trigger points. Believing the capability of leaving a mark on the receiver’s mind.

It has been a 22-day transform- ative journey.

And still I have not tasted surf and turf.

“There is a vitality, a life force, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and there is only one of you in all time. This expression is unique, and if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium, and be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is, not how it compares with other expression. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open. You do not even have to believe in yourself or your work. You have to keep open and aware directly to the urges that motivate you. Keep the channel open. No artist is pleased. There is no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer, divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others” – Martha Graham

This story appears in the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine which is on sale now. Head here to purchase a copy.