Art In Relation: how can art allow human beings to live together sustainably and in relation with one another? In this series, Chinese-Canadian curator and writer Kate Wong speaks to artists working across performance and film about the role of storytelling in their practices and about creating work that allows us to come together in a world that tries its very best to keep us apart.

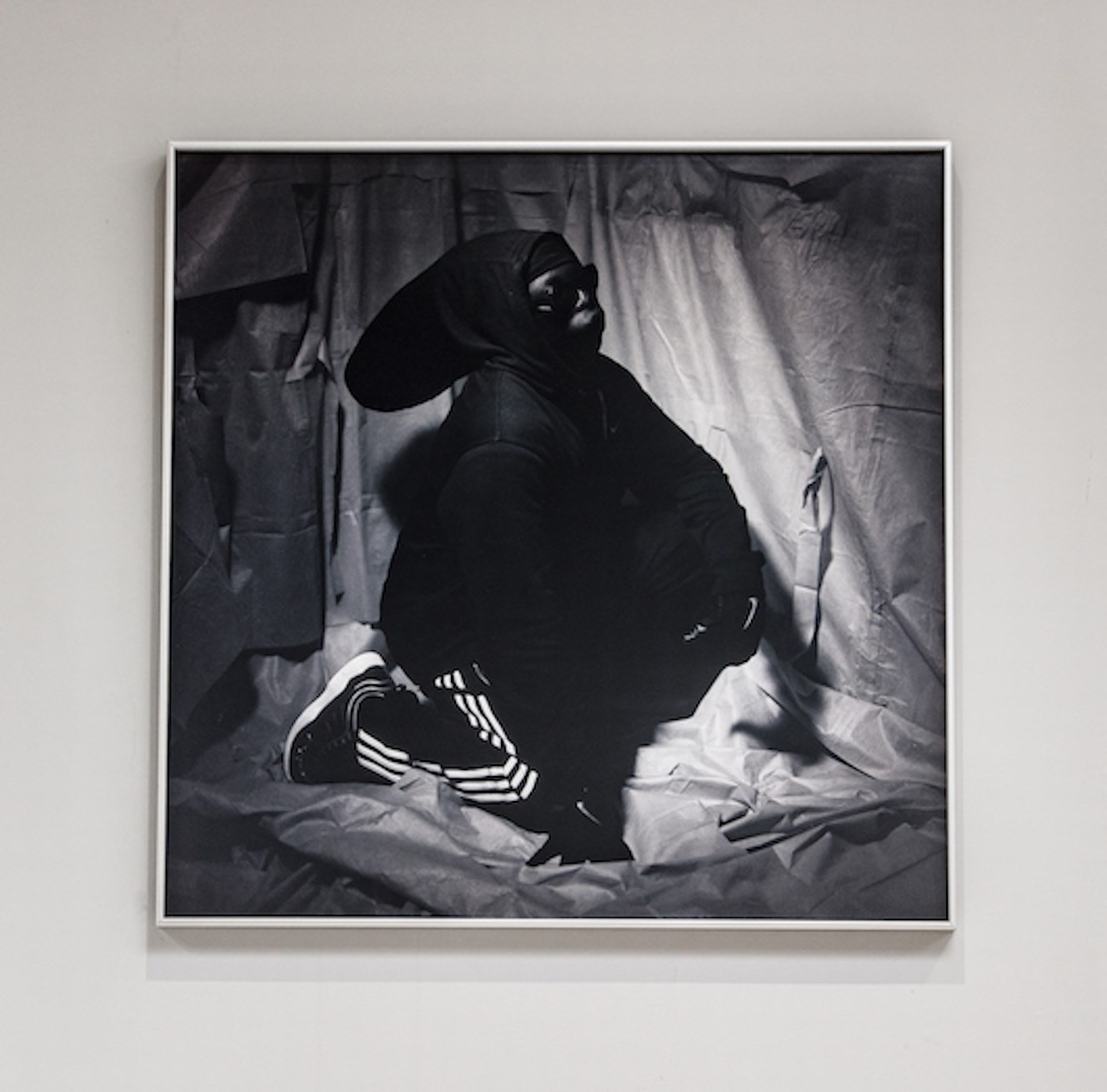

R.I.P. Germain is a multidisciplinary artist whose work is committed to interrogating oppressive power structures and their impact on Black life. Traversing mediums including installation, photography, performance and most recently, film, his practice takes a forensic approach to exploring themes of ritual, loss and mourning.

Across projects such as his solo show Gidi Up at Peak (London, 2018), Double 6, a durational performance with Ashley Holmes in the Leeds Town Hall (2019) and a performative installation J.D.D…S.Y.M (Farin) made for a group exhibition presented by Arcadia Missa at NICO (Bari, 2020), R.I.P. Germain places an onus on the audience. As much as his practice is self-reflexive, it is also energised by audience subjectivity and participation. The artist creates work that, in spite of its cultural specificity and often challenging nature, facilitates a kind of broad consciousness-raising.

I sat down with R.I.P. Germain following the recent opening of his solo exhibition at VO Curations, Four Bedrooms With An En Suite, A Garage & Garden In A Nice Neighbourhood. In this conversation, we discuss the role of storytelling in his work, notions of social and cultural bridging, the function of objects as vessels of communication, and his new film, mew, which is both a return home as well as a look into African-based religions within the Caribbean.

Kate Wong: You’ve had to speak a lot in public recently, haven’t you?

R.I.P. Germain: That’s why I’m making the work! To have these conversations with the audience. So talking about it and talking about it and talking about it, it’s part of the journey of the works – the life that they have.

KW: What role does storytelling play in your work?

RG: Storytelling plays a big role for me. It’s the bridge between the topics I’m discussing and audience understanding. Storytelling is the context for the work I make. For example with the work in my show at V.O, Mucktar ⇄ Latwaan & CrossIon (? FAIR TRADE?), there is a story behind it that reflects what is going on with young Black teenagers in London, and my way of telling this story highlights this as an example of system making. It also shows how to individualise things. It’s easier for the audience to digest really esoteric or complex ideas, as well as the commentary I’m making about society, through a story.

KW: A lot of the content and context in your work comes from personal experience. Can you speak more about this idea of ‘individualising’?

RG: When you layer a work in relation to a specific person or specific demographic, you can then point to it as an example. If a work is based on a specific person, this allows the audience to do subconscious things like placing themselves in the position of that person. Individualising is a way of mirroring, subconsciously. It’s a way of building empathy, another form of bridging.

KW: So storytelling is a way to individualise, to bridge the gap between people and their varied experiences?

RG: When I talk about individualising or specificity, it’s to draw an emotional response from an audience. With the work I’m making there is a personal story to it that’s never explicitly stated, and more often than not, if an audience member walked in coldly they would not know that. But the cultural references I’m making, they may be little bits that can be latched onto, even those are really niche and specific to people involved in various cultures, like UK drill or parts of African-American subcultures.

KW: Like the work CJ (Keeping Up Appearances), which draws attention towards representations of Black masculinity within western society through the character of CJ from Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, or the fantasy of Tupac in a business suit?

RG: Yeah, like the CJ thing and the Tupac thing, even the cake soap thing and the story of Vybz Kartel and how he became the flag bearer for skin-bleaching in Jamaica. And how he made a song dedicated to cake soap and all of those things. Storytelling is not as linear as me trying to simply tell something to the audience. I’m showing something to them through an item that represents a story. The aesthetic qualities of the work, the types of materials I use, are also a way of connecting to the audience.

KW: This is a defining aspect of your work for me – the idea of items or objects that function as codes. The creation of a system of communication and knowledge based on objects whose meanings are not always readily decipherable, or at least not by everyone. There is an element of withholding, but even more importantly, an aspect of creating work for people or groups of people whose stories are not discussed within mainstream discourse.

RG: Exactly. One example is when I had a show at Cubitt, where I put in beaded curtains as a spatial divider. That’s something that is understood by a whole load of diasporas. Everyone has an auntie who has beaded curtains in the kitchen. Some people may not get that reference, but others did and it was a way of collapsing the hostility that comes with gallery spaces, and to bridge a sense of familiarity in a space that can be very alienating.

“I feel a lot of people have their egos and pride tied to their opinions. There’s a lack of elasticity to evolving your opinion” – R.I.P. Germain

KW: You mentioned aesthetics. How would you describe yours?

RG: I’m a maximalist, so my installations usually have multiple, complicated components. I work on each component separately and I don’t really decide the composition until I get into the space. I then instinctively navigate the space based on what I feel – on how the objects hold themselves together. How does this object work best against other objects? I do preliminary sketches but I’d feel a bit weird if a completed work looked much like what I intended in the beginning.

KW: What is your relationship to the found objects in your work? Is it ever emotional? Is there maybe an aspect of attachment?

RG: A lot of these items have loaded, heavy meanings and I make a lot of coded references by using them and placing them within an artwork – especially as they come together in a group. When I make the work, there’s actually a kind of numbness for me. There is so much meaning I am imbuing into the work that, if I’m totally honest, I end up having a level of detachment from them.

They [the objects] become everyone else’s. The work has two lives. The first is with me, when I am making it. The second is when it goes into the exhibition space and is reborn when the audience interacts with it. It reincarnates.

KW: That’s a very spiritual way of thinking about the life of an artwork. So you’re forming your alphabet with objects, which perform the dual function of telling a story and forming a bridge with your audience?

RG: Exactly. The objects are usually just vessels for a different discussion. I’m hardly ever using an object as it exists. It’s like I’m a grime bootlegger, taking something that exists and remixing it, manipulating it in a way that I want it to look and feel. It’s like a mutation, in a conceptual sense, through meaning-making.

KW: A mutation – great word. Congratulations on winning the ICA Image Behaviour Award, by the way. This is your first time making a film, isn’t it? What’s the title and what is it about?

RG: The film is titled mew. On one side, it’s a re-rooting with my cultural heritage, being from the Caribbean, and on the other side, it’s an investigation of African-based religions in the Caribbean, and being a part of those communities temporarily. I’m capturing people from these communities – for example, people from the Orisha faith – as they are and as they want to present themselves. A lot of their histories are awash with colonial propaganda. There’s a lot of stigma attached to their communities and religion. A lot of the film involves myth-busting. It gives space for them to tell their histories and their culture in their words, which is not done that often.

“The central point at all times was a practice coming out of love or a need for building and strengthening one’s community” – R.I.P. Germain

KW: Has the process of filmmaking opened up your storytelling process?

RG: It’s opened the door for new topics I want to talk about and conversations I want to have. The film involves interviewing people. Where previous interviews in my work were for the purpose of preserving and archiving, these interviews are about seeking out new knowledge.

KW: So filmmaking has been more of an external exercise than you’ve engaged in previously?

RG: Yes absolutely, and it’s the first time I’ve been patient with a work and been completely intuitive. With this film, I wasn’t able to take control in the same way as when making an installation. I had to rely on and work with others. I had to let the process of the film unfold the way it needed to unfold, in a very sort of soft way. It was a personal exercise in letting go and being able to share control in making art.

KW: Based on what you told me a few weeks ago, it sounds like the filming process was a mystical experience.

RG: It was nuts. One of the crew members changed their whole perspective on religion.

KW: What happened?

RG: All of the crew were very open minded towards what we were shooting, but what we saw on the first day … if we hadn’t captured it on film, you wouldn’t believe it. After that crew member got home on the first day he was, not culturally shocked, but truly in a ‘what the fuck’ state. We saw so many things, experienced so many things.

KW: Wow, intense. Once you open yourself up to different frequencies, you open yourself up to what normally would be passed off as impossible, or at the very least implausible ... kind of the opposite of how we are in London.

RG: You naturally become closed in London. It’s ten times easier to make friends when you’re on holiday than in your home city. You’re more open to receiving.

KW: Exactly, receiving.

RG: It was a transformative experience. So many things happened on that trip. I got clarification on a lot of internal musings. I consider myself to be spiritual but not religious, and, during that whole trip, it was the first time that a religion made sense to me, you know? Just the way it was practised and what that meant for that community – practising it amongst themselves and with each other.

KW: Yeah totally. The idea that religion might not make sense outside of a particular context, but within a specific cosmology, it feels completely natural and like it almost has to be believed.

RG: Exactly, it comes down to how they were practising it. The central point at all times was a practice coming out of love or a need for building and strengthening one’s community. It was a really beautiful experience.

KW: And on this note about love and the strengthening of community, how can we as human beings not only live together, but live together sustainably and in relation?

RG: Letting go of ego and pride! Understanding is the strongest bridge when connecting with someone. Even if I don’t agree with you, if I make an effort to understand where you are coming from, there’s something we can work with. It’s about being open to understanding someone. I feel a lot of people have their egos and pride tied to their opinions. There’s a lack of elasticity to evolving your opinion. A lot of people are rigid in this sense, at this moment

People forget we are only here for X amount of time and then we’re gone. It’s not that deep. Let people just live and be who they want to be, as long as it’s not hurting other people, it doesn’t matter.

Four Bedrooms With An En Suite, A Garage & Garden In A Nice Neighbourhood is on at VO Curations until 24 March. mew will be screened at the ICA on 30 April 2022 with tickets available now.