Very Private: A new exhibition at Charleston House in Sussex presents a series of erotic drawings by Bloomsbury Group artist Duncan Grant alongside new work by six artists including Tim Walker, Ajamu X and Somaya Critchlow

A copy of Duncan Grant’s Erotic Art (1989) is held in the London Library’s safe. If you go to the front desk and ask for it, the cover is labelled: “Restricted Circulation”. Inside, on a random page, are five ballet dancers bent in a line in a gay orgy. “It’s rare,” the librarian says, “and valuable.” Published at the artist’s request, the book describes similar drawings sent to the artist Edward Le Bas, which after his death, his sister is thought to have burned. “Although there’s a rumour,” writes Douglas Blair Turnbaugh, “that another friend rescued the collection and that it will surface one day.”

That rumour is true. In October 2020, the retired set designer Norman Coates offered the collection to Charleston, the former home and studio of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, two of the most celebrated modernists in 20th-century British art. Made in the late 40s and 50s, when homosexuality was illegal in Britain, the work was kept hidden in a folder under Coates’ bed. Now, 40 of the 442 drawings are on public display at Charleston with Very Private?, the first exhibition of Grant’s lost erotic work. “The collection came to us through the Arts Council’s Cultural Gifts scheme,” says Nathaniel Hepburn, Charleston’s director and chief executive. “To qualify, we had to prove that the drawings are of preeminent importance to the nation.”

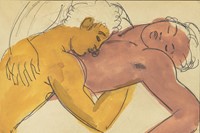

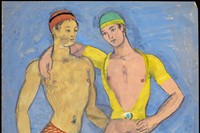

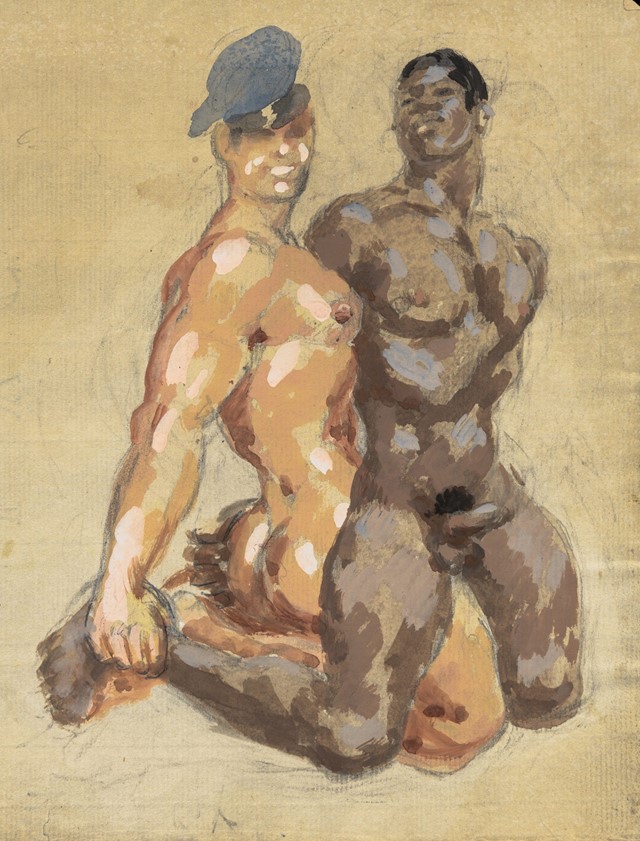

The drawings are presented alongside responses by six contemporary artists, including the photographers Tim Walker and Ajamu X, as well as a solo presentation by the radical feminist collagist Linder Sterling. “The works would have all been by Duncan Grant,” explains Darren Clarke, head of collections and research, “so all [made] by a white cis male. All his interests belong to the time in which they were made. There are a lot of interracial drawings. So they raise questions that meant we didn’t feel comfortable presenting them just as they are, unfiltered. We needed more voices in the room.”

The drawings by Grant are composed like a score. No line or limb is out of place, existing entirely for the part they play in the whole. It’s a quality captured by Ajamu X in his own celebration of Black queer bodies, arms in dialogue with legs, or Tim Walker’s shaping of bodies through lenses, angles and bottles. The best works are choreographed, posed. In Grant’s studio, still on a bookshelf is his photo of Vaslav Nijinsky, the legendary dancer of Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which Grant first saw in London in 1909. The work in the show knows one thing: good sex, like good art, is like dancing.

In 1916, Grant and Bell moved to Charleston, an old farmhouse in Sussex, which together they viewed as a canvas, painting the walls, tables, bookcases, tiles – any surface in sight – as well as the artwork that hung on the walls. As Simon Watney writes in The Art of Duncan Grant (1990), “he refused to accept the distinction between the fine and applied arts. Design was a term that might equally apply to pottery, or furniture, or murals, or easel painting” – or porn. Grant’s erotic drawings exist as an equally important part of his decorative art. As design, they could cover it all, the cupboards and beds and the backs of the doors.

Very Private? and Linder: A Dream Between Sleeping and Waking are both on show at Charleston in Sussex until March 12, 2023.