From Dalí’s Mae West sofa to cutting-edge chairs pulled out of thin air, the Design Museum show traces the movement’s impact on design – here, curator Kathryn Johnson takes us through the highlights

From its origins in the early 1920s, the surrealist movement rose “out of the ashes of Dada” to represent artists who dissented from the decades of rationalism that came before them. Veering away from contemporary notions of reality, they embraced the element of surprise, impracticality, paradox, and fantasy. It’s this revolutionary anti-logic that ties together some of the most iconic works from the movement’s height in the first half of the 20th century, and continues to define the artworks we recognise as surrealist to this day.

Given the surrealist obsession with the fantastical and the absurd, it’s not surprising that the movement has often been considered (and criticised) as a faction of the art world that is uniquely divorced from our lived realities. But this is a misconception. As explored in a new exhibition, surrealism also had a groundbreaking impact on design – from fashion to furniture and film – that took it out of the dream world and back into everyday life.

Just opened at London’s Design Museum, Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today brings together work by a range of surrealist pioneers and their descendants, from Dalí, Magritte, Man Ray, and Leonora Carrington, to Sarah Lucas, Tim Walker, Iris van Herpen and AnOther’s current cover star, Björk. Spanning almost 100 years, the objects on show – most of which are on loan from Germany’s Vitra Design Museum – include iconic sculptures and readymades, such as Marcel Duchamp’s Porte-Bouteilles (1959), alongside prime examples of surrealist fashion and interior design, and technological innovations that symbolise an emerging relationship between surrealism and AI.

Below, Kathryn Johnson, curator of the Objects of Desire exhibition at the Design Museum, talks us through some of the highlights.

Salvador Dalí, Edward James, Lobster Telephone (1938)

This is one of the exhibition’s most iconic works and is key in illustrating how the early surrealist practice of collaging together everyday objects into surprising hybrids led to innovative works of design. Dalí designed it for the home of British art collector Edward James, and it has been loaned to the Design Museum by the Edward James Foundation at West Dean College. It is a fully functioning telephone, designed to give the impression that its user is kissing the lobster when speaking into the receiver. Dalí saw both lobsters and telephones as erotic objects, and his first designs for this object were titled the “Aphrodisiac Telephone”.

James commissioned eleven Lobster Telephones for his London townhouse, and worked closely with Dalí on the final choice of red and black and all-white colourways. The piece is often shown in isolation as an art sculpture, but in the Objects of Desire exhibition you can see it next to a Mae West Lips sofa and Champagne Glass lamp – also designed by Dalí in close collaboration with James. The display evokes James’ wild and flamboyant interiors, as well as paying tribute to his important role in the making of this piece.

Meret Oppenheim, Bracelet en fourrure (2014 edition of 1935 original)

Meret Oppenheim designed a fur-covered bracelet for Elsa Schiaparelli and reportedly wore the prototype whilst meeting with fellow artists Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar at a Parisian café. They played with the idea that anything might be covered in fur, and Oppenheim soon afterwards created her widely celebrated surrealist work Luncheon in Fur / Object – a fur-covered cup and saucer, which disrupts expectations by combining the domestic with the uncanny. This piece is a contemporary edition of her design made by Gems and Ladders.

It's interesting to compare this piece with a work like Dali’s Mae West Lips sofa, which plays to a commercialised stereotype of female sexuality – passive, luscious, available. Oppenheim’s use of fur is no less erotic, but her bracelet has a feral, savage edge, which empowers the woman wearing it. The critical role that women played in surrealism is getting long overdue recognition now. We’ve taken the opportunity in Objects of Desire to pair works by Oppenheim and other seminal figures – Leonora Carrington, Claude Cahun, Leonor Fini among them – with other more contemporary female artists and designers, from Cinzia Ruggeri to Wieki Somers, Sarah Lucas and Najla el Zein.

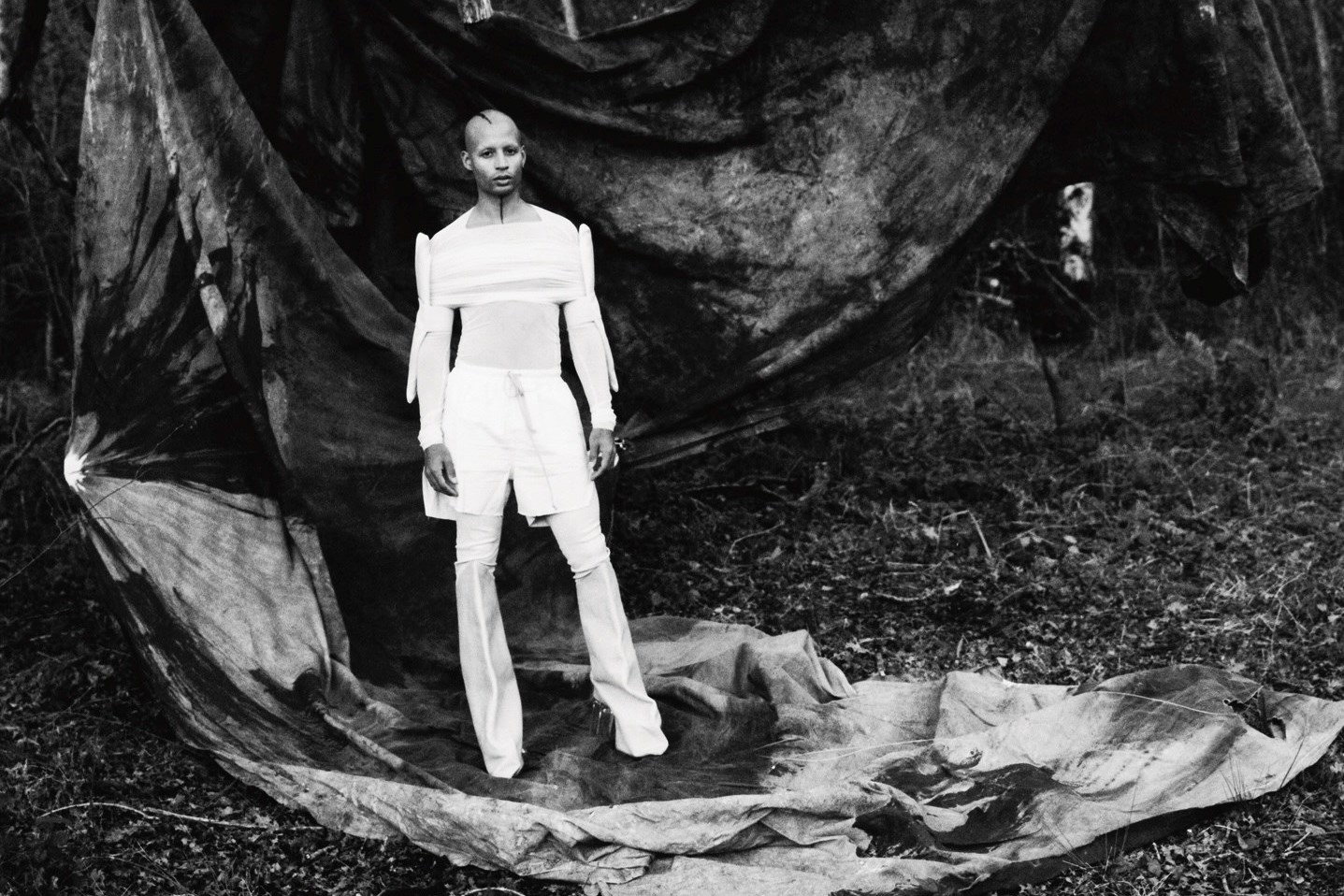

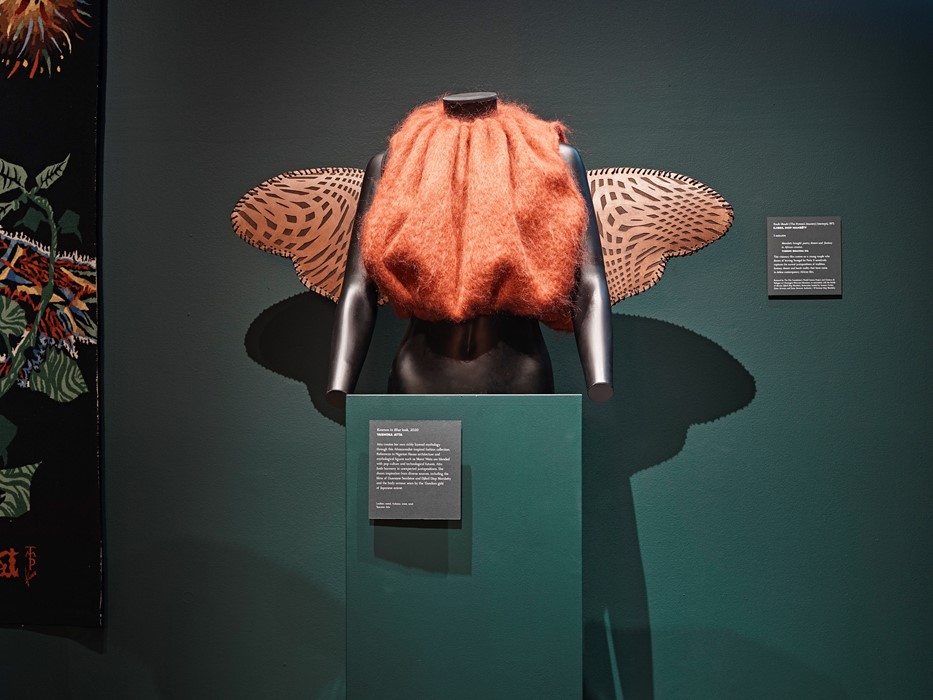

Yasmina Atta, Look from Kosmos in Blue collection (2020)

Fashion designer Yasmina Atta creates her own richly-layered mythology through her Afrosurrealist-inspired graduate collection Kosmos in Blue. References to Nigerian Hausa architecture and mythological figures such as Mami Wata are blended with pop culture and technological futures. Atta finds harmony in unexpected juxtapositions and draws inspiration from diverse sources including the films of Ousmane Sembène and Djibril Diop Mambéty, and the body armour worn by the “Gundam girls” of Japanese anime.

This piece is a set of embellished leather wings, attached to the wearer’s body by a foam harness, under a soft, woollen vest. It has an intentionally DIY-feel, as it was made in Atta’s studio over lockdown when her access to materials was scarce. She wanted the final product to reflect this experience, and as a result the wings represent a more personal and ready-made brand of couture. If you’re lucky, you might catch the wings flapping in the Objects of Desire exhibition – they are attached to an Arduino mechanism. Nearby, you can see an excerpt from Mambéty’s visionary film Touki Bouki – a key inspiration for Atta – which centres on a young couple who dream of leaving Senegal for Paris, and sensitively captures the surreal juxtapositions of tradition, fantasy, dream and harsh reality that have come to define contemporary African film.

Schiaparelli by Daniel Roseberry, Pink minidress, Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2021

Elsa Schiaparelli described her signature pink as: “A shocking colour, pure and undiluted.” The muscular shape of this shocking pink minidress is Daniel Roseberry’s contemporary take on Schiaparelli’s design language. Maison Schiaparelli has been reborn this century and is currently moving forward in such exciting directions under Roseberry’s influence. We were thrilled to be able to display this minidress, accessorised with an oversized pair of brass earrings in the shape of the Maison Schiaparelli signature padlock, and a pair of boots with gold-coloured defined toes, echoing René Magritte’s painting Le Modele Rouge.

Man Ray, Cadeau (1963 replica of lost 1921 original)

One of the first works you see in the show is called Cadeau or Gift by Man Ray. The story goes that Man Ray was on his way to an exhibition in 1921 and needed to make a piece on the hoof to show. He went into an ironmonger and bought a flat iron and some nails, before proceeding to stick the nails to the flat iron with glue. Not only does it make the iron completely dysfunctional, it also has this aggressive, proto-punk edge. Instead of being a domestic tool for pressing clothes neatly, it becomes a weapon that could rip your clothes. Ripped and torn fabrics were introduced into fashion by Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí later on, well before they became a feature of punk fashion in the ’70s and ’80s.

Like some other “readymades” in the exhibition, including Duchamp’s iconic Porte-Bouteilles, this piece is a signed re-edition – which means that Man Ray recreated the work decades later as an authorised replica. The simple fact is that the original piece was a throwaway, radical gesture – so much so that it was literally thrown away, or lost, by the time it became famous through photographs and anecdotes. So, a curator’s plea to all rule-breaking artists and emerging or post-surrealists out there – keep your stuff safe!!

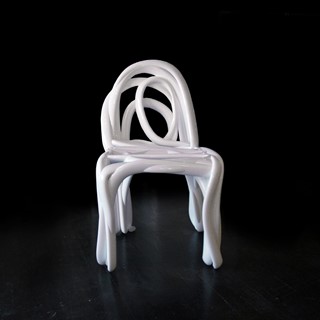

Front Studio, Sketch Furniture, AP 2 (2013)

Front Studio’s Sketch Chair is designed by literally sketching in mid-air with hand gestures. These gestures are captured using motion capture technology, then translated into 3D-printed works. The 3D form captures the original spontaneity and messiness of human movement in a functional piece of furniture. It connects wonderfully with Picasso’s light drawings, shown in a photograph beside the Sketch Chair in the exhibition.

Melting, fragmented and sprawling forms like that of the Sketch chair are central to surrealist design aesthetics. They express creative and psychological freedom. They look to natural forms and capitalise on chance accidents. Front Studio’s method of channelling physical, instinctive, movements is a great example of the way contemporary designers are still following the surrealists’ lead in looking for ways to bypass the rational mind, allow the subconscious to find expression and free themselves from conventional art and design practice.

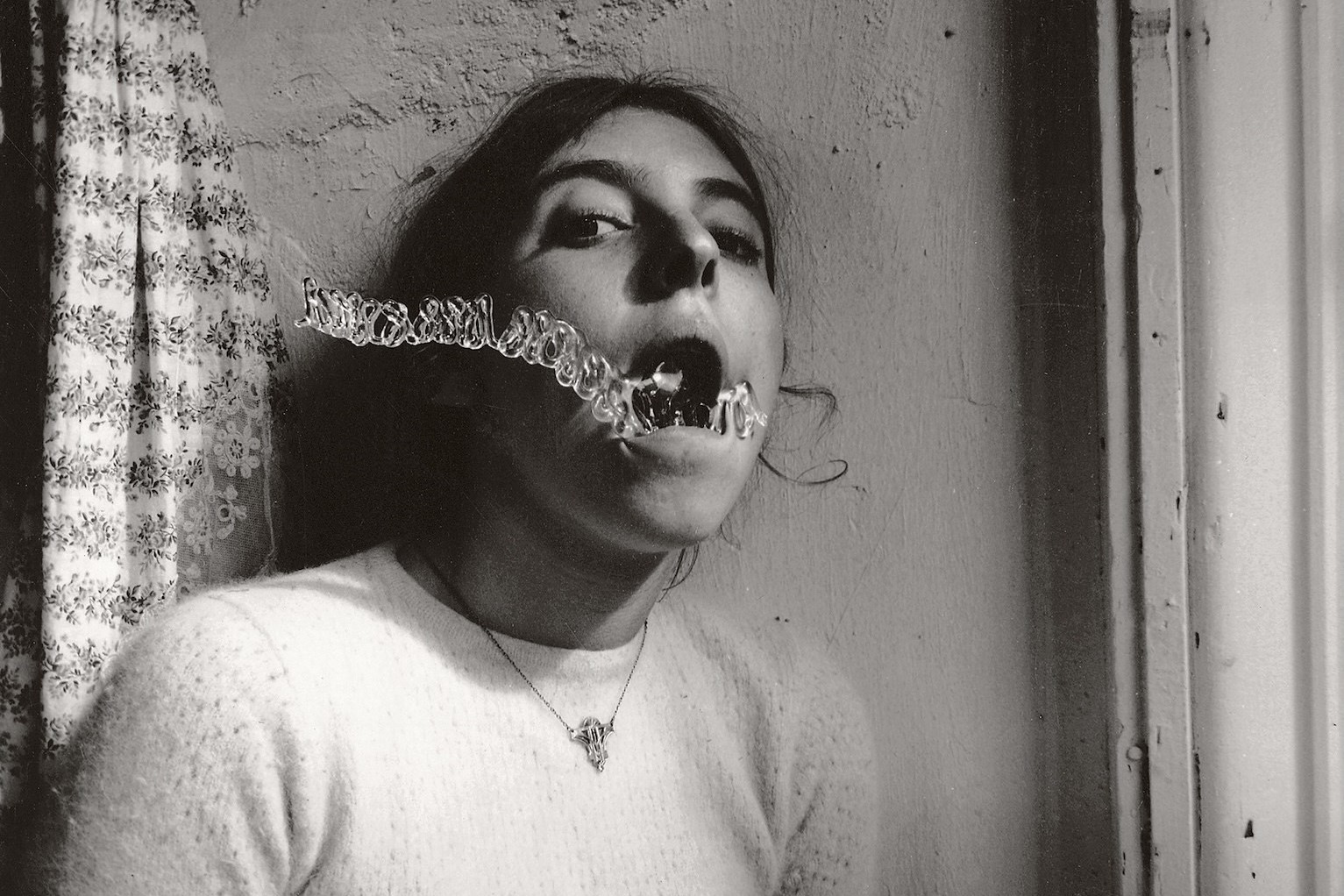

Tim Walker, Photographs from Stranger Than Paradise for W magazine (2013)

Famed fashion photographer Tim Walker has said that he always felt at home with, and inspired by, the surrealists. Both photographs in the exhibition feature Tilda Swinton as a model and collaborator and are from a shoot for W magazine titled Stranger than Paradise. Swinton also cites surrealist art as a major influence, describing it as a powerful thing to encounter as a teenager and “two thumbs up to the power of your imagination”. Walker and Swinton went to Mexico to Las Pozas, an incredible architectural folly created by Edward James – the man who also commissioned Dalí to design the Lobster Telephone and Mae West Lips sofa. They used the place as the set for a fashion shoot inspired by surrealist artists, referencing painters like Leonora Carrington and Leonor Fini.

We were very excited to be able to show these fantastic photos alongside intriguing and mysterious paintings by Carrington and Fini, courtesy of the Sainsbury Centre and West Dean College. Walker’s photography also features jewellery by Vicki Beamon, specifically, encrusted lips reminiscent of Dalí jewellery, making the images a dynamic fusion of surrealism’s past and present.

Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today is at the Design Museum in London until February 19, 2023.