As a new exhibition brings together the radical works of Linder and Hannah Wilke, we reflect on their art which questions women’s sexuality, domesticity and commodification

Women’s bodies are deeply politicised, whether they are used for porn, procreation, or domestic service. Radical feminist artists Hannah Wilke (b. 1940, d. 1993) and Linder (b. 1954) have both railed against the ways in which women are viewed by society and constrained by its rules. Now, the two artists are being brought together for the first time in a potent exhibition at Alison Jacques in London.

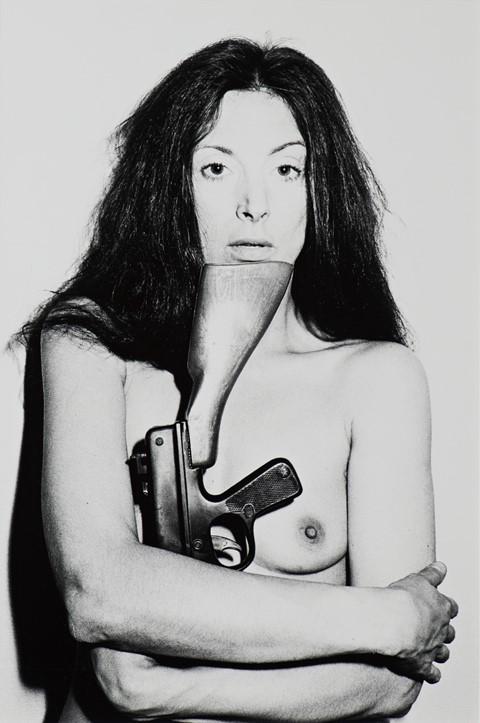

While Wilke and Linder began practicing in markedly different locations and time periods, there are undeniable parallels between their works and pioneering agendas. Wilke responded to the domestic constraints of 1950s life in the United States. She often referenced the misogynistic advertising imagery and slogans that accompanied and upheld these restrictive ideals. Wilke had a revolutionary approach to art making, creating work that was shocking not only within wider culture at the time, but also within the art world. Her images often featured her own naked body and she is known for a series of photographs in which she placed small replicas of vulvas across her face and nude form.

“Hannah Wilke was a very beautiful woman and she was criticised for using her own body,” says Martin Coppell from Alison Jacques. “It was as though she couldn’t be valued because she was a pretty woman. Instead of hiding behind her work she took her body and looks and put them directly in the centre.”

Where Wilke responded to the domestic shackles of the 1950s, Linder has famously explored the sexualisation of women’s bodies through porn and advertising for escort services. Her photomontages often depict nude bodies and faces roughly ripped through, cut and paste in a rebellious manner that also connects with her punk and New Romantic roots. Alongside her artistic practice, Linder was part of Manchester post-punk band Ludus and she is also a poet.

“I think Hannah Wilke fought really hard with her work,” says Coppell. “Some of that was already established for Linder because she was working in a later generation. But equally, I think the values of the New Romantics and punk scene were similar to the hippy feminist movement that Wilke was a part of. The cores that connect the two artists are feminism and bringing down the patriarchy. That crosses generations and boundaries.”

Both Wilke and Linder were also responding to societal change fueled by political upheaval. For Wilke, women’s pressure to be homemakers and child rearers was rooted in the chaos created by the First World War. This turbulence had in fact afforded many women greater freedoms while they were able to step into roles typically occupied by men. The United States in the 1950s was undergoing a huge drive to recover a sense of secure domestic life which had been so quickly pulled apart by the conflict. Linder railed against cataclysmic social and political turbulence in the United Kingdom, caused by Margaret Thatcher’s aggressively conservative government in the 1970s and 80s. Coming from Liverpool, the impact of Thatcher’s policies was deeply felt in her home city in the early years of Linder’s practice.

While the two artists never had a creative relationship, Hannah Wilke has been an enduring influence for Linder. In placing these two artists side by side, Alison Jacques highlights the ongoing drive for women’s freedoms through the generations. While each responded to the their specific times, they both had a clear desire to dismantle the patriarchal structures that keep those living within them boxed in in different ways.

“It’s this sense of reclaiming their bodies, which other people wanted to appropriate for their own means, whether that’s for pleasure or consumerist desires,” says Coppell. “That’s where the core of this show comes from.”

Linder | Hannah Wilke is on show Alison Jacques in London until 11 March 2023.