The American artist’s first new series in three years, now on show in Zurich, addresses the splintered and superficial parts of ourselves we choose to display on social media

It was the French philosopher Marquis de Sade who observed that “beauty belongs to the sphere of the simple, the ordinary, whilst ugliness is something extraordinary.” As the eponym suggests, Sade knew a thing or two about the complex allure of the unsightly. US artist Cindy Sherman does too. For decades, she has utilised the same rubbernecking power of the grotesque in her images, though it should be noted, that is where comparisons between her and the notorious libertine Sade end. In series like Disaster (1985) and Sex Pictures (1993), the grotesque becomes a source of fascination, a gravitational pull that is impossible to resist. Now, for her first new work in three years, presented at Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Sherman is enticing our morbid gaze once more.

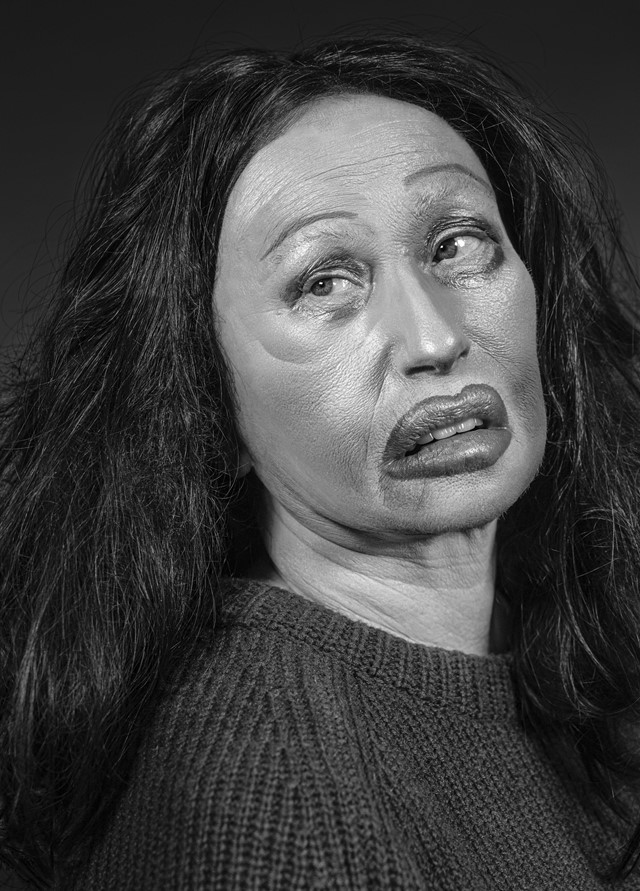

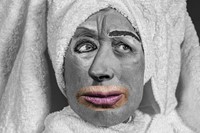

Unlike the aforementioned series, this new body of work sees the artist return as the subject of each image, though she would never consider them self-portraits. Sherman has always performed as someone other than herself, often with the help of make-up, costume, wigs and prosthetics. Here she has combined them all with a form of digital surgery, cutting her facial features from separate photographs before collaging them together to form maniacal, fragmented expressions.

From this process of construction, destruction and reconstruction arise Cronenbergian mutations: young and old, monochrome and colour, all crudely hewn together with jarring effect. This is, of course, entirely intentional. Sherman has priors for creating provocative imagery in which the mechanics of her altered appearance are left deliberately exposed. In a series like History Portraits (1988), the clear use of prosthetics is used to parody the voyeurism of historically revered male painters, while in her latest series, Sherman appears to take aim at something more contemporary.

The composite nature of each image is in one sense a reflection of the splintered and superficial parts of ourselves we choose to display on social media. Though they appear as self-portraits, by splicing together different photographs, the ‘sitter’ is technically absent from each work. Like the Ship of Theseus, Sherman uses the technique to question whether a face that has had all its original features replaced remains the same face, or even a face at all. In doing so, Sherman not only probes the border between reality and artifice, but highlights the laboured ways in which representations of the self are clearly constructed and pieced together.

In a related sense, these works reflect the inherent unreliability of images – hardly a new concern in photography, but here Sherman appears to specifically address the zeitgeist around the growing ubiquity of airbrushing, face-tuning apps and de-ageing filters. Artificial intelligence played no direct role in the making of the works, but given recent advances in the field, its spectre looms over them. In extracts from Sherman’s diary published in the exhibition’s catalogue, she makes note of how, “using face apps” (many of which utilise AI) directly influenced her use of Photoshop to create this series.

Given the 13 year timespan over which these photographs were taken, and the way the series as a whole addresses the Sherman’s own mortality, the question of ageing feels particularly relevant. By the artist’s own admission, the wrinkles and creases that she initially manipulated by pinching or squashing her skin required less effort with each passing year. The photographs present these ageing effects alongside attempts to conceal them: garish, blood-red lipstick, often violently applied, haphazardly drawn eyebrows and heavily caked powder. In an age where cosmetic procedures are more popular and accessible than ever, Sherman asks us: which is the true ugly?

Cindy Sherman is on show at Hauser & Wirth in Zurich until 16 September 2023. The accompanying exhibition catalogue is published by Hauser & Wirth and is out now.