Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters is a call to action. Exploring the lives and works of artists and writers whose practices speak from the body, Elkin weaves in her own experiences writing – first person – through Roe vs Wade, pandemic and pregnancy. Art Monsters is hard to describe because it feels new, yet when immersed in it, it’s entirely familiar (because I have a body, and you do too). Sensitising us to ways of saying the unsayable, Elkin surfaces the languages of queer bodies, sick bodies, racialised bodies, to confront the question: who claims the right to speak, and how?

‘Art Monster’ – a term first used by author Jenny Offill: “my plan was to never get married [but] be an art monster instead” – is employed by Elkin to characterise those who destabilise binary narratives of shame or empowerment, domesticity or art, neither catering to, nor downright rejecting. Art Monsters are deemed difficult: they engorge, exceed, overshare. But in (over)sharing experiences, they forge an ethical connection with each other.

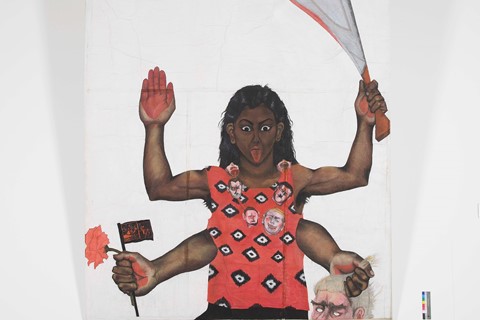

Through language, Elkin has constructed a feminist lineage across time and space, connecting Kathy Acker to Sutapa Biswas to Ana Mendieta. And just as language can build, Elkin reminds us, it can blow to pieces: “A Republic might be brought down by a poem.”

Below, we spoke to Lauren Elkin about the inspirations behind Art Monsters.

Isabelle Bucklow: How did this book come about?

Lauren Elkin: I’ve been interested in art for a really long time, particularly artists working across genres. They were not trying to develop theories of what they were doing, just trying to make work that spoke to them.

The book began in 2015 when my PhD advisor Jane Marcus died. Jane was a great [Virginia] Woolf scholar, and an incredible feminist activist. There was something excessive about her. She had a lot of anger and I was very impressed by that. When she died, I was bereft and wondered, how can I be worthy of Jane? I started thinking about Woolf's Three Guineas – connecting feminism, pacifism and socialism – a book EM Forster said ‘marred her work like a disease’. That got me thinking about excessive feminist, or monstrous, gestures.

IB: Hence Art Monsters. But what was it about this term that resonated with your intentions for the book?

LE: We first encountered ‘Art Monster’ in Dept of Speculation [by Jenny Offill]. She used it as if we all already knew it and, given the response, I guess we did. But then, I was like, now Jenny has given it to us and it’s entered the feminist lexicon, how will we use it?

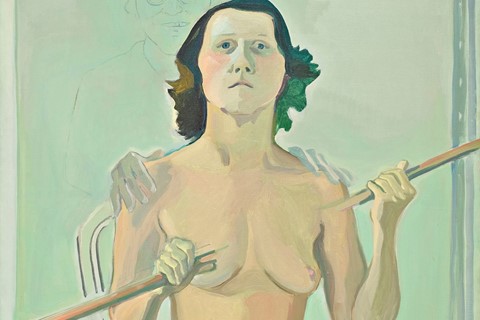

I’d seen a picture [Touching the Walls with Both Hands Simultaneously, 1975] by Rebecca Horne where she stands in a ballet studio with what look like talons extending from her hands that touch both walls. I was like, there! She’s an art monster! She’s using these monstrous appendages to say “I’m here, I can be bigger”. I started thinking of the art monster as someone who reclaims space for herself, or creates troubling works that make us think about our bodies.

IB: Thanks to Julia Kristeva, ‘the abject’ has become a constant in feminist histories of the body and, given your subtitle ‘unruly bodies in feminist art’, I suspected it would feature! But you stress “the abject is not the only correlative” to speak as a woman …

LE: I have a strong contrarian spirit! I don’t do things that seem obvious, and abjection, the feminine grotesque, seemed obvious. It seemed to me that this aesthetic of imperfection and ugliness is something feminists are already at home with, but there remains a suspicion about beauty.

[The artist] Hannah Wilke was so beautiful, she was trying to seduce the viewer. And back then, seduction was not a ‘serious feminist’ concern! She was only taken seriously by critics when [she was] sick and dying. Wilke’s work posed some kind of problem: the problem of beauty and art, their culture [in the 1970s] and our contemporary culture. The answer was not in the abject. Instead, I started looking at Carolee Schneeman, going through her writings, zines, performances and paintings. I just lost myself in her and realised that was the way forward.

IB: Schneeman really does feel like a guide through your book, and you acknowledge the significance of 1970s artists. What was so charged about that time?

LE: 1975 was like an annus mirabilis [a year of extremely good events]. All this amazing art came out then. People weren’t literally sitting around together – they were just thinking the same stuff at the same time. And something really important I was trying to think about in this book was connection and community. We’re not making art by ourselves. Even if, like me, you have a kid and feel very isolated a lot of the time, now you can share ideas and images on Twitter and Instagram. It’s important to acknowledge that feminist activism can include – I hope – writing a book alone, but connected, in your room.

“I started thinking of the art monster as someone who reclaims space for herself, or creates troubling works that make us think about our bodies” – Lauren Elkin

IB: The section on Dana Schutz looks at when the art monster goes too far – a sobering warning that art monsters can abuse excess.

LE: You know, ‘the monstrous’ – in Greek and Latin – has the joint etymologies of sign and warning. As I was writing, there were reckonings with Schutz’s controversial painting of Emmett Till’s murdered black body. It felt like monstrosity gone awry. It would be wrongheaded to boil the controversy down to whether artists can paint whatever they want, or not. Likewise, with the monstrous, I didn’t want it to be this gung-ho feminist singing the songs of badass women in order to sell more books. We can take risks and think we’re being monstrous, but the risk might prove really damaging. We need to think seriously about what art monster means and what we can do with it and figure out how we could do better. And I’m not exempt!

IB: You mention your difficulty with Kathy Acker. A brave move in a feminist book, as Acker is a bit of a hero! I appreciated this though, because I admit I also find reading her difficult ...

LE: Someone has to say it out loud! I don’t think that we talk about that enough. I kept putting this chapter off, but then I faced the fact I was never going to do this perfect accounting of Kathy Acker as a writer, so maybe I should make it about my response to her. We all love Kathy Acker, I love everything that she stands for, but then when you actually read her … like, oh man, really? It’s not like we just read her work seamlessly and it’s no problem. Actually, it’s really, really challenging. And like Hannah Wilke, she is purposefully challenging you and what you expect. They are both taking the piss.

IB: One of the ‘difficulties’ you mention is who Acker speaks from and towards. Why did you think it was important to go about disentangling Acker from her self-proclaimed masculinist lineage?

LE: She positioned her work within a really macho canon. Acker wanted to be taken seriously as a writer, she was deeply invested in theory and specifically in feminist theory, but she felt rejected by the feminists! She felt very rejected by how feminism defined itself at the time, the women’s movement specifically. Kathy Acker was a really interesting figure and I wanted to really think about what she was doing in her work that was so important that she ran the risk of being called a monster or being ostracised by ‘feminists’. Reckoning with her, with Blue Tape, I came to feel really fond of her. I wanted to defend her and make an argument for why we should read her. (OK, but maybe not all of her!)

IB: Many of the book’s protagonists work against or outside masculine literary structures. And you do too: eschewing linear chronology, fragmenting narrative flow, maintaining paradox. How did you go about disavowing the masculine sentence within the context of a mainstream publishing imprint?

LE: With [my 2016 book] Flâneuse, I was still under the influence of academic literary scholarship. But my next book [No. 91/92, 2021] was basically an unedited writing exercise from my phone notes. That allowed me to kind of shake off and do whatever on the page and eventually publish this. Art Monsters is not argument-driven, it’s more an exploration. Still, I step back and diagnose the thing: I couldn’t help having a section where I define monsters … there is some monster theory.

I’m very aware that I’m working with a corporate publisher, but when I was publishing in academia, I wasn’t satisfied writing for a very small community of people. I want to write for a broader public and have this conversation with as many people as are up for it. [With Art Monsters], you don’t have to read the whole thing in a linear way, you can dip in and out. Sure, it’s a tricky thing to be writing feminist criticism like this for a corporate publisher, for a mainstream public, but I’m trying to keep doing it.

Art Monsters by Lauren Elkin is published by Penguin and is out now.