Inspired largely by her father’s secret collection of porn magazines, Carla Williams’ frank self-portraits have been kept secret for more than 30 years – until now

Carla Williams was 18 when she started taking self-portraits. It was 1984 – the days of the darkroom, no digital. “I knew I wasn’t a proficient technician with 35 millimetre,” Williams explains. “I didn’t want to have to ask a sitter to work with me. So I thought, well, I can just do it myself.”

This audacity took Williams far; her practice of self-portraiture evolved and lasted 15 years, a period of time that chronicled her life as an undergraduate at Princeton and then later as a graduate student at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. No one else besides her and her fellow classmates ever laid eyes on them. “I didn’t share them with my family,” says Williams. “Certainly not with my friends outside of photo class. I was just really satisfied to make them.”

After some time, Williams put the camera down. “I stopped because I didn’t want to participate in the art world,” says Williams. “I just wasn’t interested. I didn’t enjoy it and I didn’t really imagine trying to make a career in a field I wasn’t enjoying. But all of that didn’t make me stop loving photography.” She edited photo journals and co-wrote the groundbreaking survey The Black Female Body: A Photographic History with Deborah Willis. In 2014, she moved to New Orleans and opened a store specialising in vintage material by Black artists. The photographs remained with Williams all the while, preserved in acid-free boxes and sleeves.

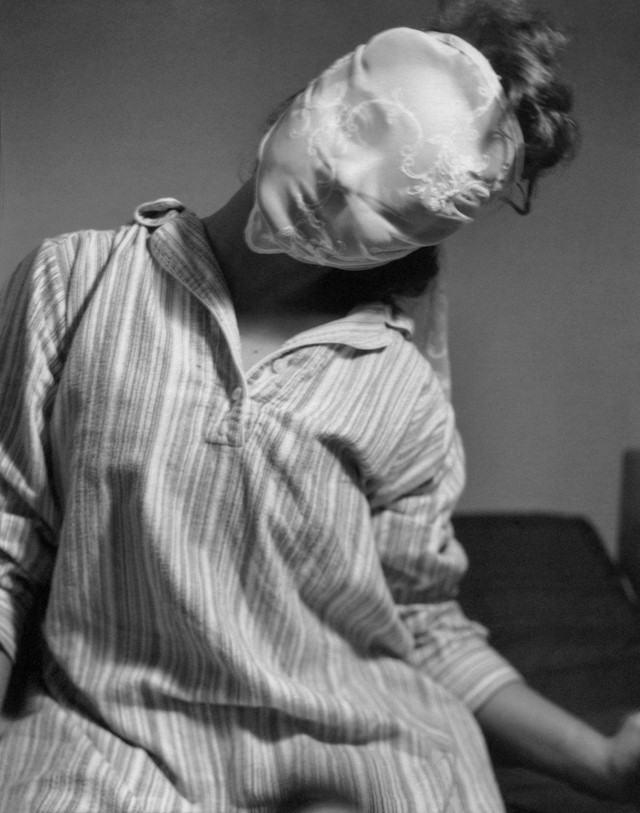

After more than 30 years, Williams’ thrilling self-portraits are now available for the first time in a monograph titled Tender, published by TBW Books. A love letter to the self, Tender chronicles a young woman becoming, interrogating, and making and unmaking herself again and again. As suggested by the title, Williams’ images also evoke a softness, a reversal of the word’s legal definition as something to be owned or exchanged. Her gaze is cheeky and frank, bracing yet playful, manned by a photo historian’s eye. Like her contemporaries Carrie Mae Weems and Pat Ward Williams, Williams used self-portraiture to insert herself into photographic history. She references and alludes to the racial spectres that haunt our visual imagination – the Jezebel, the Mammy, Hottentot Venus – while surpassing, if not altogether reinscribing them.

The blueprint for Williams has always been a perhaps unexpected source: the pornography stash she found as a youth, hidden in the bathroom under the sink, tucked between embroidered towels – her father’s. The availability of these images – pages of Playboy, Penthouse or the rare Hustler – “implied a false taboo, a peekaboo permission”.

“There’s this whole history of Black women in photography that I was never gonna learn in school,” says Williams. “They were never gonna bring those pictures in the classroom.” Williams’s fascination remains; she now collects vintage photographs of Black pinups from the 1940s to 1970s. “I think for so long I had this perception that it didn’t exist, but it hugely existed. It’s contemporaneous with Players and things we’re all familiar about but that mostly started in the 70s and onward. These are from decades earlier and it’s just amazing. I think of all of these women as my aunties.” In Tender too Williams plays pinup, framing herself with a cherished gaze, all longing turned inward. To live inside her images is to relish in the delight and playfulness the erotic offers.

Williams also cites photographers Doug and Mike Starn, Anne Noggle and Cindy Sherman as key influences. “The Starn twins, although my work looked nothing like theirs, emerged in the mid-80s and they were the first really successful photographers who broke through the frame,” says Williams. “They would make prints that they would tape and staple them together and make sculptural objects out them.” This lack of preciousness appealed to Williams, as did Noggle’s fearlessness and Sherman’s ability to “use the self-portrait to do a lot of different things over time and with different emphasis.”

The publication of Tender came as a surprise to Williams. When she closed her shop due to the Covid-19 pandemic, one of the first things she did was scan her photographs. She posted a few images on her Instagram story and thought little of it. On the strength of these images, photographer Paul Schiek reached out, asking if she’d be interested in publishing a book. Schiek then edited the images with intern Catherine Symens-Bucher. When Williams finally received the edit, she was “stunned”.

“It was perfection,” she says. “I didn’t change anything. Their edit, their sequencing, the whole of it. That was really one of the most profound moments because I didn’t know these people. This work was practically older than both of them, and they nailed it. They really got it. They had done just a perfect job with the editing and sequencing. I was blown away.”

Working on Tender has revived Williams’s practice. She has yet to photograph again, but has an exhibition with Higher Pictures planned for the fall. “For now, I am really focused on revisiting and putting out the work that already exists,” she says. “I’m not yet thinking about making anything again in part because I used to really love the dark room. I don’t really love digital. It’s practical for so many reasons, but so much of photography came out of just loving every aspect of it. The whole experience of the dark room is such a different animal. I’m kind of in that ‘we’ll see’ stage. But I’m definitely going to continue to actively collect. I can’t stop. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to stop. I really want those pictures to be out there so that it expands even more what we think of Black women’s representation and agency and just the whole complex history of us.”

Tender by Carla Williams is published by TBW Books, and is out now.