As her new show opens at Victoria Miro Venice, British painter Chantal Joffe talks about her surreal summer spent working in the Italian city, and why it felt like “learning to see again”

Contrary to the name of her new exhibition in Venice, there is no eel to be found in Chantal Joffe’s latest show, though she did buy one at the Rialto fish market and carry it back to her studio under the sweltering August sun (following in the footsteps of the photographer Francesca Woodman). Her attempts to paint the slippery creature failed; instead, she found herself capturing the process of living within the floating city in real time for The Eel, starting with the overwhelm she felt at the beginning of her residency at the Victoria Miro Gallery, to finishing just days before her exhibition’s installation when she didn’t want to stop.

Joffe, a highly acclaimed British artist, is known for layering oil paint to create beautifully composite landscapes from faces and bodies. Over the summer – the last before her daughter heads off to college – she painted colourful Venetian scenes that carry a sombre undercurrent. A mix of portraits and self-portraits track bodies around the city, collapsed on sun-loungers or upon the bare frame of a single studio bed, walking along the Zattere or perched on a vaporetto. As the writer Olivia Laing captures in her exhibition text, the fragments of the city swirl together. “How can you paint all this? Put your body in the middle of it and hope to catch a flash as something vanishes or changes state,” she writes. “Everything is gorgeous, everything contains its secret evidence of death.”

In the floating city before the exhibition opening, AnOther spoke to Chantal Joffe about beauty, light, and the importance of embarrassment.

Thea Hawlin: What was it like creating these works in Venice?

Chantal Joffe: At first I was a bit panic-stricken because I’d said I’d make the show in six weeks, so I just lay on the bed in the studio. I just painted how it felt to be here – my awareness of place is so heavy. It’s a big thing to work here, thinking about Bellini, Titian and Carpaccio; everybody is always dancing in your head, there’s this insane visual overload.

To live here was completely new, to hear the bells. When I arrived I was running quite fast just trying to understand where I was. There’s no way you can paint in Venice without painting about being in Venice. It’s been the most incredible place to paint because everything is new. It’s like learning to see again. Just being on the Lido, I was like “Oh my god – the light!” and with the ombrelloni you get these mad contrasts and the sand changes colour. I became obsessed, I felt a bit like when the impressionists got to the south of France. I’m not saying I’m like them, but my sense of light … I’m coming from London, where it’s never light.

TH: Barbara Hepworth said the same thing when she studied in Rome, it’s all about the light.

CJ: It bleaches things out, I had to scramble to get a palette, to paint it all, and I’m never achieving it but it’s the chase. I’ve never painted here, I’ve shown here but I’ve never worked here. You think, “Oh I’m just going to paint,” but Venice tells you what you can paint. The last two pictures I made got kind of infused with religiosity, I made my boyfriend a weird kind of saint, but it’s because you’re looking constantly at Titian and Veronese. You become drenched, but I kind of love that because you don’t leave the same person you arrived.

Everything here is different and as a painter that’s all you want – change and things to be new. These paintings are not like any other paintings I’ve made, they’re really weird … things just kept coming out of my hands in a way that I’m not used to.

TH: Did you have a clear concept for the show?

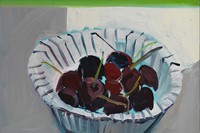

CJ: My first idea had been to paint still lifes to give me a kind of anchor. So I painted a sandwich and some cherries, and then after painting about six pictures of sandwiches and cannoli, I tried to paint the eel. I went to the fish market with Olivia [Laing] and Esme [her daughter], and when I went to buy the eel, the man asked, “How do you want it? I’m going to chop it up,” so then I said, “No, don’t chop it up because it’s to paint!” I was carrying this eel, scared of getting eel blood everywhere. Then there was the Freudian nightmare of it sliding into the sink in the studio, alive and slithery but heavy and dead and I was just screaming, I got a bin bag and it was like a dead body. It became this huge thing, like metamorphosis; I’m going to become the eel and wake up in a fish market and a woman will be buying me to paint. It became bigger and bigger in my head, and everywhere I went I thought “I’m the eel, I look like the eel,” but it also became a metaphor for Venice itself, this kind of beauty and horror. My daughter and I watched Death in Venice, and then she got really sick so we headed to A&E in a water taxi. It was a terrible moment but it was so beautiful.

TH: Was that beauty daunting at times?

CJ: How can you paint San Marco? At half seven it’s like a bowl of light. Somebody created a square to hold the sky – who does that? When you’re in the Doge’s Palace you’re looking at a picture of it during the plague but it’s the same. There’s a picture of me and my family from 1981 in front of San Marco visiting for the first time, the woven plastic chairs are the same. It’s heartbreaking, that sense of time in Venice. You can look at a painting of San Marco made 500 years ago and it’s the same.

TH: How do you engage with the intimacy of showing yourself as an artist?

CJ: It’s almost more interesting to reveal less, because of things like Instagram where people livestream events happening in their lives. Everyone wants to be seen, even in art everyone is telling you everything about their lives all the time and that’s a misunderstanding about what I’m trying to say. I want honesty and truth, but truth and honesty are not the same. There’s a terrible oversharing that can happen.

TH: Do you think that’s why painting can be so powerful? You can say so much more?

CJ: When you paint you talk to yourself and then suddenly it’s clear. It’s very much an act of understanding. If you’re making a painting about feeling, everyone’s reading it. It feels intensely revealing, but you have to keep risking embarrassment.

The Eel by Chantal Joffe is on show at Victoria Miro Venice until 21 October 2023.