As Tate Modern opens a new exhibition in London, we revisit our five-point guide to the late American artist’s work, which probed the dark underbelly of teenage American life

This article was originally published on 24 October 2023.

American artist Mike Kelley was a master of provocation, often bringing together found objects, film and performance to spine-chilling effect. He had a nuanced understanding of childhood and adolescence, probing the rituals and dark underbelly of teenage American life and repurposing over-loved stuffed toys.

Born in 1954 in Michigan, Kelley grew up in a Catholic working-class family. He was the youngest of four children, and his work is imbued with childhood memories and visceral depictions of collective trauma. He claimed that his unflinching practice was formed from a “shared culture of abuse”. His career took off in the 1980s, and while he achieved mainstream success, his irreverent work always kept him as something of an outsider.

The artist is now best recognised for his sardonic videos, as well as sculptures created from second-hand items sourced in flea markets, which often display the marks and scuffs of their previous lives. Tragically, Kelley died by suicide in 2012, at the age of 57. 11 years on, he is being celebrated with a major retrospective at Paris’ Bourse de Commerce, Ghost and Spirit, which will then travel to Tate Modern in London, K21 – Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

Below, we give you a five-point guide to Mike Kelley’s work.

1. Kelley created expansive, arduous video work

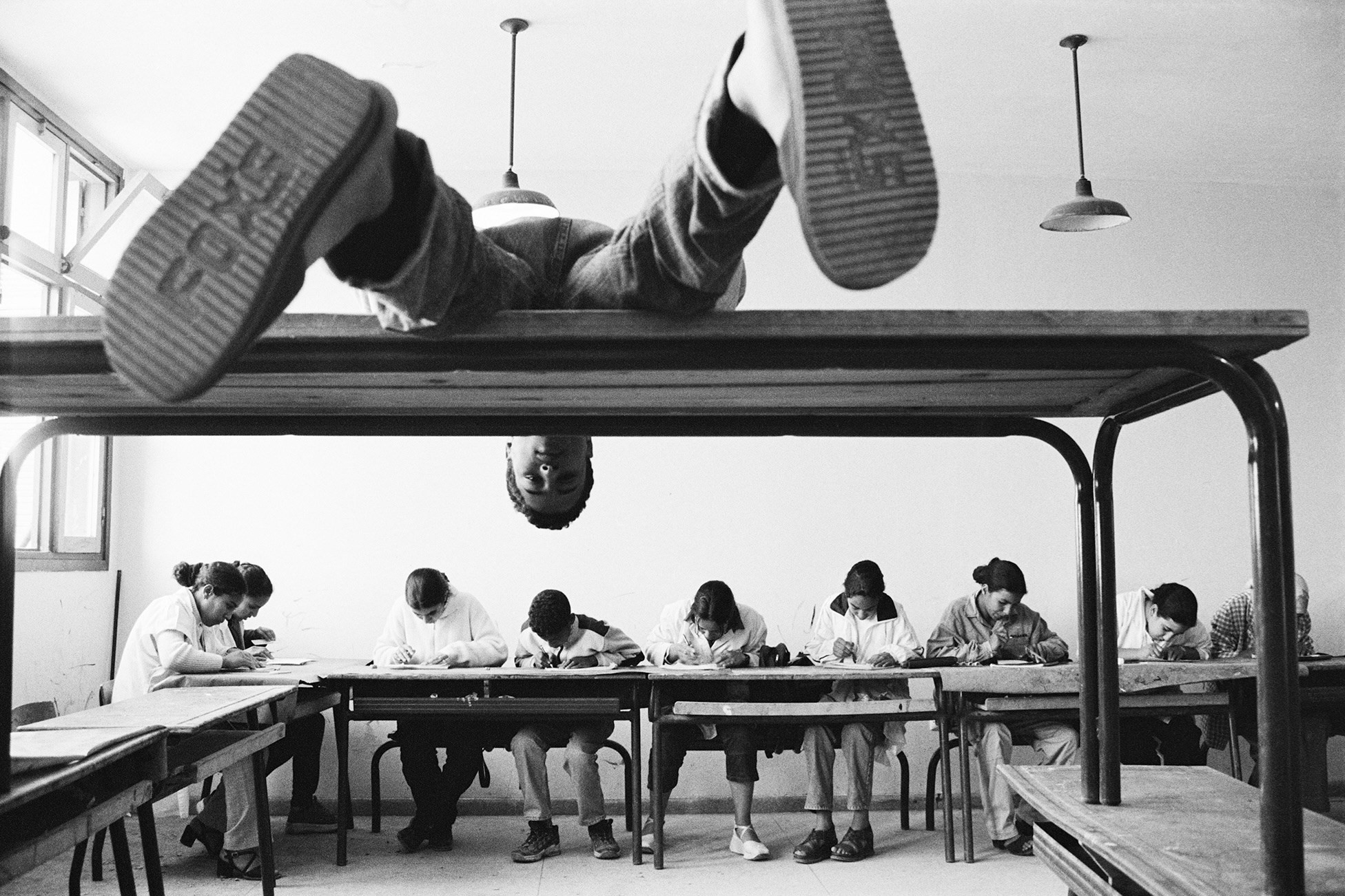

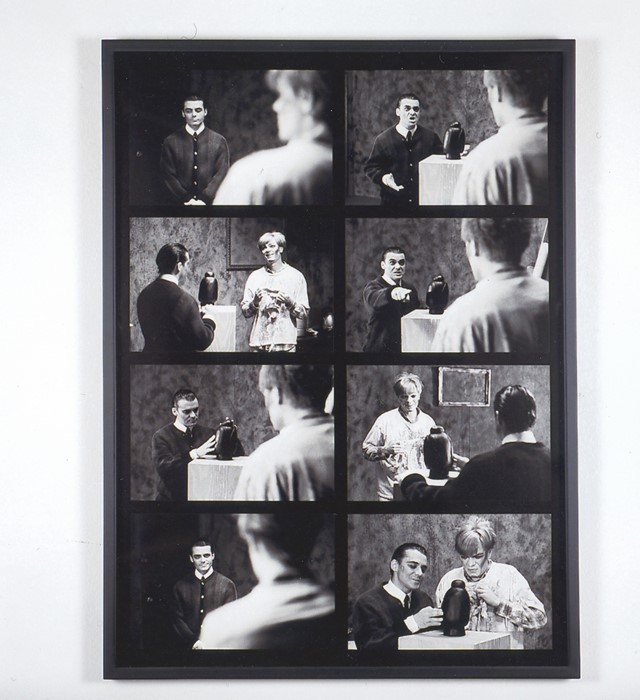

Kelley’s video work was tightly bound up with his performance practice. The Banana Man (1982) was his first video. Dressed in a yellow jumpsuit he performed the lead role, inspired by a rarely seen character on popular TV show Captain Kangaroo, who the artist heard about through his childhood friends but never actually saw on screen. His video questioned how multiple, disparate scenes can build the semblance of complete character. His later 2005 epic Day Is Done featured 25 video installations showing reconstructions of extracurricular activities, inspired by yearbook images of students in costume. This work connected with his 1995 installation Educational Complex, in which he reconstructed parts of his high school from memory, leaving unfinished the parts he could not remember. Like much of Kelley’s work, this related to the trauma of his youth and the human capacity to repress horror.

2. He is widely known for his work with stuffed toys

There is something undeniably creepy about a cuddly toy that has been loved to excess. Kelley’s repurposing of stuffed animals and dolls highlighted the wear and tear, both physical and emotional, that children experience as they grow up. He was drawn to handmade rather than standardised toys, as the psychology of the maker can be witnessed in their nuanced features. He also explored the way in which toys assert social gender norms and draw children into commercial desire from a young age. Kelley elevated toys to the position of high art, presenting them as highly loaded objects that can reflect important social, cultural and political issues.

3. His practice was deeply inspired by radical feminism

When Kelley graduated from the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in 1978, he was greatly inspired by the second-wave feminist artists of the time, many of whom utilised performance. He admired the way in which artists such as Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro employed cooperative elements in their work and their use of crafts typically seen as feminine or lower art forms to make powerful political statements. This impact can be witnessed in his arduous performance works – such as 1984’s The Sublime, which fused sadomasochistic elements with philosophical theories of the sublime – and textile assemblages – including More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid, 1987, which featured toys found in thrift stores and addressed the one-sided toil of parental love, questioning what might be expected in return.

4. He was interested in inconsistent memories of city architecture

Kelley was a huge comic book fan and one recurring series of works takes its cue from Superman’s birth city of Kandor. The 2005 to 2009 series Kandors Full Set features a selection of illuminated cities housed within hand-blown bottles. The works were based on 20 inconsistent comic book renderings of the city, exploring once more the unreliability of memory, this time in connection with Superman’s childhood. Kelley said that Kandor “functions as a constant reminder of Superman’s past” and “a metaphor for his alienated relationship to the planet he now occupies.” His cityscapes are both ghostly and playful, featuring small, colourful resin buildings – not unlike children’s gummy sweets – lit from below.

5. Kelley was a keen writer and originally wanted to be a novelist

When Kelley was a child, he wanted to be a novelist. His flair for weaving together narratives and exploring character psychology in depth can be felt throughout his artistic practice. Writing would prove to be a key component of his art and he frequently wrote creative essays with strong narrative voices. His writing explored psychoanalytically rooted ideas such as the uncanny and included searing takedowns of the mainstream art scene, once comparing the art world’s limited narrative of art history with Ronald Regan and George Bush’s control of the corporate media. In his 1999 paper Cross Gender / Cross Genre, the artist wrote, “I didn’t feel connected in any way to my family, to my country, or to reality for that matter: the world seemed to me a media facade, and all history a fiction – a pack of lies.”

Ghost and Spirit by Mike Kelley is on show at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris until 19 February 2024.