In 1976, the theorist Helene Cixous called upon women to reclaim their bodies, arguing for sensual pleasure as an expression of female and queer resistance to patriarchal power structures. She wrote: “We’ve been turned away from our bodies, shamefully taught to ignore them, to strike them with that stupid sexual modesty.”

In the spirit of Cixous, a multitude of photographers in 2023 shamelessly turned towards their own bodies, or those of friends, peers and lovers. But beyond the sexual or erotic, they embraced the corporeal to convey personal liberation, self-acceptance, or resist forms of oppression. In the post-Covid era, meditations on the body also become a metaphor for the yearning of physical closeness and genuine human connection in an increasingly disconnected world.

From Shae Detar’s use of the body as a tool for radical healing, to the pink and peach-hued photographs of Lean Lui’s girly gaze, or Benedict Brink’s textural shots revelling in the body as a form of still life, this year we have been reminded of the potent, provocative and poetic charge of the body in photography.

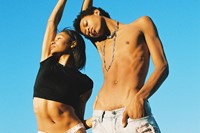

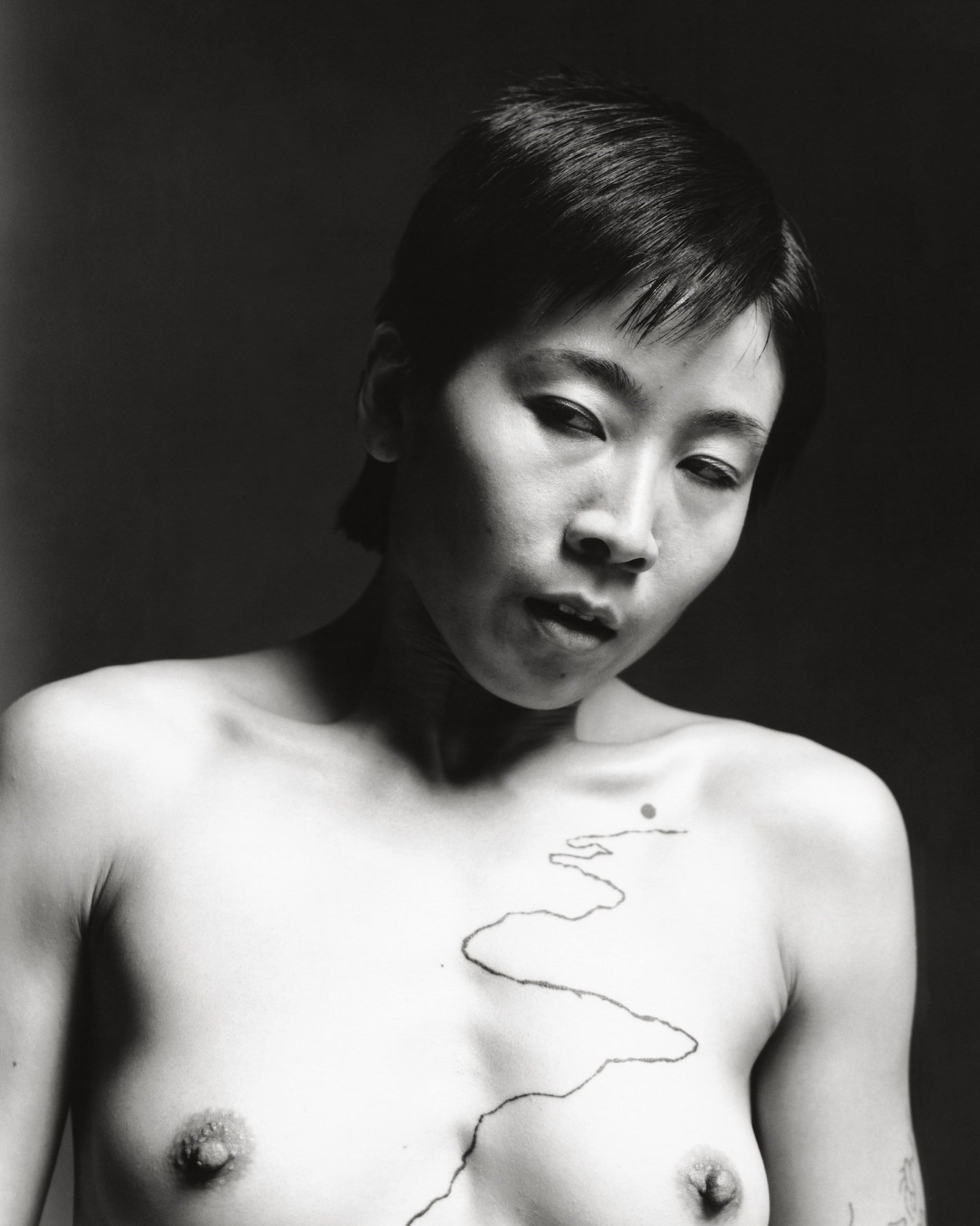

Lin Zhipeng (AKA No.223) at Saint Laurent, Rive Droite

The Beijing-based photographer Lin Zhipeng (also known as No.223) has been photographically documenting his closest friends for decades; something he plans to do until they all die as a way to chronicle evolving relationships across “the passage of time.” In collaboration with Saint Laurent and the label’s creative director Anthony Vaccarello, Zhipeng’s work was displayed in the brand’s Rive Droit concept stores in Paris and LA. Fascinated with the energetic and counterculture spirit of China’s youth, his work calls into question perceptions of the country’s conservativism, though his tender, erotic and often humorous work expands further afield, capturing friends and lovers in Tibet, Southeast Asia, Japan and Europe.

Read AnOther’s interview with Lin Zhipeng here.

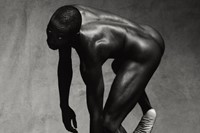

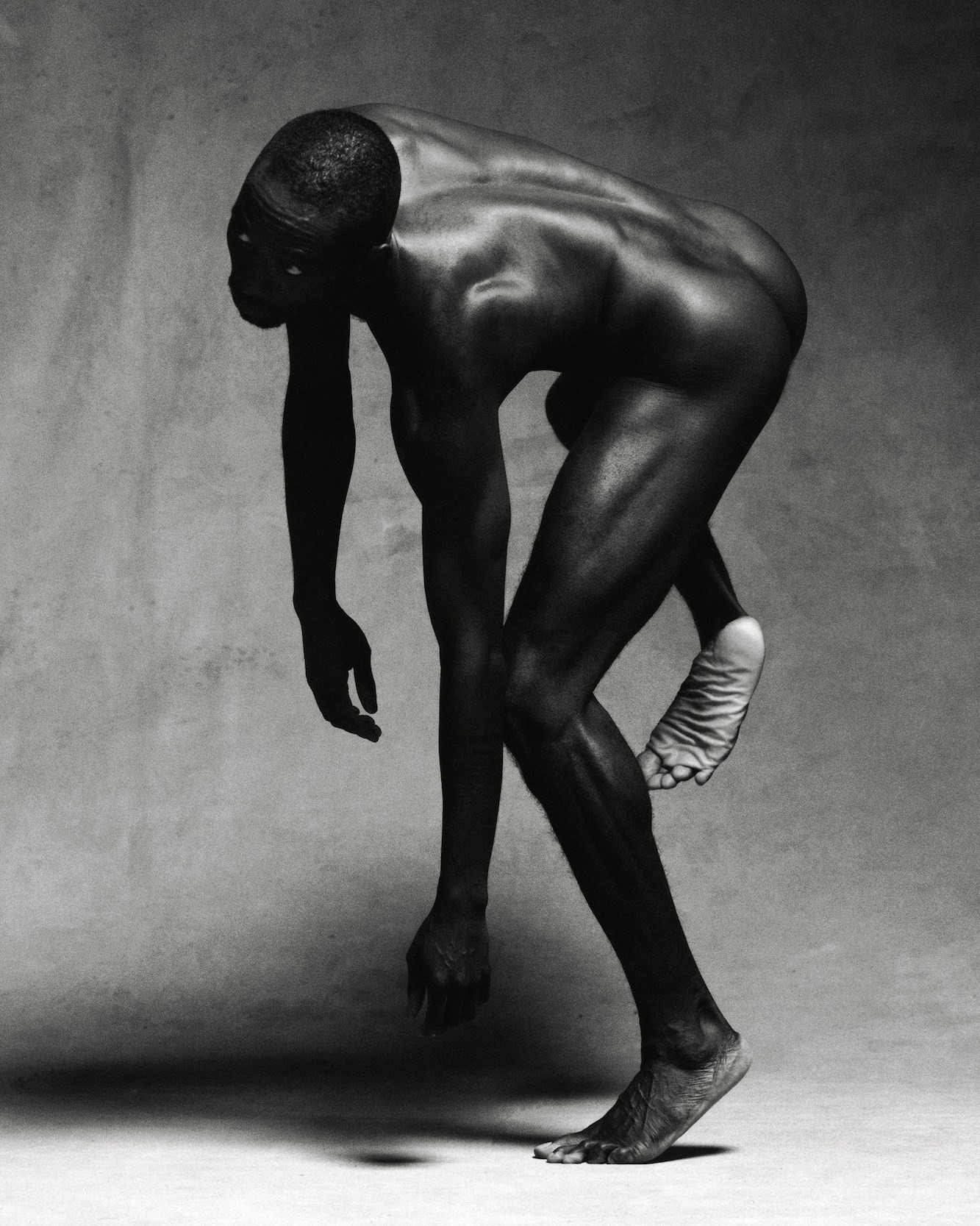

O by Luis Alberto Rodriguez

The Dominican-American photographer, Luis Alberto Rodriguez, published his book O earlier this year – a collection of high-contrast studio nudes in which bodies of all ages, shapes, and ethnicities, rhythmically choreograph themselves before the camera. Contorting, twisting, falling or leaping, Rodriguez’s meditation on the nude conveys sheer vulnerability. His fleshy body of work intends to “strip everything away”, thus removing the daily embellishments that conceal the body. Speaking to AnOther, he explained: “Nakedness just feels so completely generous … I really wanted rawness, so that people could connect to it in that very emotional way.”

Read AnOther’s interview with Luis Alberto Rodriguez here.

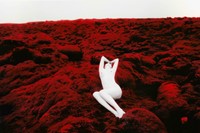

Another World by Shae Detar

Until her twenties, Shae Detar lived in an evangelical Christian cult. Aged 30, she turned to photography in an attempt to liberate herself from the religious strictures of her upbringing. Surreal and sensual, her resulting monograph, Another World, was released by Skeleton Key Press earlier this year, in which the female nude becomes a metaphor for the artist’s healing. “It’s literally me finding that freedom, meeting women, hearing their stories and seeing how confident they are,” she told AnOther. Her otherworldly shots – merging the painterly and photographic – present a fantastical world in which women transform into mystical, empowered beings, unencumbered by the male gaze.

Read AnOther’s interview with Shae Detar here.

Aseptic Field by Lean Lui

The year 2023 celebrated the conventional tropes of girlhood, exemplified by the hype of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and the ubiquity of the colour pink. Reminiscing on her own girlhood, the Hong Kong-born photographer Lean Lui released Aseptic Field. Her dreamy photographic gaze isolates the colours and textures of traditional femininity: soft pinks, peaches, pearls and petals. Saccharinely sweet but with a darker edge, Lui alludes to the slippery transition between adolescence and womanhood, as well as the contradictory perceptions of the female body: pure and innocent yet sexual and dangerously seductive. The claustrophobic world she captures illustrates her interiority; in which girlhood is shrouded by delicate artifice.

Read AnOther’s interview with Lean Lui here.

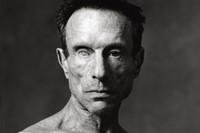

Ring Light New Testament by Peter De Potter

The erotically-charged monograph Ring Light New Testament by the Belgian photographer Peter de Potter was released earlier this summer, marking his fifth photo book since he came to prominence in the early 2000s. Obsessed with observing our online culture of sharing (or oversharing), de Potter’s latest body of work investigates how platforms such as TikTok or OnlyFans thwart our self-perception. Whether illustrative of narcissism or the pursuit of human connection, he questions our bodily behaviours online. “Everybody wants to be seen,” he says. “Sometimes literally, sometimes more on a metaphorical level – but to be seen, to be noticed by millions, or by one person, I think it’s a driving lifeforce.”

Read AnOther’s interview with Peter de Potter here.

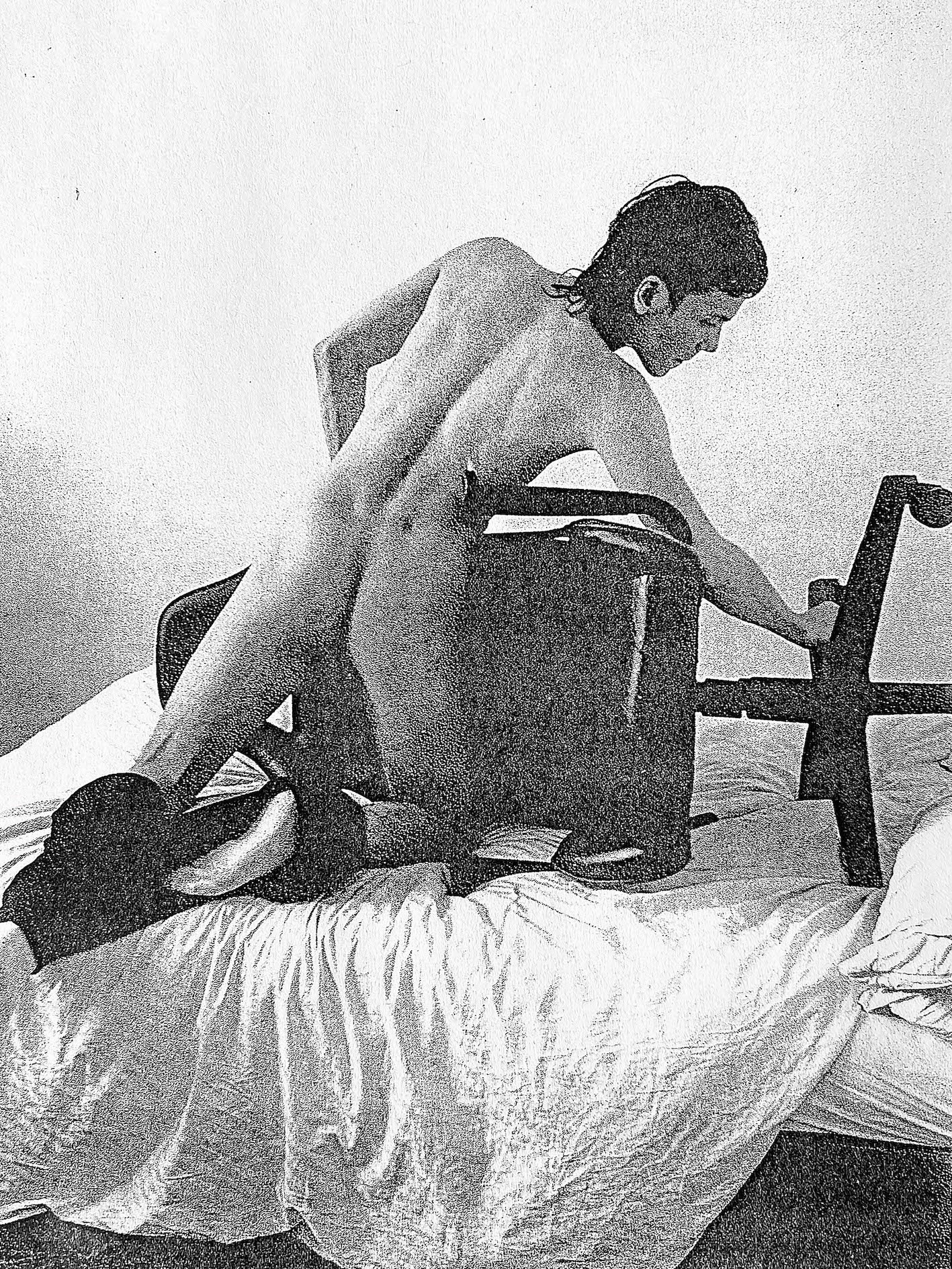

Tender by Carla Williams

When Carla Williams found her dad’s stash of porn magazines in the 1980s, it unleashed a latent fascination with the body. Shortly after, she took up a Polaroid 35mm camera to develop her own series of self-portraits. Published by TBW Books 30 years later, her corporeal interest resulted in the monograph Tender, assembling seductive self-portraits taken in private between 1984 and 1999. Chronicling her body on the cusp of adulthood, she delighted in the taboo playfulness of the erotic. The discovery of a shadowy world of sexual imagery propelled her towards an intimate dialogue with herself, as she grappled with her own, burgeoning queer sexuality.

Read AnOther’s interview with Carla Williams here.

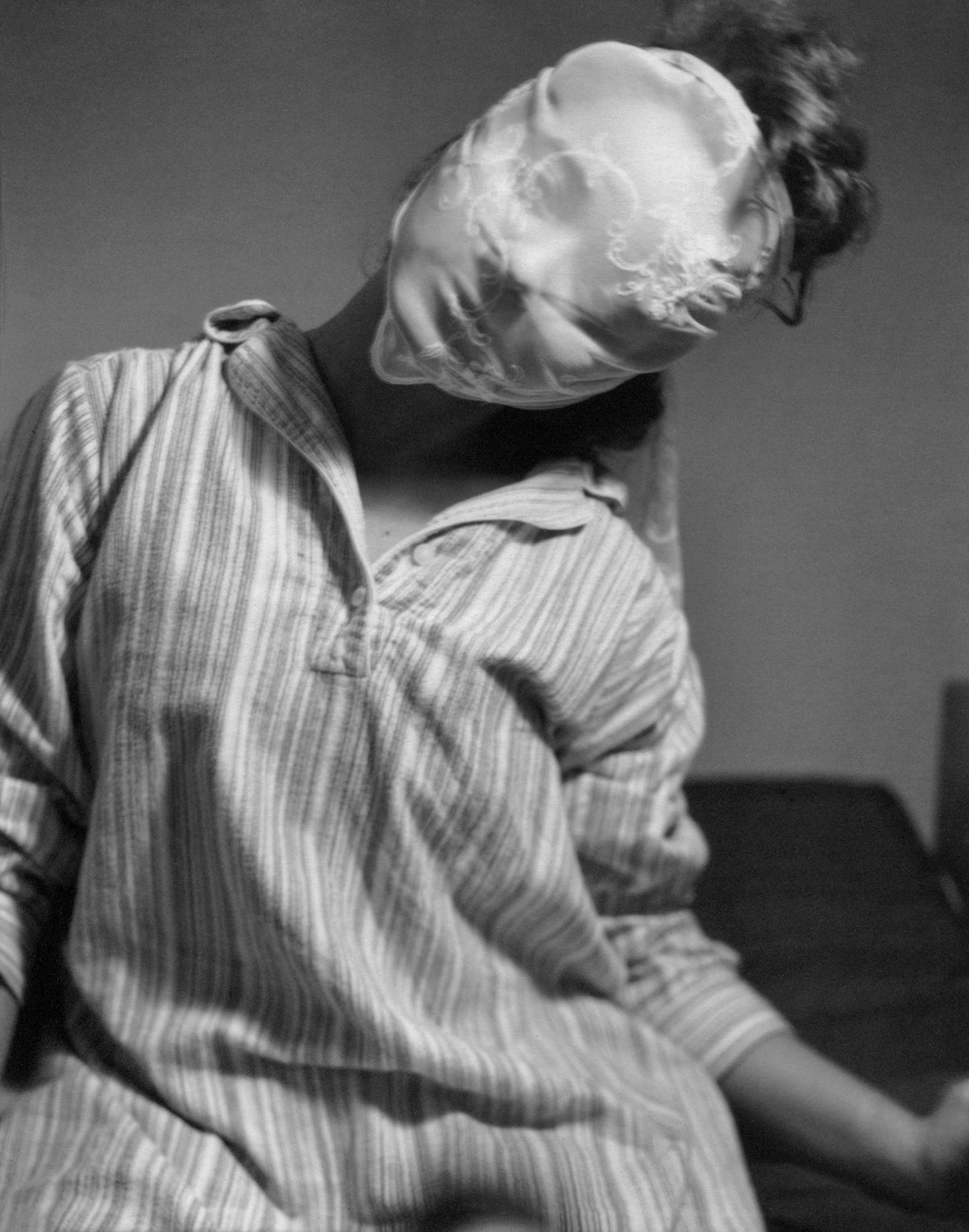

Love Me Again by Michella Bredahl

The tender photographs of the Danish filmmaker Michella Bredahl unveiled in Love Me Again present poignant moments between friends, lovers, mothers and children. Her work divests the male gaze as she captures women in quiet, interior spaces, conveying their unique energy as they recline on carpets, unmade beds, or vintage furnishings. Bredahl’s poetic gaze softly subverts the male tradition of painting (and sexualising) the reclining, female body: “I make my own mark on the poses I see being portrayed by men through the history of images,” she says.

Read AnOther’s interview with Michella Bredahl here.

The Year of the Dragon Calendar 2024 by Alexandra Leese

Year of the Dragon in 2024 is a photographic project that irreverently responds to the history of the erotic, nude calendar. Created by photographer Alexandra Leese and creative director Nellie Eden, the pair invited 13 Asian women from different cultures honouring the lunisolar zodiac to be photographed. “I wanted to create a project that felt like a celebration of culture, beauty and the power of women’s sexuality in a joyful way,” Leese told AnOther. Playful and subtly subversive, Leese displays sensitivity to each woman’s unique desires and sexualities, seeking to empower – rather than crudely objectify – their bodies through the female photographic gaze.

Read AnOther’s interview with Alexandra Leese here.

Corporeal by Spyros Rennt

What is a genuinely sexy image? This question underpins Corporeal, the third photo book by Greek photographer Spyros Rennt. Delving into the world of raves and nightclubs, Rennt captures the heady intimacy of dancing in the dark as well as the entwinement of nude bodies. Fleshy, raw and autobiographical, Rennt, who was once an avid clubber, found inspiration from another queer photographer, Wolfgang Tillmans. His unflinching photobook chronicles the hedonistic yearning for bodily connection amongst queer communities in cities, from Athens to Berlin. Speaking to AnOther, he remarked: “My work is personal but the experience is always universal.”

Read AnOther’s interview with Spyros Rennt here.

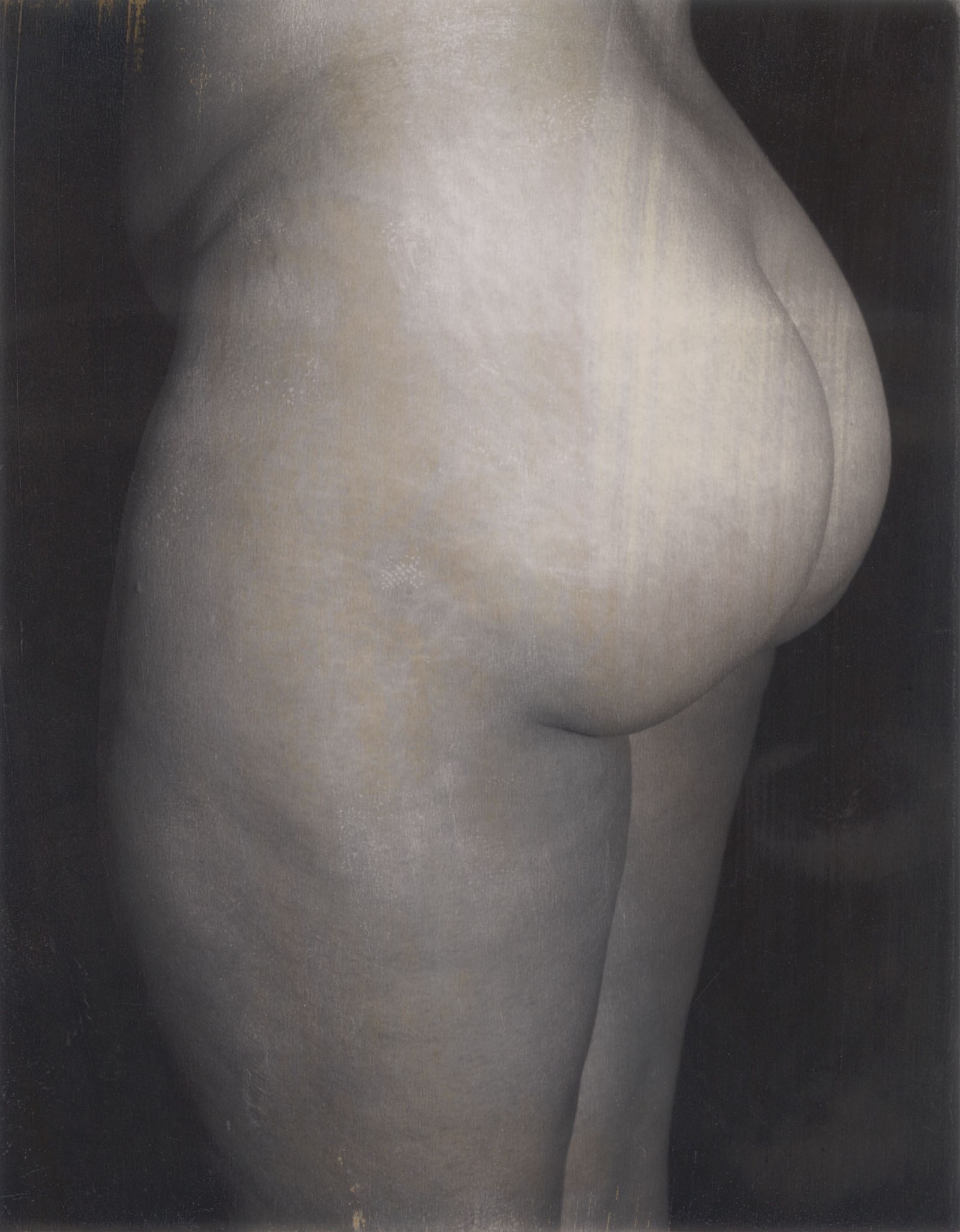

Look, Touch by Benedict Brink

Look, Touch, by the Australian photographer Benedict Brink, meditates on the vulnerability of the human body in its flawed and imperfect guises. Reflecting the relationship between the camera and the body, the gaze and embodied experience, Brink’s work operates beyond documentary practice – offering something sensual and tactile rather than cerebral. “I look at people and at bodies – it can become very nuanced and overly thought about. I wanted to bring it back to what it actually feels like to look and be looked at.” By isolating body parts, bathed in soft light, his artfully composed shots evoke the sensuality of painted still lifes.

Read AnOther’s interview with Benedict Brink here.