Founded by Ahmed Alramly, new digital publication Naima features contributions by artists including Rhea Dillon, Dozie Kanu and Frank Dorrey

Publisher and creative director Ahmed Alramly was fairly young when he first heard John Coltrane’s Naima. “It was the first time I’d encountered this Arabic name in this Black jazz context,” he explains. “I became so curious as to why this Black jazz musician from the States would title his song with an Arabic name.” Alramly would go on to discover the works of Yusef Lateef, Ahmad Jamal, and Art Blakey, jazz musicians who drew from Eastern mysticism. Years later, when it came time to come up with a name for his magazine, “Naima” immediately came to mind. “What I like about culture is finding these strange meeting points of two seemingly disparate places, and where they converge to birth something entirely new,” says Alramly. “A new look, a new style of music, a new subculture – that’s what Naima’s manifesto is all about, the convergence of contraries, and how so much of culture that I admire can be found there.”

Naima, whose first issue launched this month, is a new magazine of independent culture that aims to “give voice to certain movements in a space outside of where they are usually defined.” Naima will then publish digitally three times a year, culminating in a special edition anthology published in print. Each issue is divided into two sections, a particular theme and “Stories of Cultural Interest.”

Naima’s first issue explores the concept of “New Black Surrealism,” a term coined by Alramly that expands on WEB Du Bois’s concept of “double consciousness” – the dual perception of self that arises out of a sense of difference – and suggests “this double has multiplied.” “We live in a time where there’s cause for the advent of a triple, or quadruple, or perhaps best put, a multi-consciousness,” explains Alramly in his editor’s letter. “What is of vital interest is the additional layers of consciousness that have arrived with the passage of time, for the children of the second, third, or fourth generation, of whom there isn’t the imminent displacement from one to another, only the idea of another place, or the teachings and passings on through previous generations of ideals, myths, religions and sensibilities.” For Alramly, the idea of a multi-consciousness doesn’t just apply to those who identify as Black or as members of the African diaspora. “But the Black person facing the conflicting realities of the contemporary world, and dragging on in a perpetual state of non-belonging ultimately produces this new, unique form of existence – a surreal existence,” he concludes. Alramly defines this new independent movement in art as “New Black Surrealism.”

Alramly first arrived at the concept through his love of surrealist literature. “One of the things that drew me towards surrealism specifically was their fascination with the unknown,” says Alramly. “It was almost mystical, even though they were tipped towards the subconscious more so than the soul. It’s as if they’re looking for clues in a mystery.” In his research, Alramly came across Jean-Claude Michel’s book on the Black Surrealists, a group of students and writers who “identified with some distinctive traits surrealism happened to share with traditional African art and literature: a common belief in the power of words, of objects, and of external occurrence.” New Black Surrealism is also a reference to this forgotten movement. “You don’t hear of Black Surrealism as a movement of itself in art, and that’s one of the things I want to do when I talk about defining movements or subcultures … giving space to those things usually left out of history,” Alramly explains.

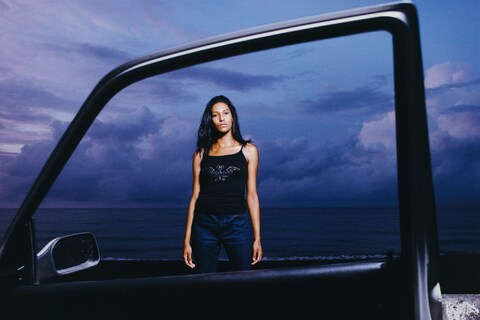

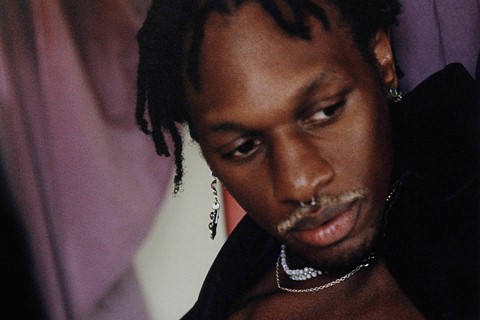

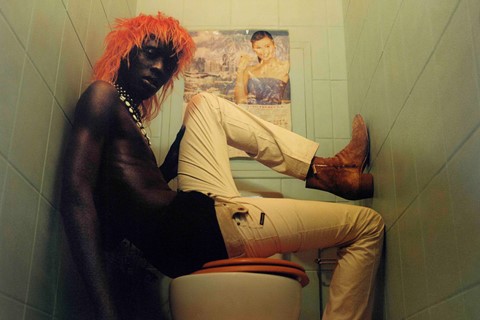

Naima explores the notion of a “New Black Surrealism” through a group of formidable artists spanning the diaspora, including multidisciplinary artist Rhea Dillon, sculptor and photographer Dozie Kanu, and painter Naudline Pierre. “If you look at the work of Marcus Jahmal, Pol Taburet, Frank Dorrey, or any of the artists that are featured in this movement, what do you see? This amalgamation of images – figures of Caribbean mythology, cops, Black bullfighters, liquor stores, Memphis rap album covers … a free association of images that make up the contemporary Black subconscious,” says Alramly.

Although the sensibilities of the artists differ, certain motifs emerge: layers of context and meaning, invisibility vs. visibility, and an overall desire to focus on the subconscious rather than the body. At heart is a refusal to be bound to one singular thing; each of the artists featured push back against the pressure to make art that is “representative”, or only rooted in figuration.

For Naima’s design, Alramly wanted to “maintain the playfulness of a fanzine.” This is expressed through the publication’s graphics and interface – users can interact with references by hovering over them – and the “Stories of Cultural Interest.” The first issue’s “Stories of Cultural Interest” features artists who are all “crests of a convergence of contraries”: One notable contribution in the series is an essay by punk-rock legend singer and writer Richard Hell.

Alramly hopes Naima can offer “a peek into the minds of artists” and a way of reading “other than the classic form of an essay.” “The entire theme is one large essay, one large idea that a reader can access through multiple minds,” he says. “Naturally, as we look for and encourage subcultures and movements, we want to reach those readers that are curious about art and literature and where they can find a space that resonates with them.” Alramly has ambitious plans for the publication, including an exhibition on New Black Surrealism and a video series focusing on studies, archives, and houses. “It’s my form of documentation,” says Alramly. “It’s about capturing a generation and giving shape to what’s going on.”

Discover Naima here.