Exteriors at Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris (until 25 May 2024) expresses the ineffable experience of modern, urban life

In French, a flâneur, meaning ‘one who wanders aimlessly’ has its roots in the 19th century, used to describe the leisurely, modern man as a passionate spectator of cosmopolitan life. Over 150 years later, feminist writers such as Lauren Elkin reclaimed the word with ‘flâneuse’ – transforming the exclusively male term into an expression of female subjectivity, gaze and way of being in the world.

Paris, in particular, has always inspired a rich history of female spectatorship – a theme at the heart of Annie Ernaux’s Exteriors (1996). The striking yet sparsely composed text was written between 1985 and 1992, when the Nobel Prize-winning author was living in the Parisian suburb Cergy-Pontoise (where she remains today). As the ultimate flâneuse, Ernaux explains: “I sought to describe reality as through the eyes of a photographer and to preserve the mystery and opacity of the lives I encountered.”

Ernaux’s book is the inspiration behind the latest exhibition at Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP), Exteriors: Annie Ernaux & Photography, curated by Lou Stoppard, featuring 150 works by international photographers. “When I first read Exteriors I found Ernaux’s capturing of an outward gaze fascinating,” says Stoppard. “Her writing has a visual, photographic quality.” In homage to the visual writing of Ernaux, Stoppard’s show pairs text and image, bringing to life the author’s distinctive gaze: “My gaze resembled the glass surfaces of office towers, reflecting no one, just the high-rise buildings and the clouds,” she writes in the introduction of her book.

Although a beloved figure in France since the early 1980s, known for auto-fictional books such as The Years, Getting Lost and Happening, it was only upon winning the Nobel Prize in 2022 when Ernaux received international recognition. “When I first came across Ernaux she was definitely having a moment and receiving increased attention amongst a younger readership, especially from women,” says Stoppard. “Shortly after I pitched the idea of Exteriors to the MEP, she won the Nobel Prize. It was an amazing moment, and she absolutely deserved the celebration – but I also felt an increased responsibility to get the show right.”

In 2022, Simon Baker the director of MEP, invited Stoppard to spend one month living in Paris as curator-in-residence, during which time she researched the museum’s vast photography collection, drawing from international photographers: Daido Moriyama, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, Issei Suda and Garry Winogrand amongst countless others. Stoppard selected photographers whose deeper interest in all aspects of modern life aligned with the prose of Ernaux. “Garry Winogrand said that ‘all things are photographable’,” remarks Stoppard. “And to me, that really captures Annie’s writing.”

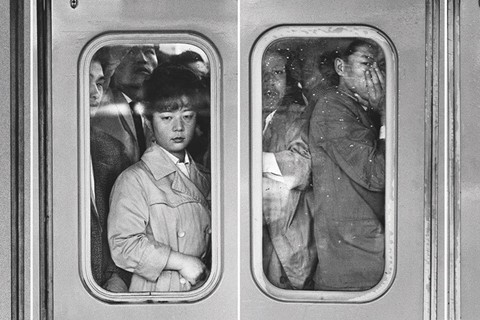

Travel is a prominent theme running across both Exteriors and the MEP show. In particular, the daily tedium of the commute: traversing between suburb to inner city, exterior to interior and back again. Photographs such as Johan van der Keuken’s Rue de Rivoli 1957, to Janine Niepce’s, to Social housing in Vitry, a mother and child, 1965, offer striking contrast between the centre of Paris – its boulevards, glitzy shops and Haussmann buildings – to the grey concrete outskirts of the sprawling city, where immigrant and working-class communities have historically been pushed to. “Exteriors is about conveying distance,” says Stoppard. “Distance in the sense of a fractured identity, but also in terms of feeling distanced from a centre.”

Born to working-class parents, much of Ernaux’s writing contemplates French class structures and offers a socio-political gaze. “Her writing is a form of class transcendence,” Stoppard explains. “In Exteriors, she’s giving dignity to the inhabitants of Cergy-Pontoise.” From growing up close to Milton Keynes, a British 1960s new town, Stoppard resonated with Ernaux’s descriptions of Cergy-Pontoise, which she describes in Exteriors as: “a place suddenly sprung up from nowhere, a place bereft of memories … some no man’s land halfway between the earth and the sky.”

The works included in the MEP exhibition give integrity and gravitas to the individuals living in such communities, but also the types of labour often denigrated in high art. Janine Niepce’s photograph, Restaurant époque 1900. Le garçon de café, 1957, reveals an overworked waiter carefully balancing trays, while Clarisse Hahn’s photograph Ombre (Shadow) 2021, shows greengrocers and shoppers loading plastic bags with vegetables in the snow. “Ernaux believes everything has the right to be chronicled, noticed, recorded or discussed,” says Stoppard. “There’s no such thing as a lesser truth.”

Stoppard found herself returning to one particular verse from Exteriors, in which Ernaux writes: “I believe that desire, frustration and social and cultural inequality are reflected in the way we examine the contents of our shopping trolley or in the words we use to order a cut of beef or to pay tribute to a painting … that the violence and shame inherent in society can be found in the contempt a customer shows for a cashier or in the vagrant begging for money who is shunned by his peers – in anything that appears to be unimportant and meaningless simply because it is familiar or ordinary.”

“Annie is very attuned to the world, and the inherent shame and even violence of modern, public spaces – the kind deriving from how people treat one another, or are subjugated more broadly by society,” explains Stoppard. A scene in Exteriors involves the author passing through the corridors of the Metro, averting her gaze in shame as a blind man at Saint-Lazare station begs for money. He is ignored by everyone including the author herself (“I walked by at a respectable distance, like those who give him nothing”). That sense of disregard is felt in the photograph by Martine Franck, Paris, 1979, in which an old, dishevelled man sits alone on the floor of the street.

Exteriors – neither the book or exhibition – intends to be overly didactic or moralistic. But both quietly speak to the social divisions running along class and even gendered lines. Stoppard notes it probably wasn’t a coincidence that Ernaux wrote Exteriors when her children had left home – giving her the space to observe the world with fresh eyes – suddenly liberated and unencumbered by maternal or domestic duties. “Since having my daughter I’ve noticed that my own presence in public spaces has changed,” remarks Stoppard (who had her first child less than a year before the exhibition opened). “It changes the way you move through a city or public space. I don’t look at anyone else because I don’t have time.”

Ernaux’s Exteriors can be interpreted as a claiming of public space – as a woman, writer, mother and flâneuse – who wishes to observe unapologetically but also compassionately. Dolores Marat’s striking photograph The Woman With Gloves evokes this kind of feminine agency – the mysterious image of the woman in profile clutching her gloves as she descends an escalator resembles Ernaux herself. “So many people thought the woman in that photograph was Annie.” Stoppard says jokingly. “I can understand why. But Annie finds those observations funny – she insists she’s never worn her hair like that.”

When reading Exteriors, the physicality of Ernaux’s presence is always tangible – reading her work is like standing in the shadow of a photographer. Stoppard’s Exteriors reflects this idea, bringing together works that convey a sense of proximity through a journey, as if we are commuting alongside the author – astutely perceiving the world from her perspective. “Exteriors is really about presence,” says Stoppard. “And how the act of observance leads to one’s sense of self, but also a deeper connection to the world.”

But the exhibition also investigates the unique relationship between writing and photography. Stoppard’s show seeks to answer the questions: can one write photographically? Or can one photograph reality in a literary, poetic way?

Like the daily journey of a commuter, the exhibition ends at the place of origin. “The very last works in the show are by Johan van Der Keuken, with the final photograph simply showing train lines and tracks,” says Stoppard. “The idea was that as you leave the exhibition, you return to the exterior like Ernaux – to Cergy-Pontoise.”

Exteriors: Annie Ernaux & Photography is on show at Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris until 25 May 2024.