As a retrospective of Rankin’s work for Dazed opens in London, the photographer and magazine’s co-founder tells the stories behind five of his most memorable images

Rankin’s photographs – particularly his portraits of celebrities – defined the 90s and early 2000s. In his images, celebrities appear stripped back and laid bare in a punk protest against the uber-glossy aesthetic of the decade before. Dazed, the magazine Rankin co-founded alongside Jefferson Hack, came to embody that ethos, challenging the notions of what fashion and portraiture could be through photography.

For Rankin, capturing the essence of his subjects began with rethinking the industry itself: “I didn’t want to be derivative of another photographer, so my approach to portraiture became about how I wanted to work with the subject. From a very early stage, I decided that instead of it being a transaction, where they stand in front of me and I take a picture of them, I would make something with them.”

In Back In the Dazed: Rankin 1991-2001, a new retrospective at 180 Studios in London, the photographer’s iconoclastic snaps taken for Dazed show how he used pictures as a form of protest. Documenting the LGBTQ+ community, setting flame to synthetics, and capturing creatives with cult followings, Rankin’s work deftly mixes androgyny, angst, and art.

Here, to coincide with the exhibition’s opening, Rankin tells the stories behind five of his most eye-catching images.

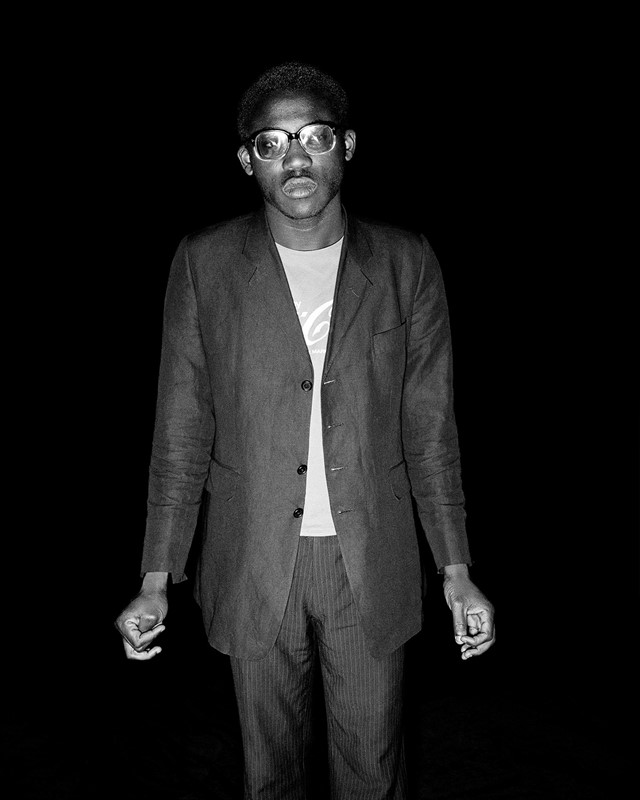

Edward Enninful, Death Masks, 1994

“It was very early on in my relationship with Katie Grand, and we were always wondering what we could do to challenge the mainstream. I was obsessed with death, and I think I said, ‘I wonder what somebody would wear in their coffin to their funeral?’ She built on it, and said I should ask stylists and fashion editors. Each of them came along with their own outfit – I think [Enninful] had on an Agnes B suit because it was his most comfortable outfit. I think he asked me, ‘What should I do?’ I said, ‘No, no, just stand there!’ That was the first time I met him.”

Björk, Nanu Nanu Björk Calling, 1995

“It was me on my own with [Björk], because I couldn’t afford an assistant. We were out on the street while she was doing a gig in upstate New York. I had myself, a reflector, a small flash, my camera, and some film. That was it. It was very windy – suddenly, the wind hit her and swept her hair across her face. I think most famous people who are used to being photographed would immediately put their hand up and move it away, but because it was her, she didn’t do that. She just let it go. I’ve got so much respect for her because she gave me a lot of confidence about being myself.”

Highly Flammable, 1997

“I was at a party with my partner at the time, and synthetic clothes had just gotten really fashionable. They said, ‘The whole fashion industry is here, and if someone set light to ‘em, they’d all go up in flames.’ It was so dark but so funny at the same time, and I thought, ‘How can I set light to people without actually setting light to them?’ I was inspired by this shoot I did with Pulp where there were all these cutouts. So I did a shoot in the Dazed studio, made life-size cutouts, and went into the streets around the office and set light to them.”

PJ Harvey, 1998

“I shot PJ Harvey about four or five times. She was always so incredible to meet and collaborate with because she was very trusting. Looking through the Dazed lens is to look through a much more gritty lens, [it’s] less sophisticated image-making, a little more raw. I went to visit her at her home, which was off a little road in the country, with one assistant. Here, I was trying quite hard to photograph her against a plain background because that always made the better cover. She ended up being so in love that she became another one of those people that really supported Dazed. I can’t underestimate how supportive she was.”

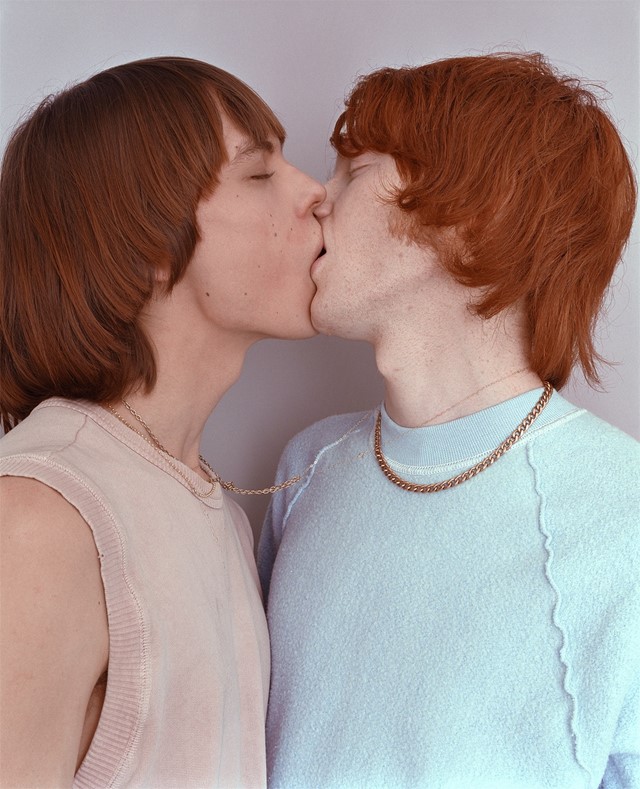

Feel It, Aron & Chris, 2000

“Robert Doisneau’s photograph, The Kiss, inspired me to do an exhibition and book called Snog, which was lots of people kissing really close-up, so close you couldn’t tell who they were or what they were doing. We were inspired to do a fashion version of it for Dazed, casting androgynous models so you wouldn’t know what anyone’s sexuality was. An intrinsic part of the shoot was to make the reader question what their genders were. It was one of my favourite collaborations with Alister [Mackie].”

Back In the Dazed: Rankin 1991-2001 is on show at 180 Studios in London until 23 June 2024.