The roles of ‘mother’ and ‘artist’ haven’t always been viewed as compatible. Motherhood is usually perceived as a woman’s role, coded as domesticated, nurturing, and highly attentive, fussy even. The figure of the artist – particularly set against the backdrop of a historically male-dominated art world – has been placed in contrast to these cliches, as free-thinking, brave, and fiercely independent; the unencumbered “male genius”.

Art critic Hettie Judah’s new book, Acts of Creation, however, meets artists who have dismantled and disproven the notion that these categories and qualities are at odds. As the painter Alice Neel once said: “I used to feel guilty about being an artist, because I used to think the way the normal world thinks: there’s a certain function for women.” Yet, after having four children, one who passed away young, and another who was taken away and raised by the father, Neel harnessed the sense of conflict she felt between motherhood and her art practice by injecting it into her paintings. She put her children in the frame – literally – and painted pregnant women repeatedly, some nude, in ways that showed not only the beauty but the brutality of motherhood.

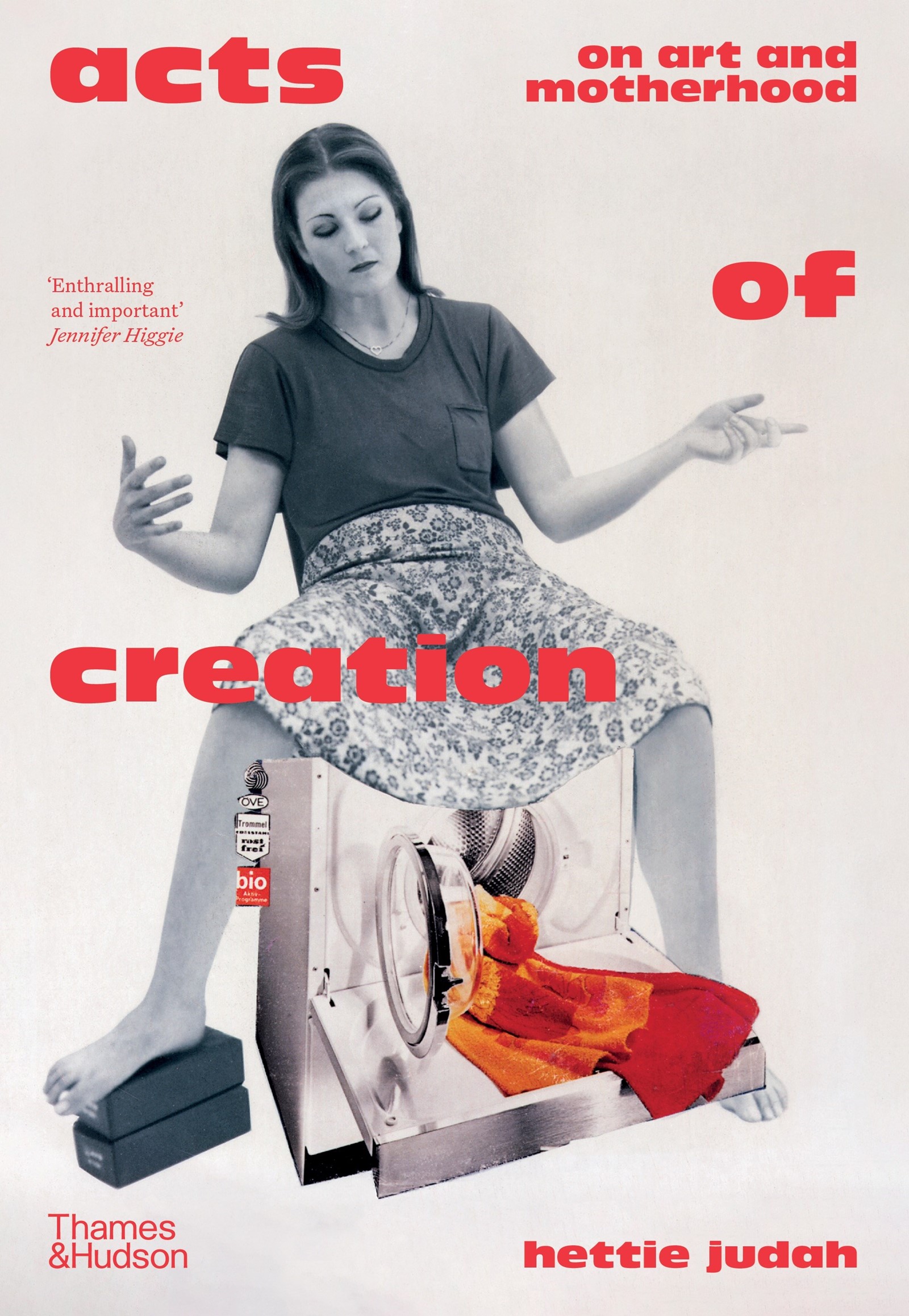

According to Judah, cliches and expectations are tools with which to diminish women and nonbinary parents, as well as to scrutinise them. “There are these enduring conservative assumptions about what a maternal mother would be,” Judah tells AnOther. “Our abiding idea of the rebel tends to be rebelling against the domestic realm. That puts the mother at the polar opposite of the definition of cool.” Yet, look at the work of an artist like Valie Export, whose work features on the cover of Acts of Creation, says Judah. Export had kids when she was making Action Pants: Genital Panic, the photographed performance where she sits on a bench with her legs open, holding a machine gun, trousers torn to reveal her genitals. “She was such a punk. But when we think of mothers in art we still think of the Madonna and Child … self-sacrificing perfection.”

Judah’s book reveals instead, as curator Brian Cass puts it in the foreword, motherhood’s “radical dissenting potential”. Charting art’s intersection with motherhood as a subject from the Medieval and Renaissance periods to today, it also shows how mores around gender and sexuality – and therefore motherhood – have changed with the times, or from place to place, and how artists have reflected these contexts.

At the Hayward Gallery Touring's group exhibition Acts of Creation, curated by Judah, which recently opened at Midlands Art Centre in Birmingham, one of the most striking works on display is Jamaican-American artist Renée Cox’s self-portraits from the Yo Mama series from 1996, which portray a muscular Black mother in the nude carrying her baby, an image that can be seen as in dialogue with and challenging the US stereotype of Black mothers as unfit or “welfare queens”. Another is Paula Rego’s gender charcoal drawings of women squatting in pain in backstreet abortion clinics at a time when they were illegal in Portugal, centring humanity, not victimhood.

If Judah’s goal was to showcase work that busts stereotypes around what makes a mother, as well as what makes a mother who’s an artist, she also expands both categories by including artists who are not mothers, whose work that deals with surrogacy, abortion and miscarriage or choosing not having a child.

Tracey Emin’s video work How It Feels is on display, transporting the viewer to the steps outside the doctor’s office where Emin had an abortion in 1990. In it, the artist shares her guilt and confusion over the decision in a meditation on the complexity and potential incompatibility of becoming a mother alongside being a young working-class artist. The absence of a child becomes the artwork itself.

Similarly, New York artist Miriam Schaer’s works Babies (Not) on Board, features testimonies from women who had chosen not to become mothers embroidered onto children’s clothes, including phrases like “you better hurry up” and “childless women lack essential humanity” – phrases and stereotypes so familiar they seem to reach through time and across continents. The care put into the embroidered clothing reflects the care that might have been directed towards an infant.

Overall, perhaps one of the most prescient and progressive contributions of Acts of Creation then, is to depict motherhood as much more than a biological act, but also a political one. Discussing photographer Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table series, Judah points us to critic bell hooks’s essay Homeplace, which describes the domestic realm not as a place of oppression, as the predominantly white Women’s Movement would have it, but as a site of care practice for Black women, a refuge from a world of violent hostility, and “a crucial site for organising, for forming political solidarity”.

Mothering here becomes more than familial and about ancestry in the broader sense, speaking to a lineage of mothering among marginalised communities that goes beyond DNA, and one that we might trace to through the constructed families of ballroom culture to today’s slang use of “mother” – particularly among queer and trans people – to describe a femme who is iconic and that we can learn from.

It goes to follow that in the last chapter of Acts of Creation, called Mothering: The Family Reborn, Judah fully turns her attention to these kinds of modes of reinventing motherhood, looking at representations of collaborative and queer modes of parenthood since the 70s, and in the process, reminding us they have long been there. Judah points to Cathy Cade, who documented lesbian mothers and alternative family constellations in the 70s in San Francisco, including her own. In one image, Cade poses with her partner, Kate, her son Guthrie, and their flatmate Pat, with the tools of their various trades laid out before them (photographer, artist, mechanic, children’s toys etc). The image was taken against a backdrop of homophobia in the US led by the Christian right, and is an assertion that lesbian families existed at a time when children were being forcibly removed from gay parents.

20 years later, in the 90s, lesbian artist Catherine Opie made Self-Portrait/Cutting, photographing her unattainable desire for a queer family as someone gay and in the S&M community by scratching the image of a house and family into her back. Later, in 2004, when she did have a child, she created a new version of the image, Self-Portrait/Nursing, which depicts Opie holding her son with a scar of the word “pervert” faintly visible on her chest, an iconic image because of its rarity in depicting a butch mother nursing, adds Judah.

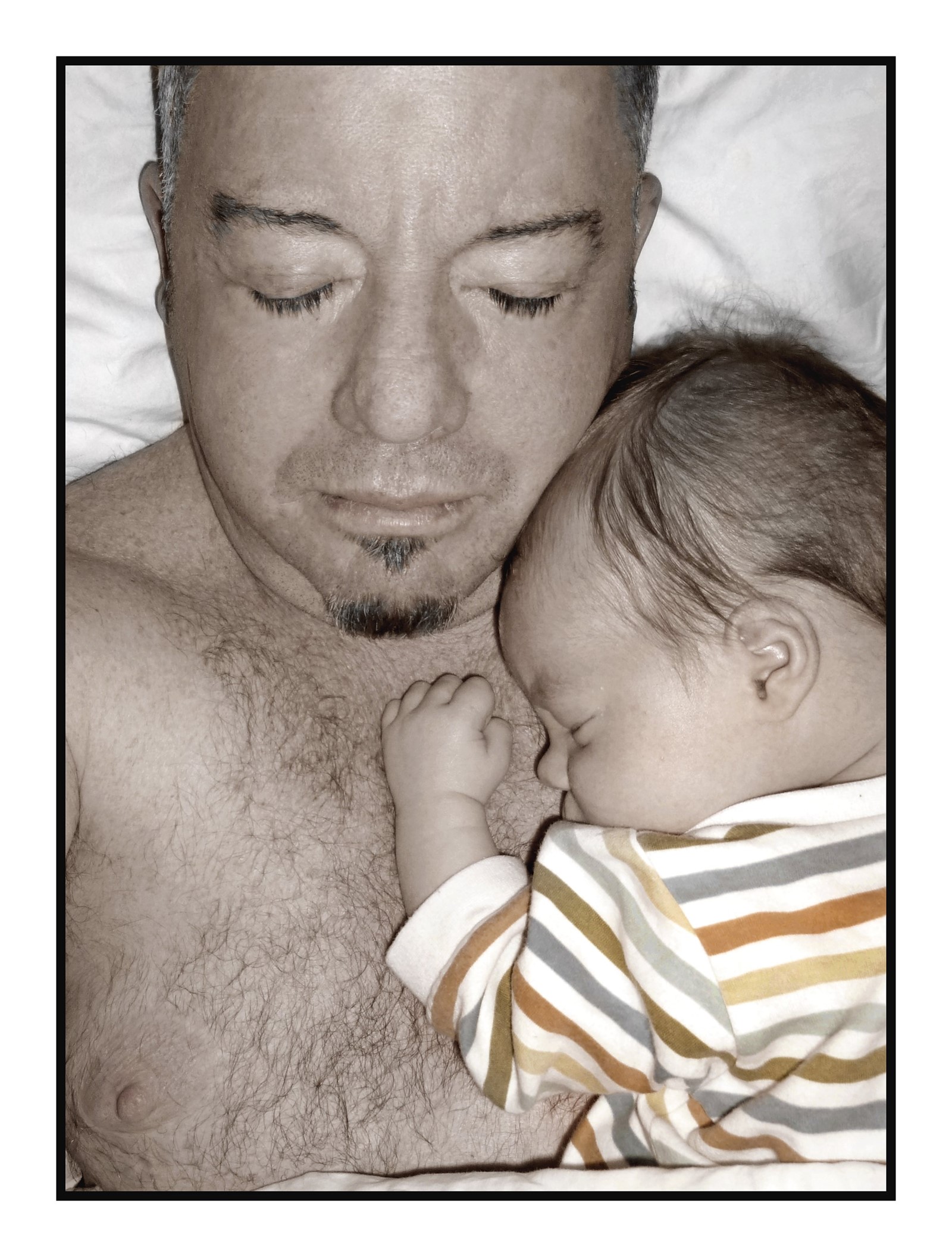

Ask intersex and nonbinary photographer and parent Del LaGrace Volcano whether they can name queer representations of parenthood that affected them, and after a pregnant pause (excuse the pun), Opie’s work is the sole reference Volcano can come up with. Hence, in part, why they decided to contribute to the slim canon of works around alternate family structures. In the image MaPa (2011) – named after the nonbinary parenting name Volcano goes by – the artist holds their baby, Mika, whom they co-parent. “I fell in love instantly in a way I had never known possible. I was never asked when I was going to get married and have kids so I never expected to. But even now, my gender queerness is evident and that sometimes causes problems with governmental agencies, the primarily heterosexual teachers and school system, and in hospitals – I’ve been challenged about if I am the ‘real’ parent of my kids.”

Volcano raises their children to be gender-questioning, and both identify as nonbinary. “This kind of open-gendered parenting, you have to model it. We can’t be what you can’t see, and most of what we see of parenting is heteronormative or homonormative.” Yet there is also an impulse, right now, to resist making their family life visible. “We’re not sure how public we want to be given the political climate,” says Volcano, of the hostility towards queer and especially trans families in the US, UK and beyond. “The whole visibility argument in the LGBTQIA+ movement is we had this idea is all publicity is good publicity. But visibility is not an end unto itself.”

Artist mothers still face barriers (practical and social) in succeeding in the art word, still barely supported and treated as hobbyists. Women are still distrusted to make decisions about their own bodies and abortion is still stigmatised, as the overturning of Roe v Wade demonstrates. Queer and multi-parent families are discriminated against, as global attacks on IVF access and parental rights for same-sex couples are underway. Judah believes art can bend perception, or make material change; Rego’s backstreet abortion drawings, for instance, have been credited in swaying the 1998 referendum on abortion.

“Just celebrating images of motherhood without questioning the context in which they’re shown or the risks taken by those artists isn’t enough,” Judah concludes, “In the political context of now, that’s especially important.”

Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood is published by Thames and Hudson, and is out now.