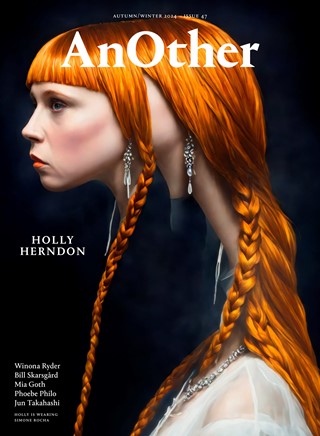

This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine:

They’re multi-hyphenates with many parallel realities. It’s the expansive nature of their practice that makes their work so prescient. It reflects not only what technology can do within their own craft but in the wider field. Together, the artists envisage an ecosystem for all in their field, closely examining what the use of artificial intelligence may mean in the world.

Holly Herndon (named among the 100 Most Influential Voices in AI in Time magazine last year) and Mat Dryhurst have the generosity to open-source their work, publishing much of their studio research. On their podcast, Interdependence, they consistently host urgent conversation. And then, of course, there is their organisation Spawning. This country has a great history of artist-run spaces that may be traced back to Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas in the 90s. Today, in the digital sphere, Spawning is an artist-run space that is constantly building on how we interact with AI, while considering any use of data from an ethical standpoint.

I am excited to celebrate the Berlin-based artists and technologists ahead of The Call, their forthcoming show at the Serpentine Galleries. Since the exhibition’s inception, Herndon and Dryhurst, who are also life partners, have been recording the voices of singers in choirs across the UK, emphasising the weight of ethically sourced data and ownership. On this occasion the choirs are co-owners of the data, from which an infinite soundscape may be created. We welcome everyone to visit The Call at Serpentine North, where we will collectively and critically address the issues of privacy, data, collectivity and – lastly – the divine.

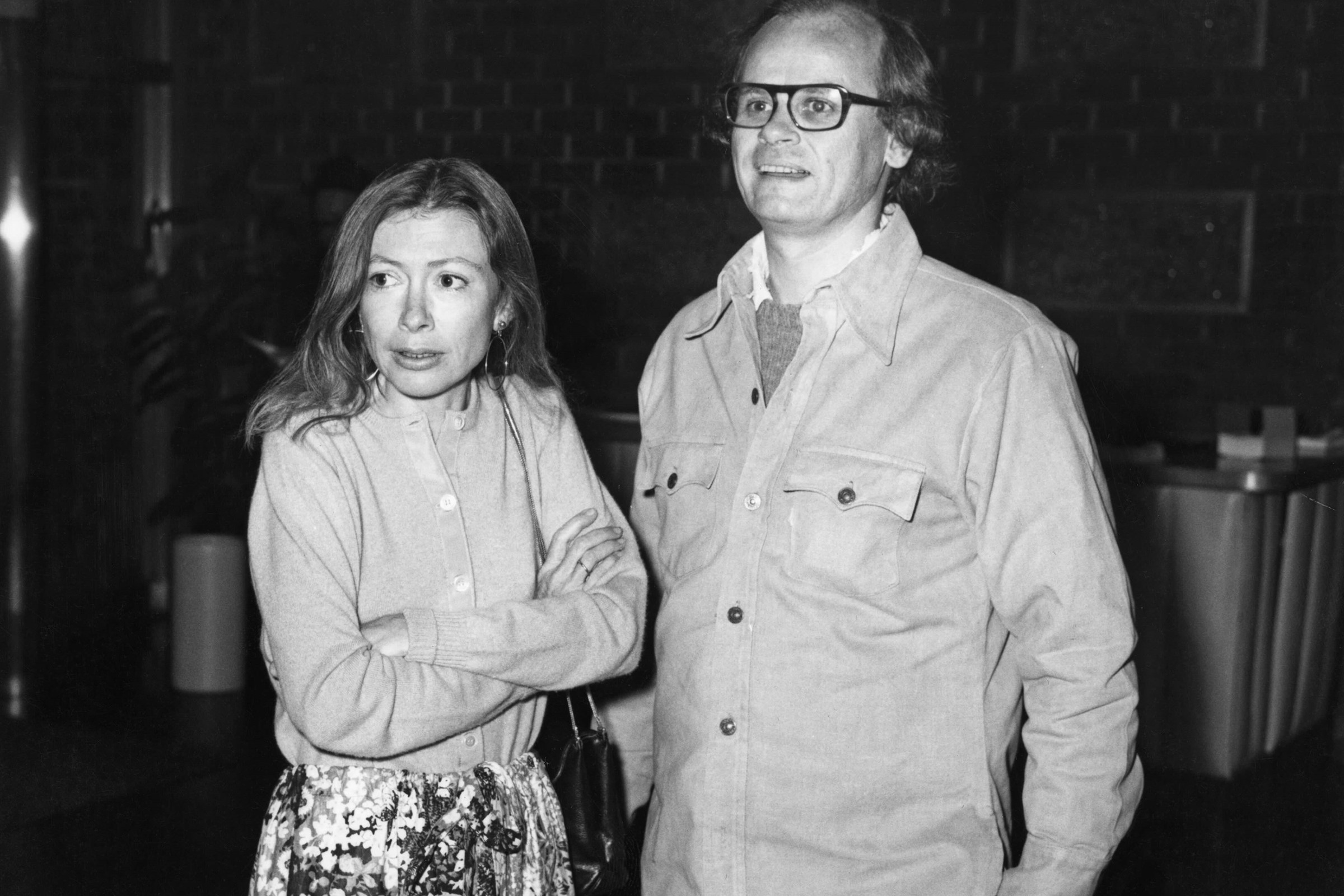

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Eva Jäger, curator, arts technologies, at the Serpentine Galleries.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Can we begin with the beginning? How did you come to AI? We are working on your show for the Serpentine Galleries and we are so excited. You are at the forefront of artists working with AI in the 21st century, but people don’t really know where you started.

Holly Herndon: It’s a good point – AI is not a new thing. We’ve been going through waves for decades. We’ve gone through some AI winters. I like to joke that we’ve been in an AI hot girl summer since 2017. That was a particularly fruitful year for research papers being released – a lot of code and a lot of public-facing AI research was made available. That’s when we started playing around with it.

Mat Dryhurst: Yeah, the Transformers paper came out, and that represented a major breakthrough. The other big breakthrough was the fact you could run quite powerful systems at home, which parallels a lot of the uptake in consumer adoption of cryptocurrency and mining, with people using the new GPUs [graphics processing units] on gaming PCs that were out. It was a perfect storm.

But yes, it’s been around for ever. AI work never caught my interest until 2015, when deep learning frameworks like TensorFlow meant that you could start to run these models at home and tinker with them, and it became obvious that, one, this is going to be a big deal, and two, there are plenty of reasons to want to intervene with where it is going.

HH: And a lot of the research, especially in the music world, was around automated composing. There’s a thing called MIDI [musical instrument digital interface], which is a way that computers speak musically to each other – a lot of people were making automated MIDI scores. That was not so interesting to us because we were dealing with sound as material. We wanted to generate audio material because we love the sensual quality that audio has.

The audio generated between 2016 and 2020 has a particular timbral quality that sounds ghostly, quite low fidelity. I’m almost nostalgic for the sound of it – that was when audio generation research was just starting to take off. That’s where our practice also sings, because we have so much experience manipulating and transforming audio.

“AI is not a new thing. We’ve been going through waves for decades. We’ve gone through some AI winters. I like to joke that we’ve been in an AI hot girl summer since 2017” – Holly Herndon

HUO: How did you connect to the early days of cybernetics and to that history? The late cybernetic pioneer Heinz von Foerster told me that, in a way, the 21st century will be about thinking in circles – A leads to B, B to C, C can return to A – circular arguments more than linear ones.

Now, you began Holly+ as a machine-learning model trained on Holly’s voice that would allow users to create artwork, and you have since added more dimensions to that. There’s a free version of Holly+ available online. And through that you anticipated the future of music, the future of your own medium of infinite media.

At the same time, you don’t only explore this for your own practice, which a lot of artists do, but you also look at the whole ecosystem – the artistic, technical and socioeconomic aspects of these technologies – and reflect upon the economy and what it means for other artists. You have a podcast. It seems there are two strings to your practice.

HH: It’s all intertwined. I released my first studio album, Movement, in 2012, when I was coming to terms with the computer as my primary instrument and came to the realisation that the computer was the most intimate instrument that anyone has ever known. At the time, people weren’t really accepting it as an instrument and I was like, “Wow, this machine knows everything about me, it’s mediating all of these relationships. How profound is that?” And then when Mat and I made Platform [released in 2015], we started to think about the broader network that the computer interfaces with so that it touches on distribution and collaboration. Also, at the time, we were thinking a lot about surveillance and how our every movement may be training a potentially unseen algorithm or even a government agent.

So that was when we started to expand beyond thinking about the media that we create into systems. We were training our own models on consensual data – a lot of people playing around with AI these days are working with models that have already been trained on vast amounts of data that’s been scraped from the internet. We were making our own training data. That informed our politics early on and informed our approach to machine learning – it really required a system-wide level of thinking because it can feel like a monolithic issue to deal with.

MD: So, in software, you have this principle called dogfooding. If you’re a software developer who has a particular idea about how the world should work or how someone should keep notes in their diary, say, dogfooding is the process of using it yourself first. If the software developer themself isn’t using the software, how can they expect anybody else to use it?

Putting Holly’s third album, Proto, together in 2019, we observed early on that training data was going to become a massive culture war, but also a massive problem for people to digest economically. So we put together the training ensemble under our own protocol to demonstrate that we can get really good results from consenting data. With Holly+, we demonstrated through dogfooding that you could open-source your voice and decentralise permissions and it became a canonical example for people wanting to share models of themselves.

That spiralled into the work that we do under Spawning, where we’ve put together the only widely used consent protocol for AI training data. That’s being debated. It informed the AI Act. These are all the same things.

HUO: At the Serpentine, we’ve worked with AI for ten years. It started in 2014 with Cécile B Evans’s AGNES, which was a chatbot on our website. Now we’ve declared that 2024 is the year of AI at the Serpentine. Can you tell me about how you source your data ethically and if you have any advice for other people on how to source data ethically?

HH: There are two different approaches. One is sourcing public domain data, from the Smithsonian for instance. There are many public institutions that provide data you can use ethically. Actually, Source.Plus, which we recently launched with Spawning, just put together an incredible training data set for people who want to create large models without any question of where their data is sourced from. But the approach we take is a little different.

We see training data as a new art form that’s a little underrepresented in the AI field now. We see making training data as creating these little mind children that we can send to the future. While the model architectures will change and be updated over time, the training data is evergreen – you will always be able to make new models if you have original

training data.

MD: Yes, there wasn’t really a solid public domain data set. Source.Plus is the largest available public data set – it’s 200 terabytes of public domain imagery. That is plenty good enough to train a competitive model. On the consenting data question, part of the reason we did this now is that the latest experimental architectures for training an image model don’t require billions of images. We’re transitioning from that phase from using LAION-5B, or the big data sets that contributed to image generators like DALL-E, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion. It’s possible now to train an image model on as few as 12 million images. The importance though is that those images are well curated, which is an interesting transition.

We’ve been arguing this for years, but the industry is finally coming round to the conclusion that the output of your model is pretty much the data that goes into it. Which is an interesting new dimension for artists too. When you understand that your artwork is not only being made for a human audience, but also for training data, this new dimension that all work will find itself filtered through, you can then start to think about producing deliberate training data. This is the origin of our songbook, for example.

“So everyone is in agreement that the future is most likely going to be run through these incredibly powerful technical systems and there’s a massive opening for political scientists, philosophers and artists to reimagine how things are organised and structured” – Mat Dryhurst

HUO: This brings us to the choir as a data source, which you’re going to work with for the Serpentine. You have been recording the voices of singers in choirs across the UK. So here you don’t source data from the public domain. This is an original data set, correct?

HH: It is. So, we wrote a songbook, drawing from a hymn style of songwriting. We wanted something that was somewhat open-ended so that people would feel the freedom to interpret the music. They’re all original songs, but the sacred harp style we’re drawing from originated in the UK and then travelled to New England and then to the American South. Every community that picked up the tunes would interpret the songs in their own way, using different BPMs, different ornaments, different styles.

That’s what we’re encouraging all 15 ensembles who are participating in our recording project to do – to take these hymns, play with them and make them their own. We’ve built some games and some improvisation into the beginning of the songbook to get people in the zone of improvising. We’re really trying to capture the sound of each unique group. This is a novel way to create a training set because usually it is quite utilitarian. When I trained my voice for Holly+, I sang a series of nonsense phrases that captured all of the phonemes of the English language, covering the breadth of my vocal range. We wrote the training songs to gather the same information, turning training into music that captures the vibe and the timbral quality of each choir. We’re hopping in a car and driving all around the UK to all these communities to sing together and record them.

HUO: There are different phases for the Serpentine. Right now you are making recordings all over the UK, but then you will bring all that content into the Serpentine North gallery. This gesamtkunstwerk will be designed with the architecture firm Sub, founded by Niklas Bildstein Zaar and Andrea Faraguna. Holly and Mat, together with Bildstein Zaar, you will exhibit your research, technology and soundwork as a durational and spatial experience, welcoming interaction between the audience, the artists and the technology used.

And the North gallery was conceived by Zaha Hadid. Hadid said, “There is no end to experimentation.” So it could not be a better space for you because there is no end to the experimentation of Holly and Mat. Of course the Zaha Hadid architecture has something of a chapel to it – a mini cathedral almost – and you’re working with Sub on the very special display. It’s sacred and spiritual. Can you talk about this spiritual element? It’s a space where visitors will experience the foundations of the exhibition and be able to participate.

MD: We spent a lot of time looking at not just the church as a place of contemplation, but also as an archive. For example, some of the earliest inspiration for this was the great chained libraries. There are quite a few around the UK where the church took on – as have many sites of worship – this idea of being a place where you connect with the infinite, with the transcendent, through an archive. Church architecture was designed to trigger this feeling that you are part of something greater than yourself, whether that’s the acoustic reverberations in the space or the sheer sense of going somewhere where you sing and worship together with people. But it was also seen as a site of passing on history.

It’s a place where you would go to read books. I mean, in many cases one book, but in other cases quite a few. The idea of making the space at the Serpentine both a training space and a place to contemplate where you stand in this great transition, but also to temporarily explore the idea of what public spaces will be, now that we are contributing to these archives greater than any one individual – that seemed like the real opportunity here.

HH: Also, Mat and I have been working with choral music for many years and for us – especially for me, I grew up in a church, singing in the choir – there’s this intertwining of choral traditions and church architecture. We like to think about choral singing as an early co-ordination technology, as a precursor to machine learning technology. We like to see machine learning as something that is from us, in that it is a grand human accomplishment, rather than an alien, other technology. Choral singing is a metaphor for that – it’s greater than the sum of its parts. The church as a part of that has, of course, always affected the sound through the acoustics. It’s also been a place of public expression of emotion. With this new technology, we need to find new rituals and new ways of communion with one another with it and around it.

“I love this image of the dark corridors, of an intelligence that’s outside us. We have these very rudimentary tools to navigate these dark corridors. Those tools are language. They are group singing. They are art ... ” – Holly Herndon

HUO: Now, in a way, communion is important. When Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, he said, “First, it will be for everyone.” Of course, now we have a fast internet for people with money and the internet for those without. It was also the idea that you create a togetherness. It was a utopic moment. As we would realise over the years – as with lots of aspects of social media – it has created, as Eli Pariser writes, a “filter bubble”. So rather than togetherness and communion, it has created division.

But artists have always contributed to this idea of togetherness – exhibitions are basically communions in that sense. Particularly at the Serpentine, where it’s free admission, it is for everyone. How are you going to create this community and, secondly, how do you see the potential for AI escaping the filter bubble?

MD: That’s a big one. I have a lot to say about this. You’re right, the interesting thing about the AI question, specifically the data question, is the real danger of this old utopian dream of the web dying. We are dealing with a completely different paradigm of intellectual property [IP] and interaction. As yet, there’s been a very sluggish response from state governments. We’re in this odd scenario where it’s every person for themselves, stepping over each other to gain advantage, and a real concern we have is that the web will become less free without common-sensical data protocols and ambitious ideas for what the new economy could be.

We like to look at, for example, the enforced collectivity of data sets. This idea that we’re all thrown into a data set together of, let’s say, a billion images or hundreds of voices, as an opportunity to rethink not only how IP works, but how an economy works going forward. It is important to think big because the good news and the bad news is, whether you speak to people in state government or at the very top of the AI industry, they also don’t know where this is going. The tech is leading the conversation. So everyone is in agreement that the future is most likely going to be run through these incredibly powerful technical systems and there’s a massive opening for political scientists, philosophers and artists to reimagine how things are organised and structured.

HH: It would be important to mention here that the word ‘utopian’ is fraught. Part of our practice is to propose alternatives to those being offered by industry, perhaps utopian in spirit, but often pragmatic and directly applicable. One of the key aspects of this project is the data trust. This is an exciting part of the project where we’re piloting a new model for how a decentralised community could govern co-owned data. They will have a data trustee representing their interests and they’ll be able to negotiate the usage of their data moving forward. This is a novel approach to governance of data that could potentially lead to further adoption with more sensitive data beyond choral-singing data. So again, as Mat was saying about the concept of dogfooding, we’re putting provocations out into the world that we think could make the economy around AI work better for everyone, where we don’t think we have all the answers, but we’re trying to pilot new ideas just to test things out.

HUO: Can you explain the data trust a little more? At the Bloomberg conference in Venice we were also all discussing how decentralised communities can own data. What is your advice, on a very practical level, about how readers can own data today?

MD: First off, none of this would happen without Future Art Ecosystems. Without fawning too much, the infrastructure available within Serpentine to explore this stuff is unprecedented. We’re grateful for the opportunity because this is a crazy collaborative effort. The data trust idea invites groups of people who take the leap of faith – trust is a wonderful word for multiple reasons – to say, “I’m producing something of value.” In this case with the choirs, it is their voices. All that work, all of those recordings are going to go into a shared data set comprising different choirs throughout the United Kingdom, and that data set will be owned and governed by all of those members.

So one of the innovations here with the data trust is a data trustee – you could see them like an elected politician – will assume the duty of making decisions on behalf of the group. We anticipate that this mechanism will become more standard. The good thing about doing it with choirs and the very experimental group of people who are taking this journey with us is that there are a lot of kinks that need to be worked out and we’re going to learn those along the way. But as Holly put it, this framework is something that we anticipate, if it’s robust, scaling to sensitive areas.

In the UK, for example, there’s a huge debate about the NHS. What happens to all that health data? One can imagine a scenario in which everybody is glad to contribute to a hopefully anonymised set of health data. That data is then made available, for example, to pilot and produce novel medical research for the benefit of everybody. People then have a say in the work or the data that they produce. Currently there aren’t too many ways that you can do this, but in our minds, it seems like the closest opportunity we have to pilot something that will end up becoming very important.

HH: For the average person who’s just curious about learning more about this, they might want to visit Spawning’s Have I Been Trained?, where they can see whether their images appear in any of the data scraping that’s happened for some of the large public models. Then if you don’t want to be part of that training set, you can opt out. If you have an opt-out option, then we think you can eventually have an opt-in option, where you opt in on your own terms. That will require an entire infrastructure, which is why we’re excited about the data trust project – because that infrastructure must be tested so that every day people can manage their data in a way that’s not burdensome and is also fair.

“The real tension is that people are learning that, with the permission systems and the terms and conditions of the web as we knew it, you’ve contributed a great deal to the internet and you own and have the right to very little of it ... ” – Mat Dryhurst

Eva Jäger: Innovating with trust law infrastructure has a long history. Before 1918 in the UK, you needed to own land in order to have the right to vote. As a workaround, groups gained the right to fractional amounts of land – which still gave them individual voting rights – as beneficiaries of a trust that held one plot. In that case and in this data trust experiment, we’re using collectivised rights to gain bargaining power. Right now there is very little law, if any, specifically around AI models and training data and that’s a huge opportunity to consider what standards we want to set for the ‘right way’ of doing things, like collecting training data.

MD: Yeah, nailed it. What’s easy for people to digest is image models. There’s been a lot of debate, and predictable controversy over the idea that you can go and use image generators like Midjourney, which has been trained on the artwork of living and dead people with no attribution and no method of compensation for the people who contributed that data. With a data trust protocol, we’re close to having a scenario where people are happy to, for example, contribute photography that they have made, and as a result, perhaps own a dividend or a share in any profits generated from a model trained with that photography.

The real tension is that people are learning that, with the permission systems and the terms and conditions of the web as we knew it, you’ve contributed a great deal to the internet and you own and have the right to very little of it in this AI context, but there is nothing to say that we can’t change that. When you’re talking about bargaining power with state governments or large companies, it’s really a better-together scenario. One person alone has zero bargaining power in that context. One hundred thousand people withholding their data and training a competitive model with that data under a fairer mechanism have a lot of bargaining power. I imagine there are going to be many papers written about this because it’s a scalable proposal in an area where we desperately need proposals right now.

HH: We’ve talked about a lot of complex, in-the-weeds issues around machine learning and data but I want to be clear that one thing that is key to all our work – whether it’s a concert or an exhibition – is that there’s a visceral visitor experience that is immersive and emotional. We’re trying to show the beautiful human experience that goes into training models. While this has been a very technical conversation, the experience in the space itself will be moving.

HUO: It’s got to be a multisensory environment. I mean, as Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster said, “Exhibitions need to be extraordinary experiences.” That’s our job. So could you talk a little about xhairymutantx, the project you exhibited for the Whitney Biennial earlier this year?

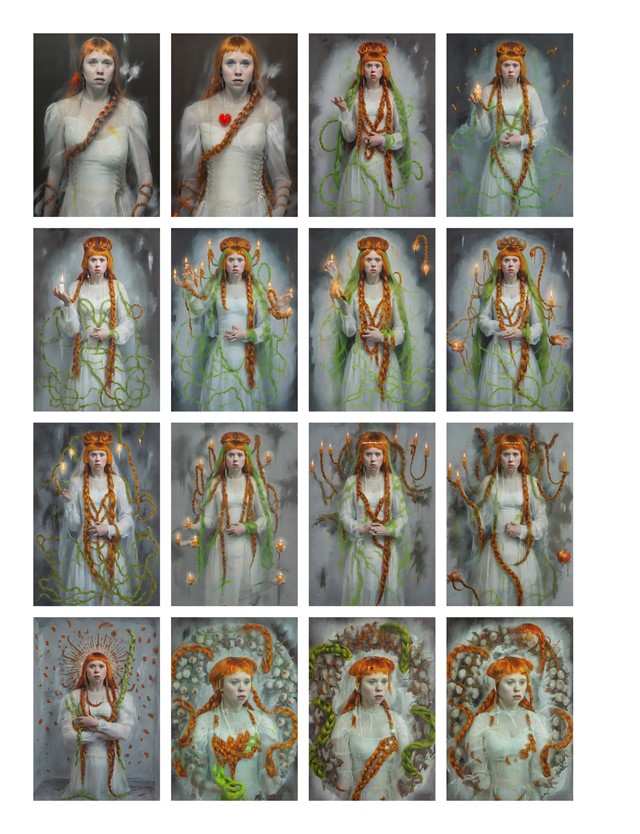

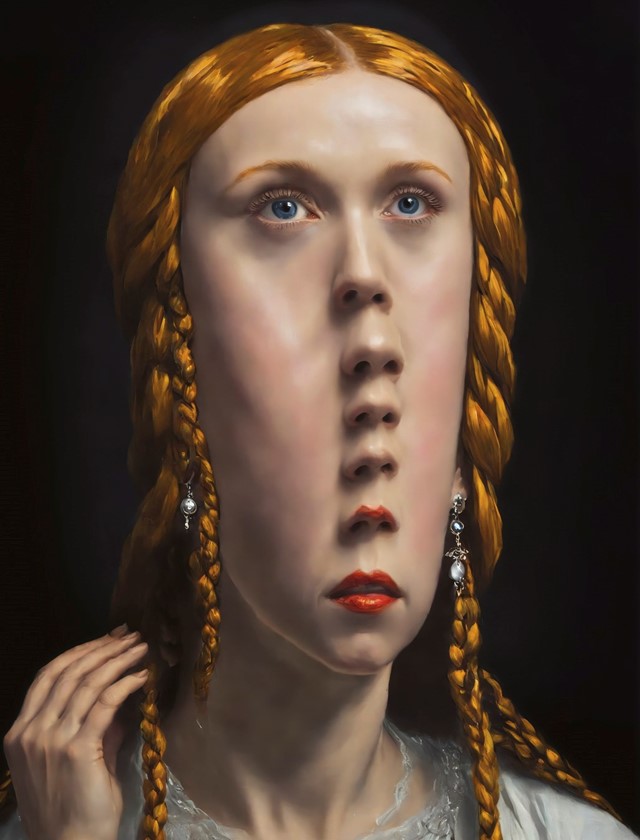

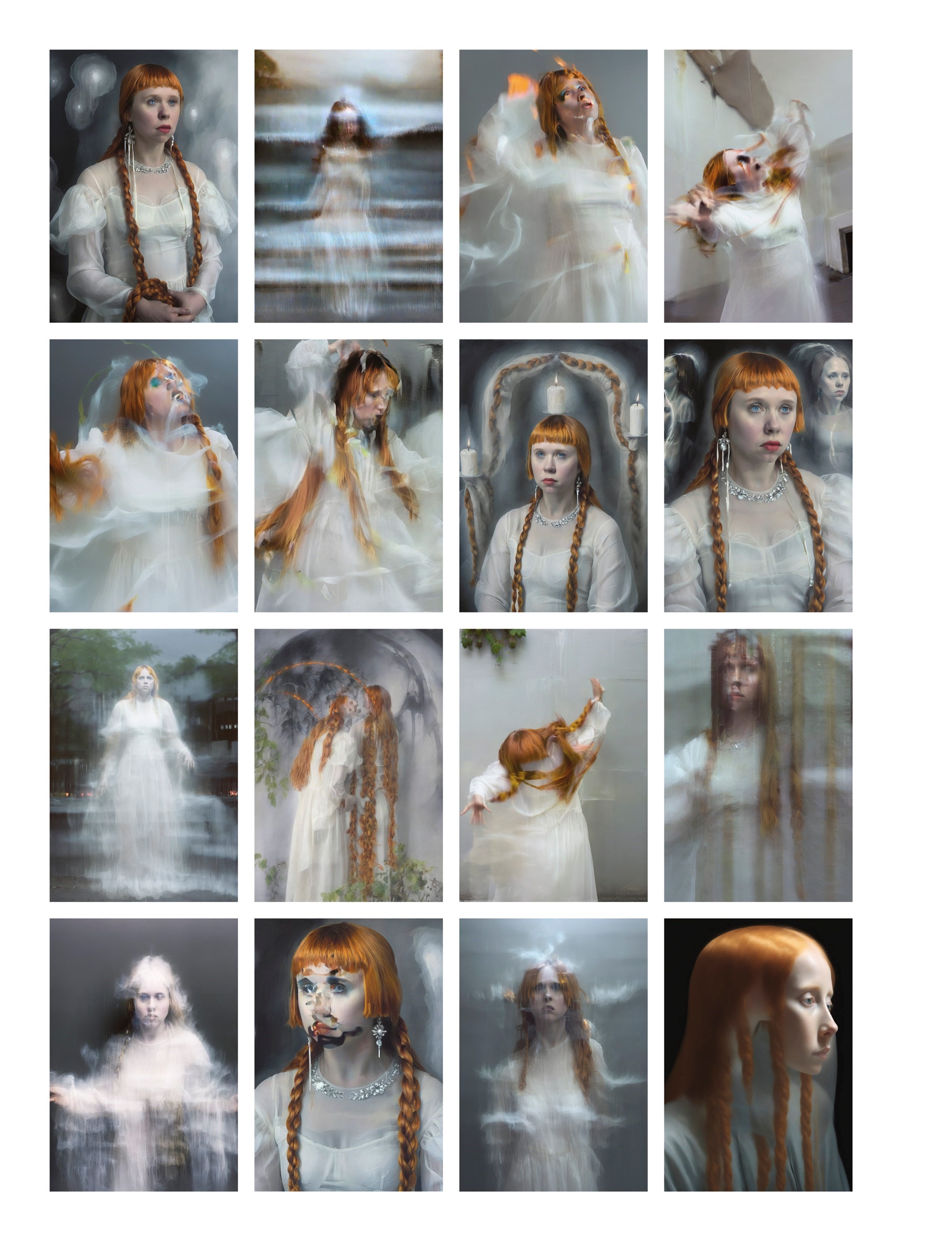

HH: I remember when we had lunch at the very beginning of this process, I was talking to you and Bettina [Korek, the CEO of Serpentine Galleries] about how working with these systems is, in a way, devastating because in some ways it feels like the death of the image and xhairymutantx very much spoke to that. It’s not about the single image. It’s not about the still image, the single photograph, the single moment. It’s about the interaction that you have with a model. That’s something that’s really difficult to show in an exhibition space.

Basically I appear as a concept in machine learning models. I have a CLIP [contrastive language-image pre-training] embedding, which means that my name is tagged to images of me that are scraped from the internet. It turns out that, through my CLIP embedding, you get a pastiche of me, which is an orange haircut. The more famous you are, the higher fidelity your face and your features are. So we asked ourselves, “If the internet is supposed to be this place where you can be whatever you want, this place of promise, but we don’t really have any say in how we appear, is there anything we can do to intervene here?”

We tried some experiments where we completely changed the way I look. And when a model is looking at a lot of data that’s similar and finds an outlier, it’ll just ignore it. We realised that we had to lean into my pastiche. With my pastiche being an orange haircut, what we decided to do was turn me into an even bigger giant orange haircut. So we made a costume where I have this giant orange hair and then we made a training set out of that, and then we made a custom model that anyone can prompt on the Whitney website. Any prompt input to the model will output a Holly-like version with my giant orange haircut. For example, an octopus on top of a mountain has orange braids for tentacles and my signature bangs on top.

The images generated by the public are hosted on the Whitney site, which is an important part of this performance, because when models are trained by scraping the internet, there is a hierarchy of truthfulness, of how concepts are established. The images on the Whitney’s website, which is considered a source of truth over, say for example, someone’s personal blog, will have more weight in the model. So by hosting the xhairymutantx model on the Whitney site and allowing the public to prompt and create thousands of images of me with a giant orange haircut, the next time a model is trained trying to capture who I am, it should mutate me into something that’s even more of a pastiche than what is already in the model. Two life-sized portraits that we generated were displayed as part of the exhibition, but really it is a long-form performance piece between us, the public and machine-learning engineers training future models. As these models search for objective truth, as artists we are searching for subjectivity and plasticity of identity.

“Mat has a great quote that I’m going to use here. He says, ‘Don’t confuse the media for the art.’ That’s key here – we often confuse a WAV file or a JPEG for the entirety of the art, and really it’s the entire network. It’s the discourse around it. It’s the culture that it’s created in” – Holly Herndon

HUO: Please tell us about how much control we have over our own identities – that’s a central question somehow.

MD: Going back to the utopian internet – and we’ve seen the product of these ideas reflected in identitarian subcultures post-internet – one of the first ideas was you can be whoever you want online. I remember, in some of our earlier conversations, the question was, does a person have the right to change who they are inside an AI model? This is a question of real sensitivity for AI companies, particularly because they have this mandate to produce truth.

Hans Ulrich and Holly, both of you have a CLIP embedding. You’ve passed the threshold of fame that you can have a cliché of you spawned in these image models. Do you have any say in how you appear on this new internet? That’s a massive question. Spawning had a project we presented at a Serpentine event last year called Kudurru, where we were experimenting with data poisoning.

Poisoning basically means attempting to manipulate what happens inside a model. That experiment was very successful as a performance – we shut down all AI image training for two 30-minute intervals as a result. But one of the things we learnt from that is that poisoning or changing, manipulating a concept inside a model, is very difficult. So for the xhairymutantx project, we came up with a new technique. We call it cliché poisoning, where the easiest back door to be able to alter something is to find, for example, the distinctive feature that the AI understands about a concept. In the case of Holly, it would be her hair. In the case of you, Hans Ulrich, it might be your glasses, right?

HUO: Definitely the glasses, yes.

MD: So the fastest way you can assert any agency over your concept is to start with the glasses and then make them more extreme and slowly abstract away. I believe, in five years’ time, the project won’t sound as crazy as it sounds now, but it really comes down to that question – do we have a right to be somebody else on this new internet? Nobody is really asking that question because all the conversation is about mistruths and misinformation. Ideally, concepts should be plastic.

Debating what concepts are and how concepts change in this new AI internet seems very important for culture and yet there’s been very little work there. So, xhairymutantx probably counts as the first – although I would argue that it’s probably the first in parallel with Chinese state efforts to change the representation of China in ChatGPT. There are papers about state governments trying to change and basically insert propaganda into AI models.

HUO: Now, one thing you said in a very early meeting was that the exhibition explores the dark corridors of what it means to be an artist in the AI age. What are these dark corridors?

EJ: My long-time collaborator, the philosopher Mercedes Bunz, and I bonded over the idea that the core work of culture – the making of meaning – can now also be made, as in processed, analysed, calculated, by AI. In 2018 this blew my mind, and it still does today – I’m still curious about how AI will change culture as we know it. For me, to be an artist who works with AI is to be awake to this shift and intensely curious about testing cultural production within it. Mat mentioned the embedding space of an AI model, its ‘concept space’. You could argue that this is a new space of creative production. To define what an AI model knows and how it knows it is more significant than any one artefact it produces.

I would say that we’re moving from an artefact-centric way of working to a system-centric one where artists will be more focused on the models they tinker with, the training data they train them on, and the ways that they intervene in larger systems. That’s what’s so exciting about the show we’re working on at the Serpentine with Holly and Mat. It’s all about proposing that the process of training AI models can be an art form.

“I believe, in five years’ time, the project won’t sound as crazy as it sounds now, but it really comes down to that question – do we have a right to be somebody else on this new internet? Nobody is really asking that question because all the conversation is about mistruths and misinformation” – Matt Dryhurst

MD: There’s a great artist and writer, Anil Bawa-Cavia – he’s also a data scientist. He wrote a piece called The Inclosure of Reason. This was back in 2017, I think for Haus der Kulturen der Welt, and there was a metaphor that he came up with, albeit used in a slightly different context. He was talking about the nature of intelligence and this idea of intelligence being something that’s somehow outside us. We walk through a dark corridor and discover intelligence. We happen upon it. We haven’t talked much about the constructionists and Seymour Papert, the theorist, but they had a similar philosophy when dealing with AI at MIT in the middle of last century – that intelligence is something that happens between people, between you and a machine. It’s something that emerges out of interactions and it’s something you discover. We’ve borrowed from that language.

We named our son Link partially after a linkboy – a small boy who used to accompany people in Victorian England, holding a candle through the dark night. This idea of holding a candle and trying to discover something is quite poetic. Nobody really knows where this leads, and that’s even more reason for artists and institutions to take this seriously, because we are learning on the job. Often people will say to me, “Well, where’s this going to go?” I’m like, “Honestly, the good part and the scary part is that the more I learn, the more I’m convinced that an artist who doesn’t know a lot about machine learning has just as good an idea about where this goes as some people working in really large companies right now.” This is uncharted territory and there’s a degree of excitement as well as slight terror.

HH: I love this image of the dark corridors, of an intelligence that’s outside us. We have these very rudimentary tools to navigate these dark corridors. Those tools are language. They are group singing. They are art. These are the tools that help us to navigate the dark corridors and stumble our way through understanding what intelligence is.

I think right now is a fruitful and wonderful time to be a conceptual artist. It’s something machine learning struggles to do well. It’s the context element. Mat has a great quote that I’m going to use here. He says, “Don’t confuse the media for the art.” That’s key here – we often confuse a WAV file or a JPEG for the entirety of the art, and really it’s the entire network. It’s the discourse around it. It’s the culture that it’s created in. All of that is part of the art. So now is a great time to be a conceptual artist. Now is a great time to be a protocol artist, and to echo Eva, now is a really great time to be working with systems and networks.

HUO: I couldn’t agree more. We cannot do this interview without talking about infinity, and in a way notions of infinity seem to change the status of the artwork. I mean, there is an infinity to this project.

Now, obviously the idea of immortality is more present than ever before. I think there is something in the idea that the artwork becomes an almost immortal living organism. This project doesn’t finish when the exhibition finishes. First of all, it’s going to be a world tour, as we know already, but it’s also just going to somehow go on for ever.

EJ: The great opportunity with this exhibition is to rethink the point at which we bring the audience in. It’s not necessarily the final point because, as you say, that doesn’t exist any more when an artist makes a system rather than an artefact. So we thought a lot about how you bring an audience into the collective training of a model so they feel part of it and that they’re watching an evolutionary process, which exists in one form in exhibition, but also exists in many spaces at once and will continue to grow. What is this central moment that we’re inviting the viewers into and how do we make them feel that it’s going to continue? It also changes my role as a curator. I’m part of making this system and all the methods used to train it – my role is as much to develop and interface with the audience and the AI as it is to ensure that the people whose data was used to make the model have a strong governance over it.

HH: Something that we talk about a lot at the moment is this idea of the production-to-consumption pipeline being collapsed, that the very act of consumption can lead to the generation of media customised to your taste. We’re entering this phase where the production of media is endless and we have to contend with what it means to have infinite media, infinite images, infinite songs, something that is infinitely customisable. That could be alienating or it could be interesting. It could further entrench people in their own filter bubbles or it could create entirely new subcultures. I think everything’s on the table here, but it’s certainly a new paradigm.

That’s also why it’s important to wrap one’s head around this idea of a data set or any piece of media as a seed or a kernel that can just go off to create endless spawns in its own image and its own likeness. That’s why it’s so wonderful that we’re piloting this data trust model, because what can come out of that data is endless – it’s fascinating to find ways to try to govern that and work around that.

MD: One thing we’ve said for some time, which can also be applied to the infinite feed of social media – is that the more media becomes abundant, the more meaning or purpose becomes scarce. Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, talks about how, in ten years’ time, every pixel you’ll see on the internet will be AI-generated. That’s his thesis.

“We’re entering this phase where the production of media is endless and we have to contend with what it means to have infinite media, infinite images, infinite songs, something that is infinitely customisable ... It could further entrench people in their own filter bubbles or it could create entirely new subcultures” – Holly Herndon

In a scenario where media is produced faster than the speed of thought, you have to reconsider the role of any individual image or any individual song or gesture. When you first confront people with this idea, let’s say a musician or a painter, they’re shocked and in some cases a little scared because we’re used to valuing individual images or songs as scarce pieces of media. But as Holly mentioned earlier, we needn’t limit our thinking to consider the media alone to be the art, when in actuality art is a much more resilient and robust framework.

People from a more contemporary art tradition know this. They understand that artists develop their reputation on their practice. That may involve the accumulation of different media gestures over time, but fundamentally, the practice is the art in some ways, right? It’s the context. It’s why you do what you do. It’s trusting that an artist will come up with an observation or a gesture that may confound you, but it will be consistent with their practice. So when practices or protocols are condensed into software that can be executable, that for me is where it gets really exciting. That’s how you insert meaning in an infinite media context, and that’s also why it’s so important to get it right.

This idea of mind children, that we know that everything we do can be infinitely spawned in the future, gives us wonderful pause to be mindful and conscious of our actions and to rethink our practice, like, “OK, how would we act in a world of infinite media?”

I don’t think it’s controversial any more to suggest that images and sounds are going to be produced faster than the speed of thought in our lifetime. So what does an art world or an artist’s practice look like in those circumstances? I see it as a challenge to be more committed to what we value.

HH: Hans, you have this series where you have people write notes on paper. One of the last ones I wrote for you said, “It’s a little death but also a rebirth,” and it’s speaking exactly to this issue, because when I first started thinking, “Oh my goodness, the single image doesn’t matter any more or it doesn’t have the same weight any more, or the single audio file doesn’t carry the same weight because it’s infinite,” there was a little death. But then once I feel like I ingested that and came to terms with it, I realised the potential for it, and that’s also the beautiful rebirth that happens – but it’s an emotional rollercoaster to get there.

The Call will run at Serpentine North from 4 October 2024 to 2 February 2025.

Fashion direction: Katie Shillingford. Hair: Kosuke Ikeuchi at Shotview. Make-up: Kenny Campbell. Props: Tara Holmes at Laird and Good Company. Fashion assistant: Precious Greham. Pre and post-production: A New Plane. Technical director: Tom Wandrag. Producer: Róisín McVeigh. AI creative technologists: Alex Puliatti and Andrea Baioni. Special thanks to Eva Jäger

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale now. Order here.