Art historian, curator and writer Alayo Akinkugbe is behind the popular Instagram page A Black History of Art, which highlights overlooked Black artists, sitters, curators and thinkers, past and present. In her column for AnOthermag.com titled Black Gazes, Akinkugbe examines a spectrum of Black perspectives from across artistic disciplines and throughout art history, asking: how do Black artists see and respond to the world around them?

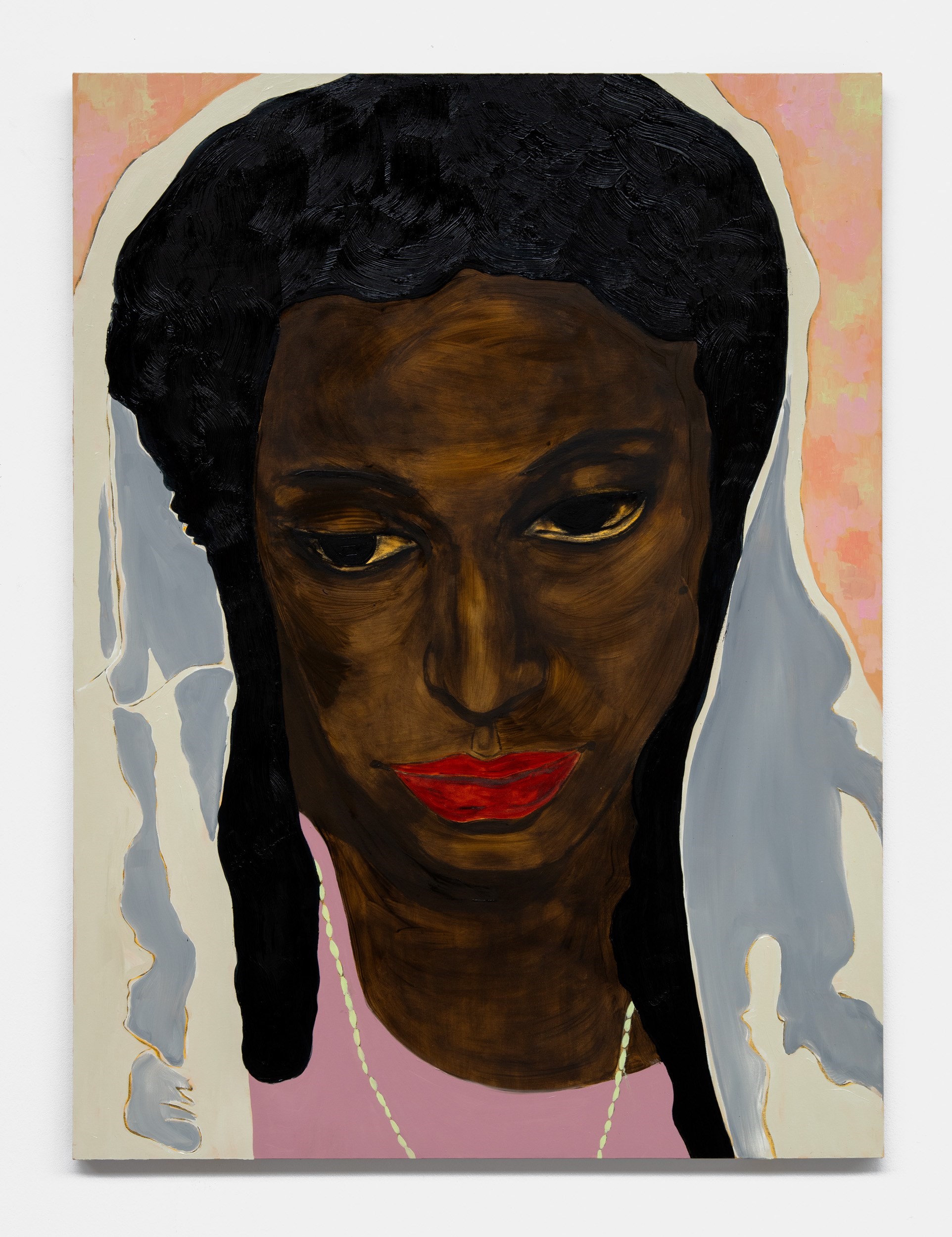

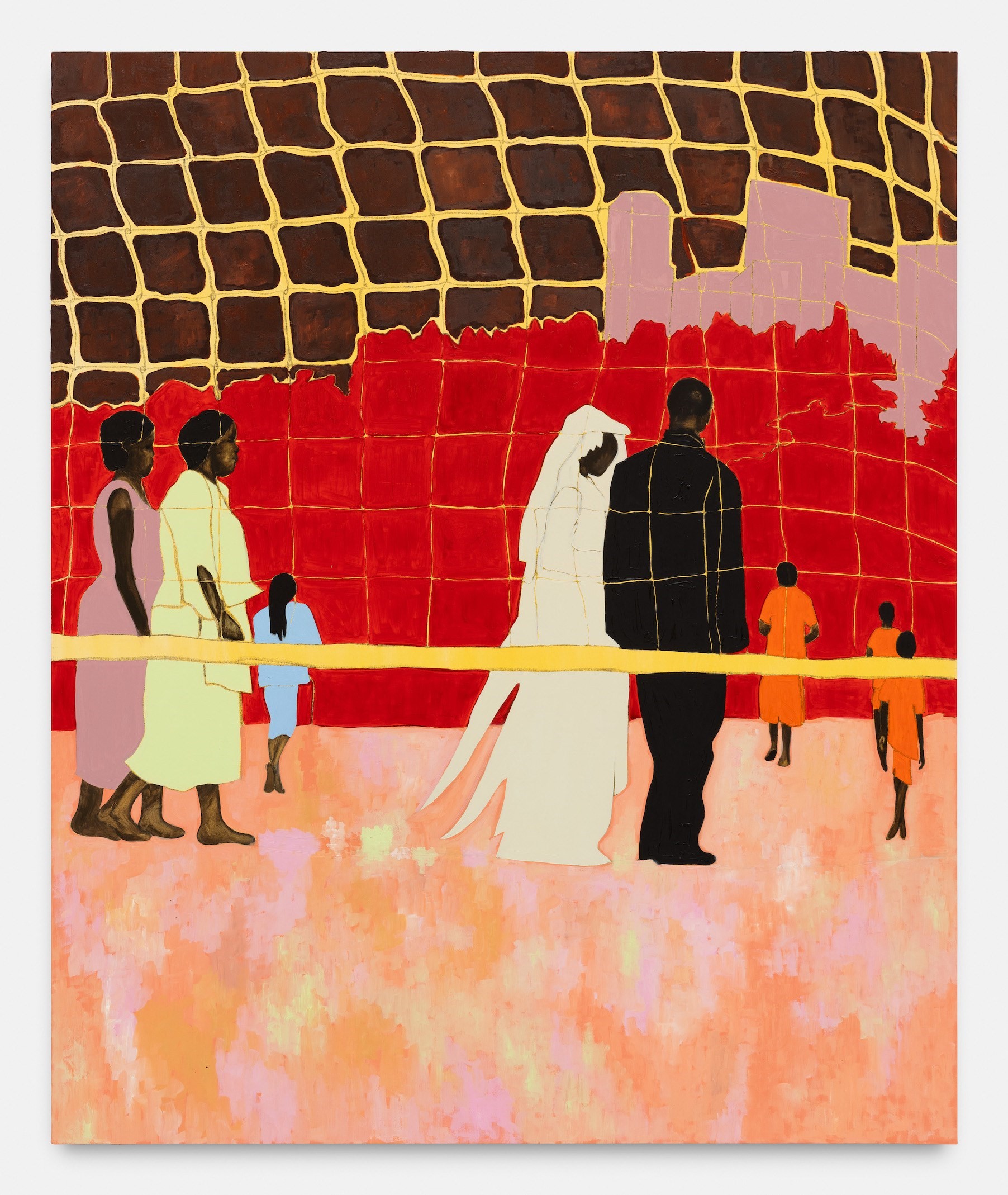

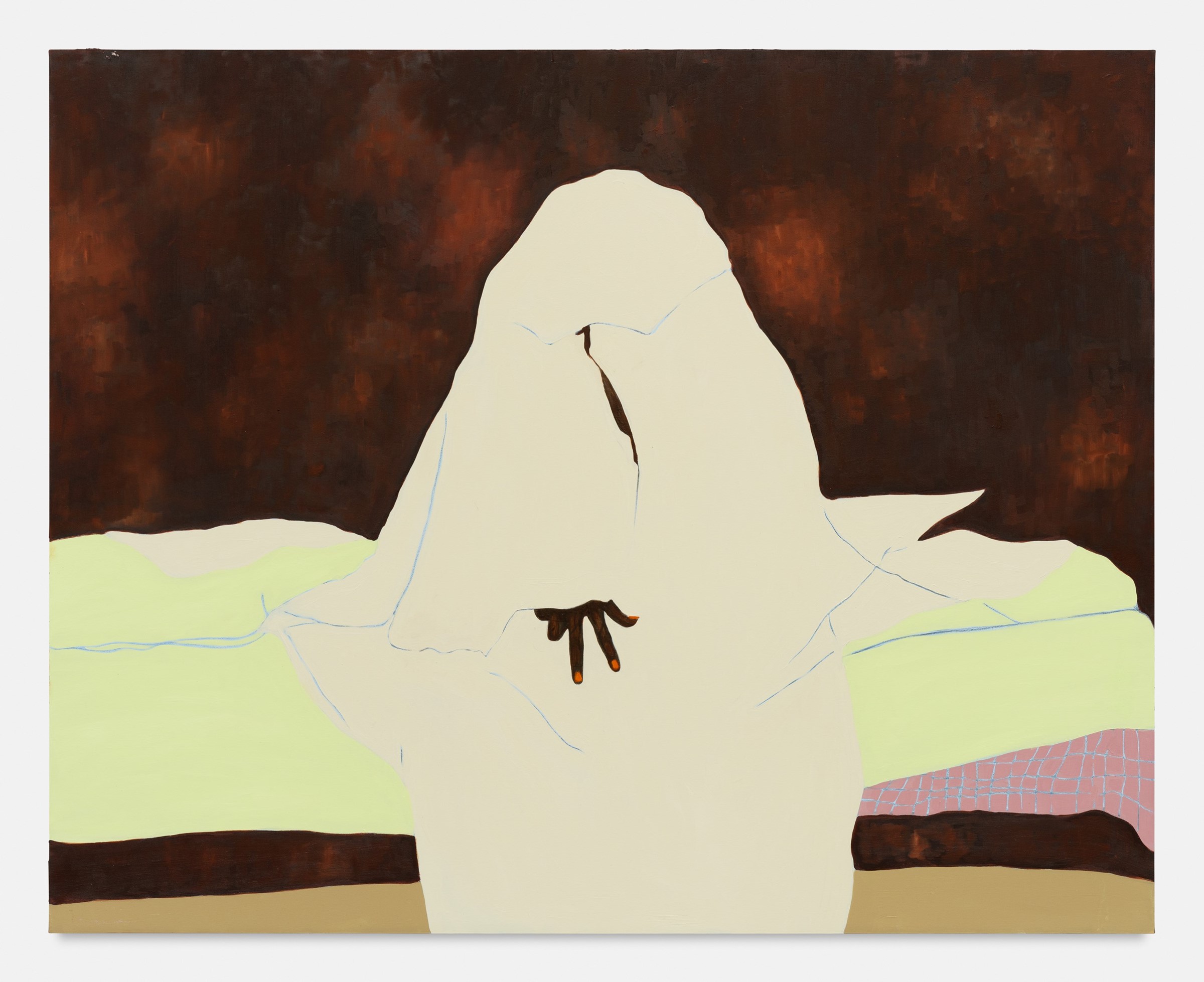

Cassi Namoda’s paintings depict imagined characters in rural southern African settings, assuming daily village life. Her work ranges from lively scenes of weddings and baptisms to intimate family portraits and close-ups of couples or weeping figures. They often have a dreamlike quality, with pastel-coloured skies and indistinct landscapes, and sometimes verge on the surreal, featuring whimsical hybrid figures and performing masquerades.

Namoda was born in Mozambique, and it is the sights and sounds of the country that inspire her paintings. She has, however, led a nomadic life, attending boarding school in West Africa and moving frequently throughout her career. Recently, she relocated from the Berkshires in rural Massachusetts to Biella, a city in northern Italy.

Her new exhibition, The Equator’s Forfeit, is influenced by her experiences prior to moving to Italy. In the year before she made these paintings, Namoda found herself at residencies in Ireland, Senegal and Connecticut, at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, where she became immersed in colour theory.

In the following conversation, Cassi Namoda reflects on her love of painting itself and Fauvism, the politics of marriage in African cultures and the constant sense of nostalgia for one’s homeland, experienced by those in the diaspora.

Alayo Akinkugbe: The title of your exhibition is The Equator’s Forfeit. Where does it come from?

Cassi Namoda: There’s a painting [which I made before] that’s called The Equator’s Forfeit. I like the notion of it because it maybe doesn’t [immediately] make sense, but it sounds poetic. I’m always thinking about diaspora and the African continent when I’m storytelling, and [about] the equatorial line. I thought, ‘What about the stories about those countries and those people that live amongst the imaginary equatorial line?’ I think there’s something that is very unifying between these countries. It could mean many things to many people, but if you break down what forfeit means, it is to be at a loss, to succumb, to quit, or to lay all your chips on the table.

AA: You recently moved from the US (the Berkshires) to Biella, and you’ve been nomadic throughout your career. How have your recent experiences of living in these different places impacted your approach to painting?

CN: I started these paintings a year ago. I [had been] in Ireland, Senegal and The Josef and Anni Albers residency in Connecticut. I started in Cork, Ireland, in a really isolated zone with a singular house on an edge of a cliff, which was very existential in its nature. Having that experience for a month and a half where my only friends were the blackbirds or the crows was a lonely thing.

Then I was in Senegal and it became a little bit more intimate, because I was nestled in village life, which is at the heart of [the stories] I enjoy telling in my work. I was observing these women who were fabulously beautiful, and the men and the children. This experience was the prelude to this body of work, because as soon as I arrived home, I was like, “Oh, it’s The Equator’s Forfeit.”

“Being in love is a very fleeting idea. The West has adapted union and marriage from some fairytale situation and in [many] African cultures it’s the opposite of that” – Cassi Namoda

AA: These paintings seem to be set in Mozambique, the country where you were born. Why does this setting inform your work so strongly?

CN: I think many African painters, certainly [those of the] past, look to have a sensory experience, something that we can relate to and that we feel in our daily life. Like women walking through a field, the chatter, the babies cooing, the sound of a busy road. I think – in a diasporic way – we’re nostalgic about those things.

AA: Painting is your primary medium. Why are you drawn to it?

CN: When I was in boarding school in West Africa, my history teacher (who was also a voodoo priestess) said some people are born with specific callings, and [they] don’t know why. I think the same thing. I’m meant to be here and my legacy is to tell stories and to do it through a visual sensory experience: through colour and through gesture. To me, painting just feels boundless and full of curiosity, and the ability to grow is there. That’s really intriguing to me because, in a human sense, that’s what life is all about.

AA: One painting in this exhibition re-imagines Gauguin’s When Will You Marry? Which artists of the past are you most influenced by?

CN: Painters of the Fauvism movement who were very interested in challenging their sensibility around color. Some painters went to the south of France and painted what they saw, but that wasn’t enough for artists like Gauguin. They wanted something “savage” – I mean that in a white male sense. For me, the irony is that [this idea] is something much more wrapped up in my DNA, so I’m taking agency over something that in some way wasn’t personified correctly [by these artists]. I take it and then I make it very relatable to us as African women. It’s a little bit tongue in cheek.

I think painting is haunting. So [paintings] come to you, and they will give you the answers if you let them. I like this idea of puzzle piecing; with [this painting] I was having conversations with my aunt and we were talking about marriage, and I was thinking about [what it means] to be an African daughter. Then, I ended up doing the Nikkah (Islamic Marriage), and then I realised, “Oh, these paintings are unfolding in my life.”

AA: Do the paintings in this body of work come together as one narrative?

CN: I wanted to show the mysticism, romance and challenge in traditional African cultures. Westerners come into my studio and see those paintings, and they’ve said, “I just don’t believe in arranged marriage,” or “couples should meet and marry because they’re in love with each other.” And I’ve said, “Well, being in love doesn’t always last.”

Being in love is a very fleeting idea. The West has adapted union and marriage from some fairytale situation and in [many] African cultures it’s the opposite of that. There are family bonds, there are practicalities, there are logistics, land and cattle – it’s a whole thing.

AA: What would you most like the audience to feel when they encounter this exhibition?

CN: I would like for the viewer to walk away enchanted, but also disenchanted. To have a sense that life is complex and living is work and that not everything is as simple as it seems, and that’s just like the human experience. It’s like walking away from a good movie; you can have a conversation. To me, that is the art of storytelling.

The Equator’s Forfeit by Cassi Namoda is on show at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels until 23 November 2024.