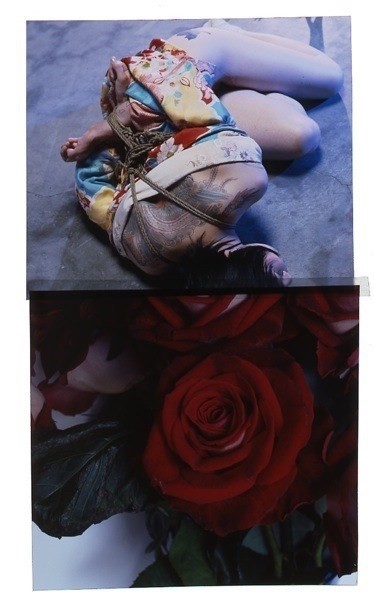

How do we learn what is shameful? Which urges are seen as natural, and which remain in the dark? In recent years, social media and its algorithms have played a powerful role in defining sexuality, claiming a host of images unfit for public consumption. This has had an especially significant impact on artists, many of whom explore sexuality in a nuanced manner that transcends the simplistic rights and wrongs of censorship technology. A new exhibition at SHOWstudio celebrates the unrestrained pleasure of sex as seen by artists. Shadow Ban brings emerging names such as Olivia Sterling, George Rouy and Oh De Laval together with established provocateurs Nobuyoshi Araki, Dinos Chapman and Tom of Finland.

“Culture is evolving into this highly censored medium and I don’t think that does justice to our imaginations,” Knight tells me. Originally, he says, the birth of the internet felt like a positive move away from galleries and publishers holding all the cards. Artists could now show their work online without purely commercial intentions. But this quickly gave way to a new form of gatekeeping, with authentic, creative expressions of sexuality leading to shadow bans.

“There are two things that really fall foul of censorship. One is politics, and the other is sexuality,” says Knight. He notes that the shadow ban, in which an account is withheld from search pages without warning, is particularly murky. “If, as an artist, you know what the parameters are, and Instagram is upfront about their censorship rules, you can choose not to put your work in that arena. But because it feels arbitrary, it’s hard to know when you are going to cross a particular moral or sexual boundary.”

While many of these arbitrary decisions happen on an automated level, their boundaries and behaviour are ultimately set by individuals. “We don’t know who is deciding this,” Knight considers. “There’s an idea that it’s just the algorithm, but somebody human is saying ‘this is not acceptable’. We should, in 2024, be an enlightened, sex-positive society, not one that is regressing into demonising sexuality. Most of us are sexual to some degree, so this leads most of us to think our actions are wrong.”

Some artists in the exhibition have had a very direct experience of censorship. One famous example is Harley Weir, who, in 2016, found her account wiped after sharing an image of a nude model with menstrual blood on her thighs. While Instagram eventually republished the photograph, the message that there was somehow something deeply wrong about menstruation was hard to shake. “It’s a natural, human thing so why should it not be seen?” Knight says, reflecting on how bodily functions such as menstruation and breastfeeding fall foul of sex censorship (his own image of a nude, pregnant Erin O’Connor was also taken down by the app). “It would be more than nice if the beauty in natural things could be seen for what they are, rather than grotesque,” Weir said at the time. Her photograph Egg, which is included in Shadow Ban, reflects a palpable sense of intimacy as her model rubs their cheek and lips across an exposed, semi blurred breast.

“Culture is evolving into this highly censored medium and I don’t think that does justice to our imaginations” – Nick Knight

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Peter Saville’s Bondage Bed speaks to unbridled sexuality without showing the human form. His clean, white sculpture is almost clinical, while suggesting the potential for playful bodily mess. Oh De Laval similarly evokes the thrilling possibility of eroticism; her painting Taste Lingers Even if Everything Else Fades Away features a luxurious chocolate being sensually stretched between a mouth and hand, and a toy breed of dog with a phallic protruding tongue. Emma Stern places her young, doll-like protagonist in a passionate embrace with a skeleton.

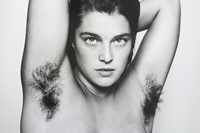

Some explore the line between art, clothing and fetish: Ray Caesar’s paintings are full of rubbery surfaces and stag-like headpieces, while Miles Greenberg’s almost nude figure hovers between the slick aesthetics of fashion photography and statuesque objecthood. Tom of Finland’s work accounts for a significant part of the show, which runs alongside the annual Tom of Finland Art & Culture Festival; his pieces present the male body in potent erotic form, with muscular buttocks and shiny leather clothing.

“The Tom of Finland Foundation came into being partly because a lot of young gay artists were being censored,” says Knight, highlighting the importance of the foundation since the Aids epidemic and the power of the late artist’s overt approach to gay sexual expression. “His craft is graphically beautiful, it’s not so far from Aubrey Beardsley. Of course, the work talks about a part of our sexuality which is misunderstood, badly represented and demonised.”

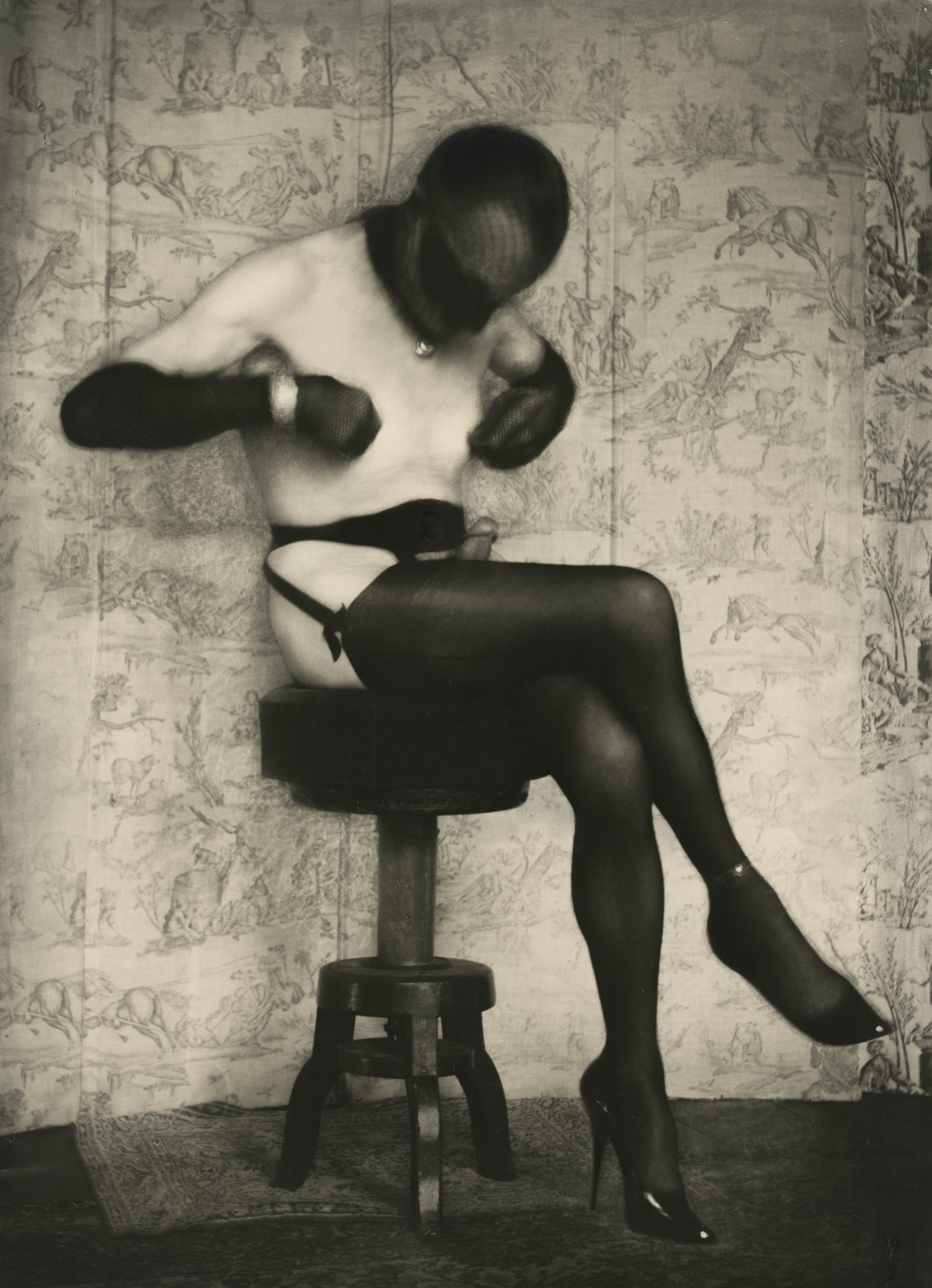

Pierre Molinier’s photographs are also featured in the show; working as a painter and photographer in the early 20th century, the artist embraced androgyny and was known to dress in his wife’s lingerie. His grainy black and white photographs celebrate a fetishistic view of sexuality, with black corsetry, suspenders, and facial masks. “Molinier’s personal behaviour was so out there and marginal that even the surrealists couldn’t countenance him,” says Knight of the work.

He highlights how important it is that unconventional artists such as this are embraced rather than pushed to the margins. “I would prefer a society that wasn’t judgmental, but that tried to understand. If you drive people into secrecy as the victim of society’s hate, that creates much more extreme behaviour. If we try to understand why people do what they do, we can have a much more grown-up discussion about sexuality, which is better for everybody.”

Shadow Ban is on show at SHOWstudio in London until 15 November 2024.