Penny Slinger's home is surrounded by the forests of Boulder Creek, California: a desolate place, consumed by mysticism and removed from reality. It stands on the top of a hill, next to a opulent fountain and beside a large blue stage that she built

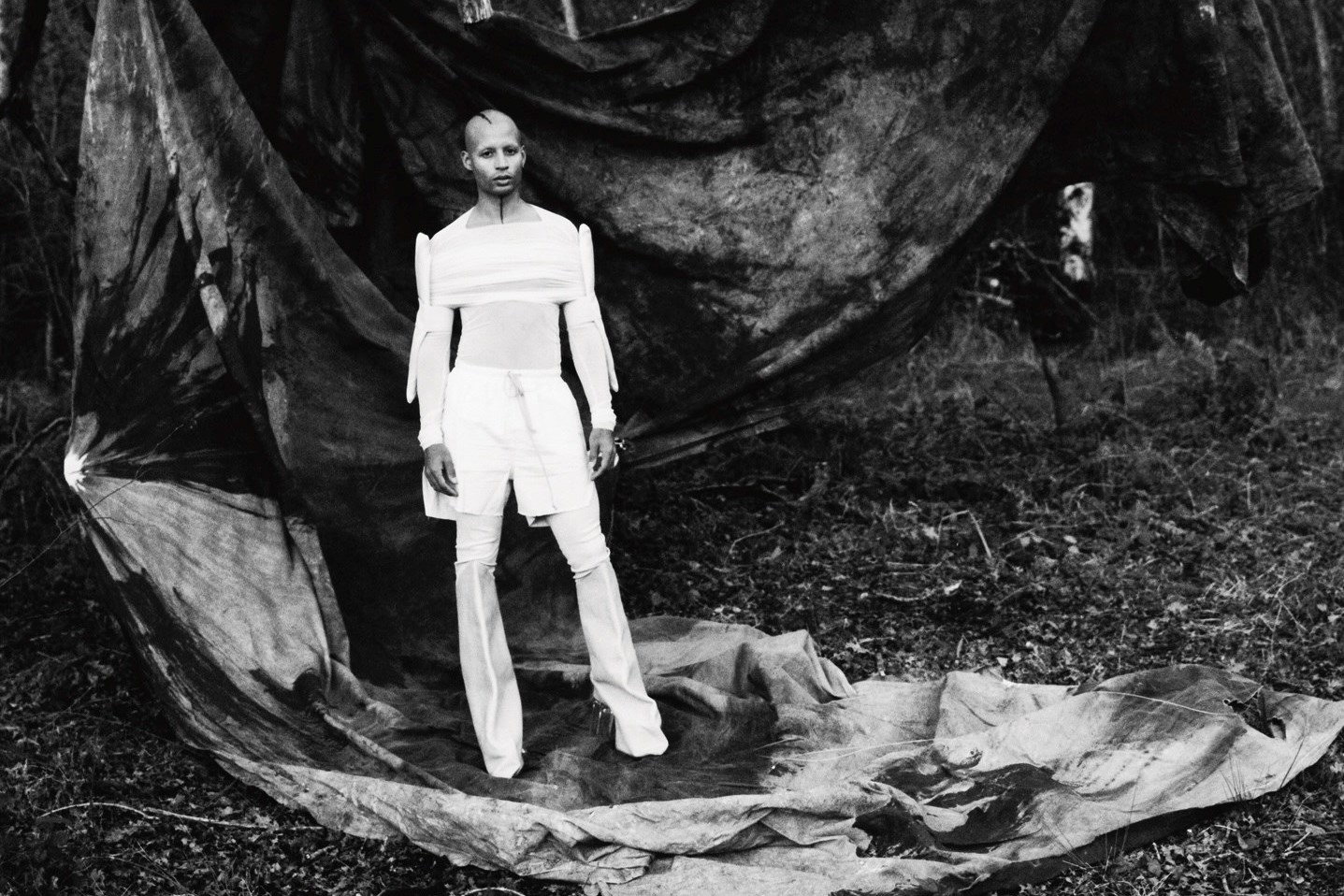

Penny Slinger's home is surrounded by the forests of Boulder Creek, California: a desolate place, consumed by mysticism and removed from reality. It stands on the top of a hill, next to a opulent fountain and beside a large blue stage that she built herself. It is covered with an unusual rock formation, the remainder of a midnight ritual performance. This same mysticism has dominated her work since the late 1960s, where she has taken herself on a surreal journey and used the simple technique of collage to craft her own seamless reality. Her studio is filled with old costumes, headpieces and masks, each object a reminder of her ability to surrender to the possible multiplications of the self, by taking on the role of both object and subject within highly charged scenes that she controls. Her most self-reflective body of work is her 1977 series An Exorcism, a seven year journey that was photographed inside the historic rooms of Lilford Hall and resulted in the publication of a book. She describes it as "a surreal romance in photo collage", and it is as much about herself as it is about the breakdown of her relationship with filmmaker Peter Whitehead, who introduced her to the building in 1970, with the intention of making a film together. Instead, Slinger transformed the internal surroundings of Lilford Hall into her own complex stage, capturing herself in the theatre of an obscure world. Linder Sterling was first introduced to Slinger's work as a teenager, after a friend of hers stole a copy of Slinger's book 50% The Visible Woman from Birmingham Library. There is a magnetic connection between both Sterling and Slinger's work, in which both artists transport the simple act of collage into a new contemporary language that is always motivated by a strong feminist perspective. The morning after their talk at The Whitechapel Gallery, AnOther spoke to the two women about love, the female psyche and re-editing their past, alongside rare unpublished works from Slingers's Exorcism series and a debut of her unseen 1969 silent film Mouths and Masks.

Linder, what first drew you to Penny's process?

LS: I think a lot of what Penny does is make maps of her own life. That cartography is psychological and sexual. It helped people like me see that there is a map and that someone was slightly ahead of me on this journey. Penny is a great cartographer not only of the female psyche, but of the human psyche. Those maps are very articulate and she has left them there forever. I also think it was Penny's use of text at the time. Her writing is astounding. For me it works homoeopathically. She just drops those words, they can be quite sparse at times, but they work on a really deep level. I think it was that mixture of text and collage. Living in such a remote village in the north, I hadn't seen an artist's book like 50% The Visible Woman. I was about seventeen. It was such an important moment for me.

"Living in such a remote village in the north, I hadn't seen an artist's book like 50% The Visible Woman. I was about seventeen. It was such an important moment for me."

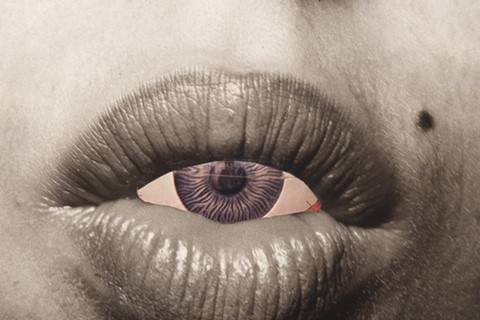

PS: I don't think there is much lineage for the feminine artist in particular. That is what galvanised me when I came into art, seeing that it is very much a man's world. There are very few outstanding female artists in the history of art – I just thought, we need this. That is what spurred me on to make that mark and take these tools that have been explored with surrealism, exploring the psyche, and making it particularly about the feminine. It was quite funny, yesterday during the talk, a critic asked me if the mouth on the first page of 50% The Visible Woman was Marilyn Monroe, but it is mine. Somehow, instead of having the glamour with it, you have something that can make you feel very uncomfortable and make you think again. Especially when you're using the same kind of imagery as advertising, but instead it is nothing to do with that. You have to shake up those perceptions, because we are not objects we are subjects. It is what we are trying to claim back. I think so much movement has happened since the 70s, but there is still a lot of movement that needs to happen.

LS: Returning to England on this trip, how much do you think things have changed? I mean there has been surface change, but…

PS: Well I think a lot has changed in a sense of what is available. When I first making work, it was unthinkable for a woman to show herself unclothed unless she was in a men's magazine. That's why I deliberately put some articles in men's magazines. I was there with my art, speaking my audacious words, claiming a place to say – I am not your object. I felt it was really important to do that. Now we have all this glut of pornography and erotica, but not a awful lot of it has really claimed that similar kind of space. In a way, it is still very generic. We have a lot of space for movement there. That has always been my struggle, to be a sexual person, a sensual person, a thinking person and a creative person. To be a mistress of my own destiny.

By using your own body as a tool in your work, do you ever feel a detachment from the self? Or the emergence of another self?

PS: This is something that I have meditated on. In that deliberate decision to make myself both subject and object, it gives you both a detachment and a involvement at the same time. I felt I could be much more ruthless with my own image than I would like to be with somebody else's. I can distance myself and see myself as this work of art. You can be both sides of the mirror. For me, it is a very powerful reflection and that gives you an extra diminution to work with.

LS: I also wonder if one is already experiencing that anyway, and after an attempt to communicate that, whether it is through being a woman in this culture or whether you have that split of being viewed as both object and subject, then the art making process is trying to make sense of that. I'm not sure which comes first. In this culture, one is experiencing that split all the time, and the trick of the artist is to use that. You can end up feeling quite divided and myself and Penny have discussed R.D. Laing's The Divided Self. I think if you're not in control and it remains unconscious as a woman it can be quite damaging. It is about playing with the multiplication of the self, to spin them out and really parade them.

"That has always been my struggle, to be a sexual person, a sensual person, a thinking person and a creative person. To be a mistress of my own destiny."

In the Exorcism series, the work is very much about relationships and the break down of your relationship with your partner at the time, Peter Whitehead.

PS: I think a lot of my work is about relationships, how we relate to ourselves and how we relate to others, particularly in terms of the dynamic of the sexes. That has been one of the main themes that has worked throughout my life and it has very much to do with the balance between the male and female energies. I have always felt that it is a balance of the male and female within and how that manifests in the outside world has always been a little bit of a struggle, especially if you are a strong woman. How you keep that strength and that integrity of who you are and in the same time have the room in your life to be able to relate to another human being in a way that is both satisfying and forfeiting. That challenge has been there all my life. Especially not wanting to be in the conventional line of things. I knew my children would be my art. I love creative partnerships, being able to collaborate and work with other people, but it is not always easy. In fact, in my relationship with Peter Whitehead, the filmmaker, we went off together to produce films together but it never manifested as a film. He went on to use a lot of the themes and ideas that we were working with, to make this film with Niki de Saint Phalle called Daddy (1973). That was his journey. I used all of the photographs that we shot in Lilford Hall that we were originally used to shoot a movie, but I don't even know what happened to that footage now, I can't find it. I used the set, to look at the dynamics that had happened between us and for my own self-reflection, but it didn't fulfil itself in a co-creation. My whole thrust for getting into Exorcism was really the break down of that relationship. I think it had a lot to do with who was in control. I thought we could both be, but it is always hard to do that. At the same time, I am at my absolute happiest when I am co-creating. It is not that isolated, artistic process.

Do you find it easier working with women?

PS: In a sense, I think society has pitched women against each other. I think we have been robbed of that ability to come together in a circle. For many years, I have been looking at that circle of the feminine and how we can all be complementary to each other, rather than competitive with each other. We would have a tremendous feminine power here. I think that is why we have been divided, because it is so perpetually powerful. If the women get their heads and hearts together, we could come into a new kind of resonance and understanding.

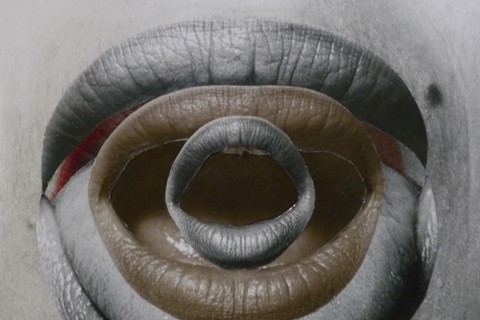

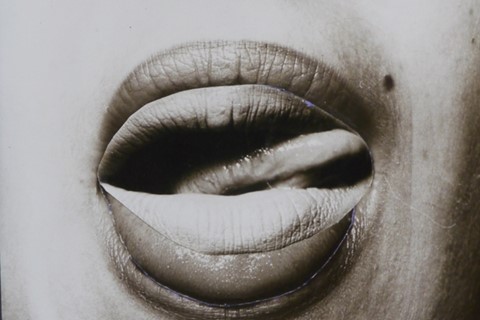

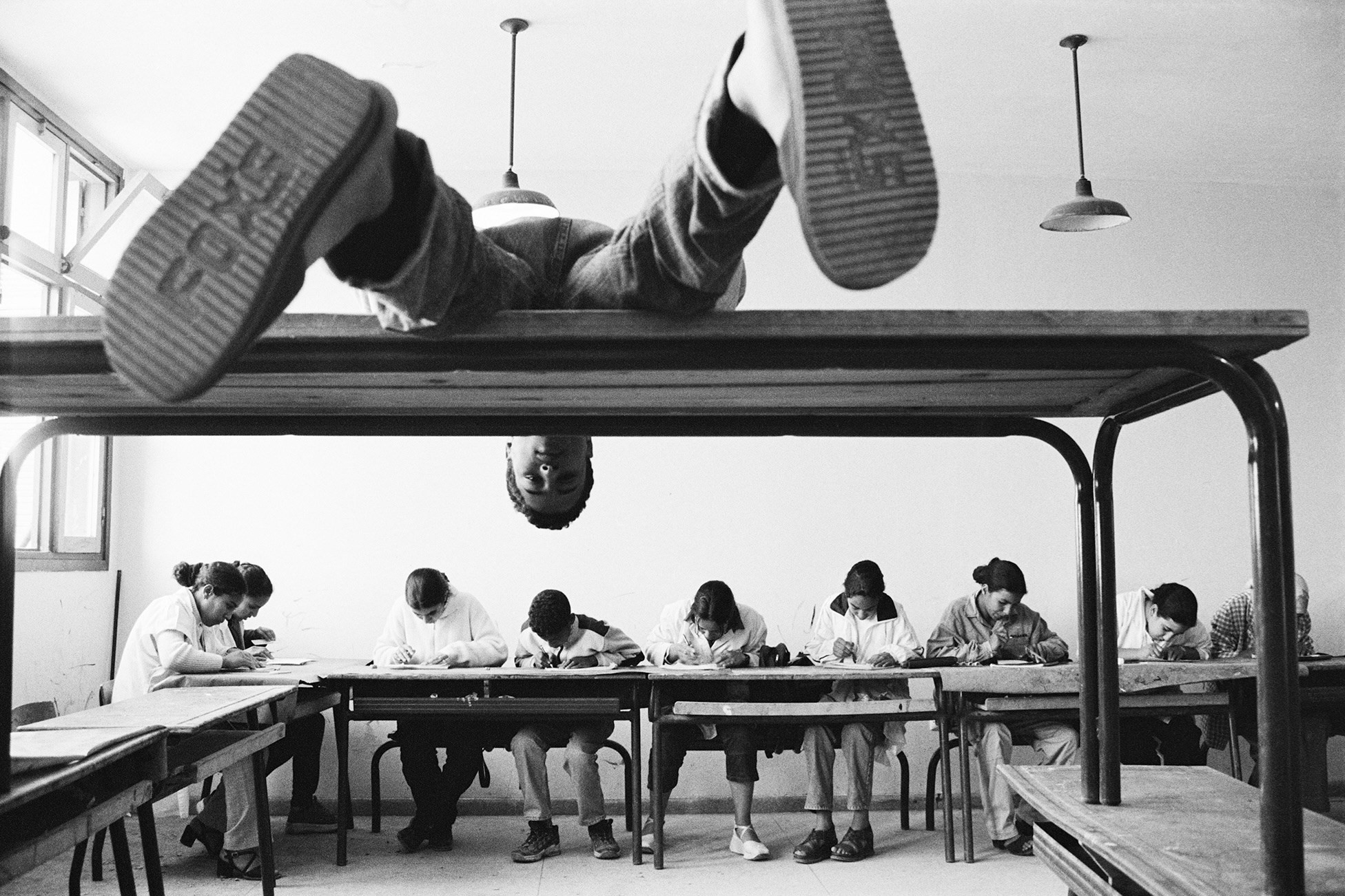

Penny Slinger, Mouths and Masks, 1969, © Penny Slinger 2012. All right reserved. Courtesy of the Artist and BROADWAY 1602, New York

Penny Slinger: Exorcism Revisited is at Broadway 1602, New York until November 30, and Penny Slinger: Hear What I Say is at The Riflemaker Gallery, London until October 3.

Text by Isabella Burley