We take a look at a new book surveying the whole span of Cornelia Parker's career

Renowned for her mass steamrolling of musical instruments and efforts to send meteorites back up into space, British artist Cornelia Parker has intrigued and engaged audiences for years with her hugely innovative pieces – predominantly sculptures and installations. Working with everyday objects, frequently reimagined via acts of destruction or alteration, Parker creates thought-provoking artworks that meditate on the frailty of our existence.

Last week Thames & Hudson published the first full survey of Parker's development – from her student years in the late 70s to the present day – complete with essays contextualising her work and an introduction by Yoko Ono. To celebrate, we present six of Parker's most arresting pieces alongside fascinating commentaries on each by the artist herself (as featured in the monograph).

(Above) "On visiting the Colt factory [in Hartford, Connecticut], I was amazed by the blank pieces of cast metal, which had in this first stage of manufacture already taken on the chilling, iconic shape of the gun. In one step further, a hole drilled, a surface filed, they would technically become firearms. I asked the foreman if I could possibly have a pair of guns at this early stage in the production, and if he could give them the same finish they'd get at the end of the process. Amazingly, he agreed, and they became Embryo Firearms, conflating the idea of birth and death in the same object."

"For a BBC documentary called Dates With an Artist (1997), I was asked to make a work for Rebecca Stephens, the first British woman to climb Mount Everest. In encyclopaedias, St Paul's is often placed beside Everest to show its scale. With this in mind, I asked Stephens to accompany me on a climb into the dome of the Cathedral. Unlike her, I have a terrible fear of heights. It was while on my hands and knees in the Whispering Gallery, trembling with fear, that inspiration struck. I noticed a thick layer of dust between the railings. I'd found a perfect material with which to make earplugs for a mountaineer, mute objects to wear at high altitude."

"When shopping in London's Brick Lane Market I came across this 1960s doll. He was the Charles Dickens character Oliver Twist, crying out because an invisible Fagin was tweaking his ear. Giving him a new reason for his new anguished expression, I used the guillotine that chopped off Marie Antoinette's head [which resides at Madame Tussaud's, London] to cut the doll in half. My little tweak of history caused a fictional character to share the same fate as a real queen."

"It was when making Mass in San Antonio, using the charcoaled remains of a white-congregation church struck by lightning, in 1997, that I first heard about the phenomenon of black-congregation churches destroyed by arson. I wanted to make a companion piece for Mass. It was several years later...[that] I read about a Baptist church that had been burned down in Kentucky by bikers who made a sport out of racial harrassment. The ageing black congregation had suffered years of intimidation at their hands...and then as a final blow, their church was torched. An exhibition at Yerba Buena Arts Centre in San Francisco gave me a unique chance to exhibit both works...as a diptych... The two churches seemed resurrected, as giant three-dimensional black charcoal drawings silhouetted against white walls."

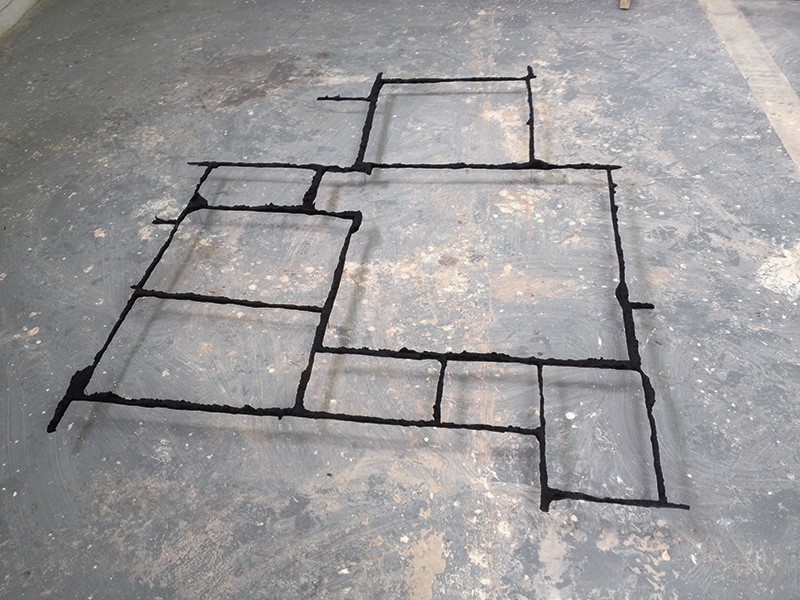

"Over the years of walking my daughter to her primary school near the Barbican in London, we would play Don't Step on the Cracks or Hopscotch. It rekindled an obsession with pavement cracks that had lain dormant since my own childhood. I identified with them in a near unhealthy way – wanting somehow to record their contours, occupy their territory. Something had to be done. I poured a liquid cold-cure rubber into some of the cracks. When it dried, I literally lifted up the geography of the city that had been mapped out in stone laid many years before. The captured rubber cracks were then cast in bronze, deifying the dirt, then placed on stainless-steel pins so that they seem to hover just above the floor, creating a kind of petrified line drawing."

"Travelling past Pentonville Prison daily on the way to the studio I observed workers busy repairing the cracks in the perimeter wall with white filler, making gestural patterns worthy of any Abstract Expressionist painter. I had been admiring their mark-making, meaning to return to record it with a good camera, but I saw that they were beginning to paint the walls with fresh Magnolia paint that would within minutes obliterate the prison abstracts. So I captured the cracks on my phone before they got painted out. A few hours later, on the same day, a murderer escaped from the prison after scaling the walls."

Cornelia Parker is published by Thames & Hudson and is available now. Additionally, an exhibition of Parker's new works, including In Pavement Cracks (City of London) and Prison Wall Abstracts: A Man Escaped, will open at Frith Street Gallery on June 7.

Text by Daisy Woodward